Interview: Tzu Cheng

"I simply came here to be an observer with an outsider's perspective."

Tzu Cheng, native of Taipei, Taiwan worked traditionally as a photojournalist before choosing to focus on artistic pursuits. His new work focuses on the delicate balance between the local and foreign. I’m a big fan of Tzu Cheng’s work Sadako and the Weird Kingdom.

Invited Tzu Cheng to share some notes on his work.

Q: Could you start with a brief thematic introduction to your work?

My works mainly focus on the foreignness under the American texture.

Q: Tell us a little about your background?

I was born and raised in Taipei, Taiwan. I am now thirty-three years old. I moved to the US for grad school in August of 2005. Prior to the move, I was a photographer for newspapers and magazines in Taiwan.

Q: How did you get into photography?

When I had to pick a major during my freshman year of college I chose to be a photographer. It seemed to me that a photographer has a good amount of independence, as opposed to something in the film industry, which I was also interested in. When I was hired as a photographer by a magazine in 2001, I felt the confirmation of photography as my lifelong career.

Q: How do you decide on locations & subjects?

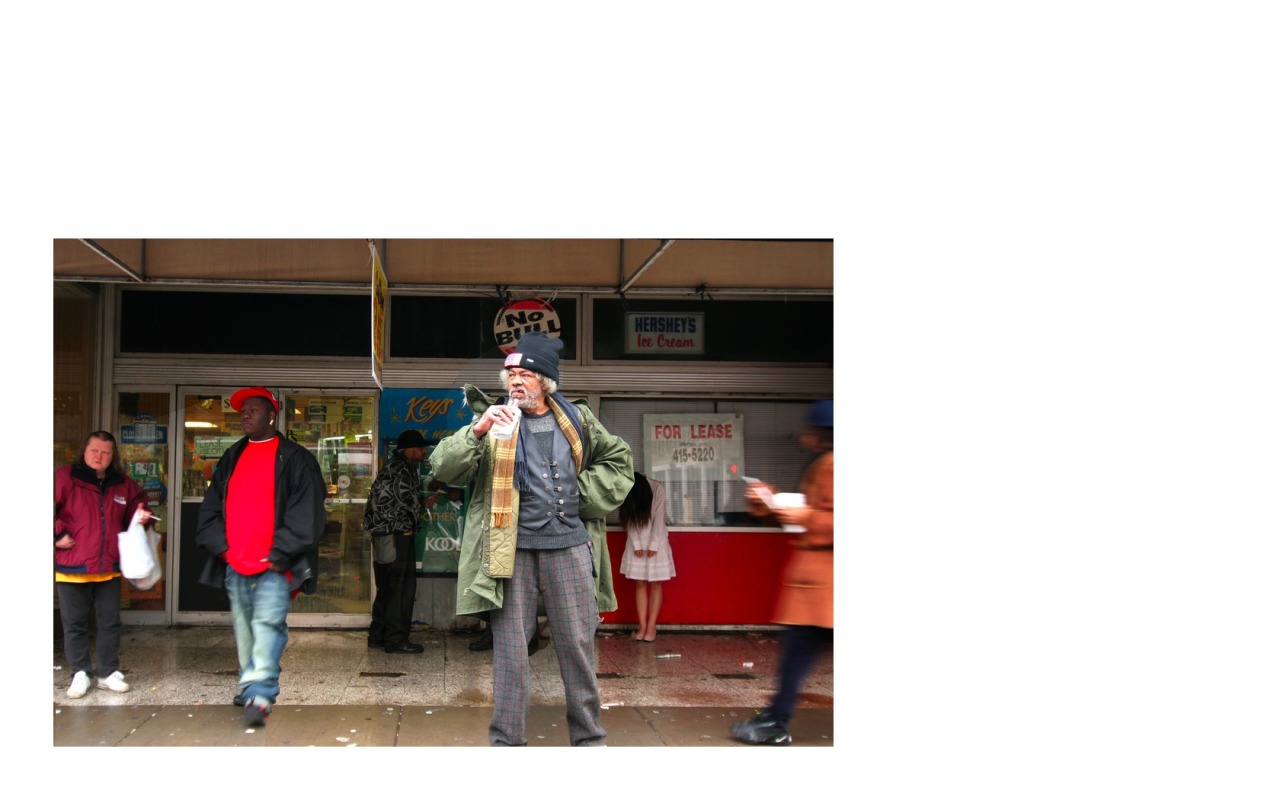

Most of my work was made during road trips, often near inter-state highways. I usually pull over, park, and start walking around to scout for locations and wait for the right subject to appear.

Q: I’m a big of your collection “Sadako’s Trip”. Tell us a little more about this project?

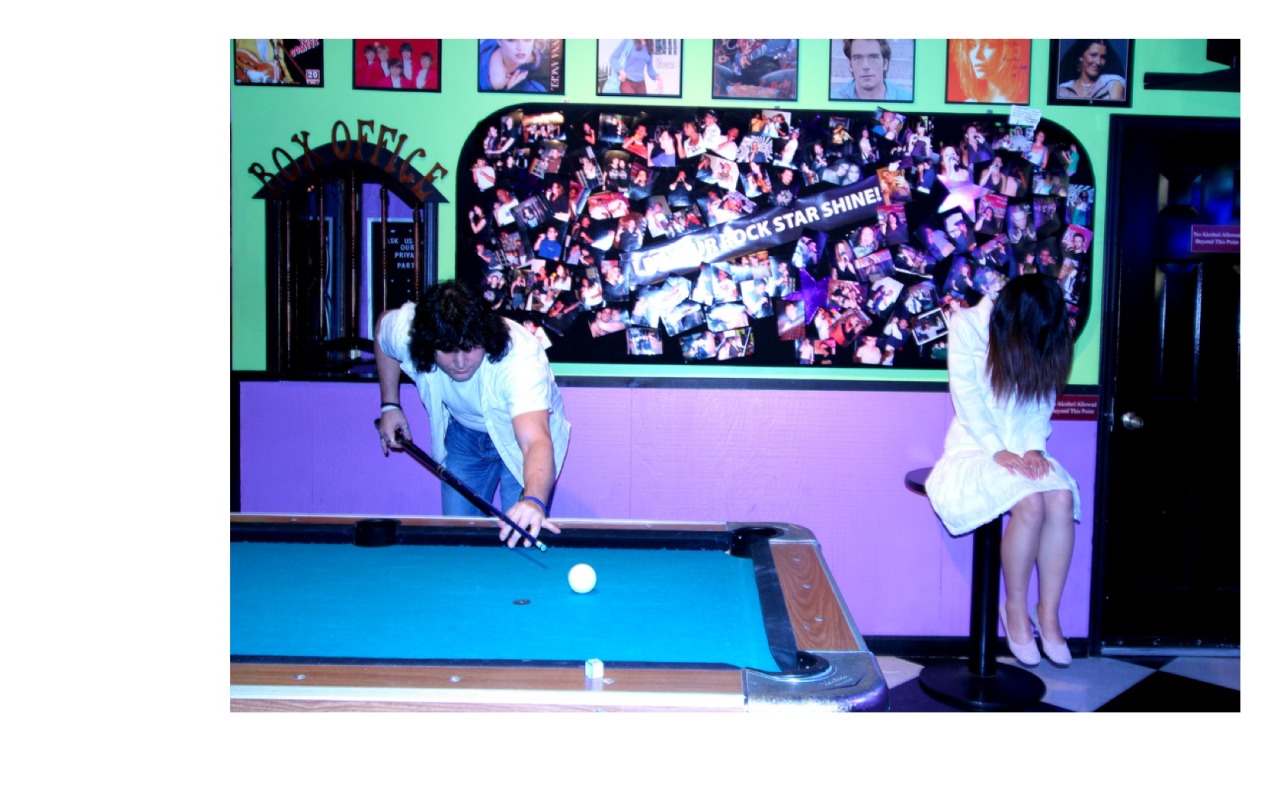

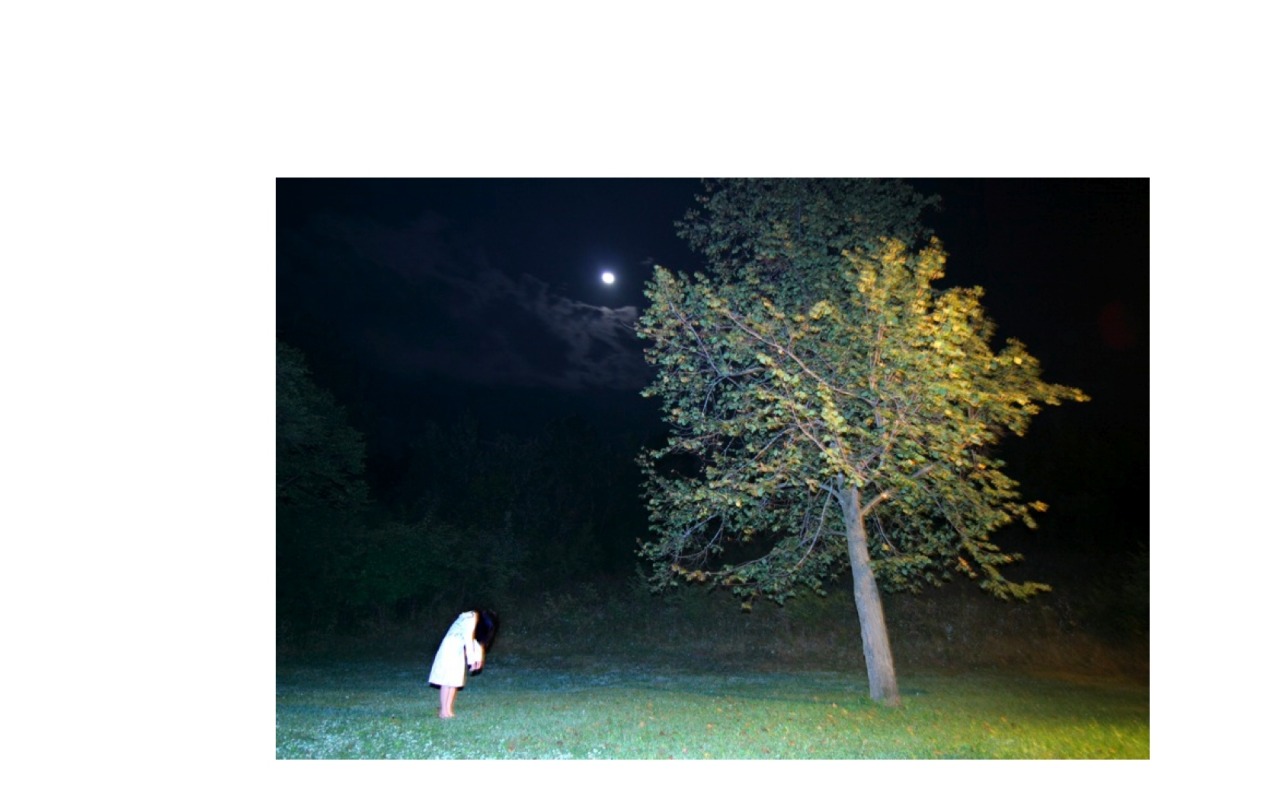

Sadako is the ghost figure of the classic J-horror(“Japanese Horror”) movie “Ringu” (1998). Before the “Ringu”, the skinny hair dangling figure had already haunted Asians for centuries. The whole project originated from the idea of the ghost image, which had also been a hot topic in numerous TV shows and publications for almost two decade in Taiwan, Japan and Korea.

For Sadako’s Trip, the relationship between the ghost figure and the innocent subjects is a potentially interesting metaphor for the relationship between foreigners and this country. In American society, foreignness can become a formality, the line between citizens and foreigners are blurred and hard to recognize.

Q: I couldn’t help but laugh with the reference and some of the humor the work has - were you intending it to have this humor - this subtle dark “Where’s Waldo characteristic?”

Not until a recent critique did I learn the meaning of “Where’s Waldo?” The visual arrangement is derivative of the pattern of the ghost image in which the paranormal often appears in an obscure spot within the image, which may be hard to recognize at first glance. The visibility of the ghost indicates one’s vulnerability within the context of the environment. It is a tactic for me to invite the audience to scrutinize the image, focusing on the bizarre landscape and interesting individuals.

Q: As a foreigner in the United States - do you think that maybe you in a way are “Sadako?” - Do you feel displaced in the “Weird Kingdom” or America as you call the country?

I came to the States first in 2005 when I was thirty. To adjust to the new environment and language, I had to go through the process like we all did as kids, learning how to socialize and build up the knowledge base of the larger environment. I was handicapped in a way. I used to be very vocal back in Taiwan, but here, I have to conceal that part of me and become reserved. In other words, I was forced to shut up and it made me feel like a ghost.

I don’t feel displaced because I was not meant to be an American to begin with. That is how I mentally prepared myself. As a visual artist, I simply came here to be an observer with an outsider’s perspective.

Q. Do you feel that your identity changes when you lift the camera to your eye? Do you act differently?

A camera at hand seems to legitimize the act of approaching someone you don’t know. And it feels even more so to photograph in a foreign land. (I think I would stop here.)

Q: What sort of equipment and software do you use?

I used a Cannon 20D in the early stages of the project, inherited from my photojournalism days in which I felt more comfortable with a digital, mobile and smaller format camera. I am now using a Pentax 67, a medium format film camera.

Q: Would you give a brief walk through your work flow?

Seek consistent lighting conditions, I usually photograph in the morning before ten or an or two before evening. I am shooting mostly film now. After processing and scanning the negative, I adjust the image and proof it via the computer. I then produce files with different sizes of the same image for archival, web and print purposes.

Q: Is your work political, anthropological, commercial, artist? What is your goal in your core work?

I am a combination of those types except for the commercial part. As a commercial photographer, you need the capability of reading peoples’ minds. Your client, a paid customer, might not necessarily appreciate what you are, the message you want to put across as a visual artist.

I find myself fascinated by the idea of using photography to define a bigger context of a city or country. On the other hand, despite the fact that my work can be categorized geographically, I would like it to come across as something that everyone in part, can relate to.

Q: Who are some of your mentors, role models, and aspirations? Which photographers have influenced you most?

I photograph people on the street and have looked at the work of photographers in that realm- Robert Frank, Steven Shore, and William Eggleston.

I admire the work of Martin Parr. He confronts and flashes his subject head on without hesitation. He comes up with a vivid definition of the location and the subject. There are qualities of street photography but along with it his mastering of calculated precision. Those are all tools and traits I would like to put in my pocket, at my disposal.

Q: What are your thoughts on commercial, advertising related work?

The one thing that separates art photography from commercial photography and photojournalism is that as an artist you need to have a statement, a viewpoint of your own. When it comes to commercial photography, there is always something you have to sell for your client. The assignment has already been defined before it’s been made. In this perspective, the challenge of commercial photography would be more straightforward, though definitely not easier, as oppose to other types of photography.

Q: What is your relationship with the poses individuals? Are they strangers, models? Aside from Sadako - you mainly take pictures of strangers - is this on purpose?

Most of them are strangers, people I encounter on the street. I keep my eyes these people and think about all the possibilities of posing them. I always bother my subjects as much as possible. For that I am grateful to all the strangers that I’ve met along the way for their willingness to spare some of their precious time to help me.

Q: Is your work available for sale and if so let us know for our readers?

People are always as much welcome to give me response with their thoughts as to buy my work, though I actually don’t price tag my pieces at this moment.

My work is available for sale, please contact me at autumniac@gmail.com or drop a line to let me know what you think!

Thank you.

More @ http://www.liutzucheng.com/