Postcard: Architect Fernando Castillo Velasco

Architectural Evolution: 'Building For' to 'Building With'"

My sister resides in a unique private housing development in Santiago, Chile, designed by the renowned Chilean architect Fernando Castillo Velasco (1918-2013).

The intimate enclave consists of 15 homes each with their own layout and form but sharing harmoniously common elements including parking, a swimming pool, lush gardens and a design vocabulary in building materials and overall compositions. The development is one of many he designed over years in the La Reina district of Santiago.

Interior of La Reina Community Development / Castillo Velasco Chile

The project skillfully integrates individualized zig-zag patterns in the floor plans to inject a sense of novelty and adopts a formal design language that beautifully marries brick, cement, nature, and glass.

Photo: Interior of development in La Reina, Santiago / Castillo Velasco Chile

The project highlights Velasco’s later career goals of placing structures to minimally disrupt the surrounding natural landscape, including trees, rocks, and streams. Each visit to this development offers me fresh perspectives, fostering a sense of reflection and tranquility. It's not just a peaceful retreat; its a tightly-knit community seamlessly distant yet connected to the larger bustling city life outside. I’m inspired by how he is able to seclude intimacy and privacy among the development but still provide opportunity for tightness and closeness in community.

I wanted to bring attention to some Iessons I gleaned from Velasco's architectural approach which I think is relatively unknown outside Chile. I'll explore his career trajectory, highlighting a significant shift from his early centralized, utopian designs to a more fluid, individualized, and participatory style of architecture.

This evolution from 'building for' to 'building with' is a testament to Velasco's adaptability and vision, aspects of his work that I deeply admire and also reflects my own realization towards a more looser approach to architectural planning and design and a my owner personal disenchantment with centralized design.

Photo: La Reina, Santiago / Castillo Velasco Chile

A quick summary of his biography:

Fernando Castillo Velasco’s career was a tapestry of varied, yet interconnected roles. After graduating from the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, he co-founded the architecture firm Bresciani Valdés Castillo Huidobro (BVCH), where he worked from 1947 to 1966. Parallel to his architectural practice, Velasco also ventured into public service. He served as the three time mayor of La Reina (1966-1967, 1992-1993, and 1996-2004) and took on the role of the first lay rector in the history of his alma mater’s Department of Architecture from 1967 to 1973. His opposition to the military dictatorship marked another significant chapter in his life. He lived in exile from 1974 to 1978 and continued his activism in architecture upon returning to Chile. Velasco's leadership extended to being the governor of the Metropolitan Region in 1994 and co-founding ARCIS University.

In 1983, his contributions to architecture were recognized with the prestigious Chilean National Architecture Prize. Velasco continued to lecture, design, and advocate for community developments until his passing in 2013.

Velasco's approach resisted the trend of specialization and emphasized the importance of moral and ethical considerations in design.

I want to highlight the apparent contrast in his large-scale ('macro') and smaller-scale ('micro') projects. This examination will reveal the cohesive nature of his work and draw valuable lessons for a diverse audience, including residents, tenants, developers, and architects.

Unidad Vecinal Portales

Image: Casiopea, PUC, Tesis de Doctorado Humberto Bonomo

Fernando Castillo Velasco's early career began with a pivotal project: Villa Portales, or Unidad Vecinal Portales (UVP). Co-designed in 1950 by Carlos Bresciani, Héctor Valdés, Carlos García Huidobro, and Velasco himself, UVP marked a transformative moment in Chilean and Latin American architecture (a monumental shift to large scale modernism and public housing).

Situated in Estación Central, this at the time innovative housing complex comprises of 1,860 homes spread across 19 blocks on 31 hectares. It features wide corridors designed for pedestrians, bicycles and motorcycles, blending art and architecture, featuring Ricardo Irarrázabal's concrete bas-reliefs. UVP was envisioned as a model of dignified living, with ample green spaces and proximity to workplaces, responding directly to the challenges of urban migration and population growth. The project replaced centralized plazas with large corridors that the architects envisioned would serve as community spaces.

Image: Casiopea, PUC, Tesis de Doctorado Humberto Bonomo

However, UVP's ambitious design faced criticism and revealed complexities through the reality of use. In a 2013 video interview with Arch Daily (4), Velasco notes that Residents described their experience as living in both 'paradise and hell,' a sentiment that reflects the project's dual nature. Velasco himself acknowledged that UVP, while a shift towards modernist architecture, misjudged the project's scale, making it a mixed success at best.

Screen Capture from Video / Fernando Lavanderos

One of Velasco's key realizations was the difficulty in fostering a sense of successful community within such a large-scale project. Initially, the design, influenced by Clarence Perry’s Neighbourhood Unit concept, aimed to create humanized living spaces through pedestrian systems and communal areas. However, these spaces, particularly the expansive 'plazas' or long corridors, proved impractical and even isolating, failing to connect the community as envisioned. The sheer size of the population, around twelve thousand people, and the issues inherent in large-scale living posed significant challenges.

UVP Photo from hiddenarchitecture.net

Moreover, while the project intended to integrate with surrounding neighborhoods and share public spaces, this goal was not fully realized, impacting the social and community-oriented objectives. These reflections underscore the complexities and challenges of executing large-scale urban housing projects. Velasco’s experiences with UVP informed his later work, highlighting the often stark contrast between the initial architectural vision and the realities of daily life in such expansive living spaces. Also noted in the 2013 Arch Daily interview(4) Velasco notes his believe that the development filed to maintain spaces due to the lack of private ownership and stewardship by residents.

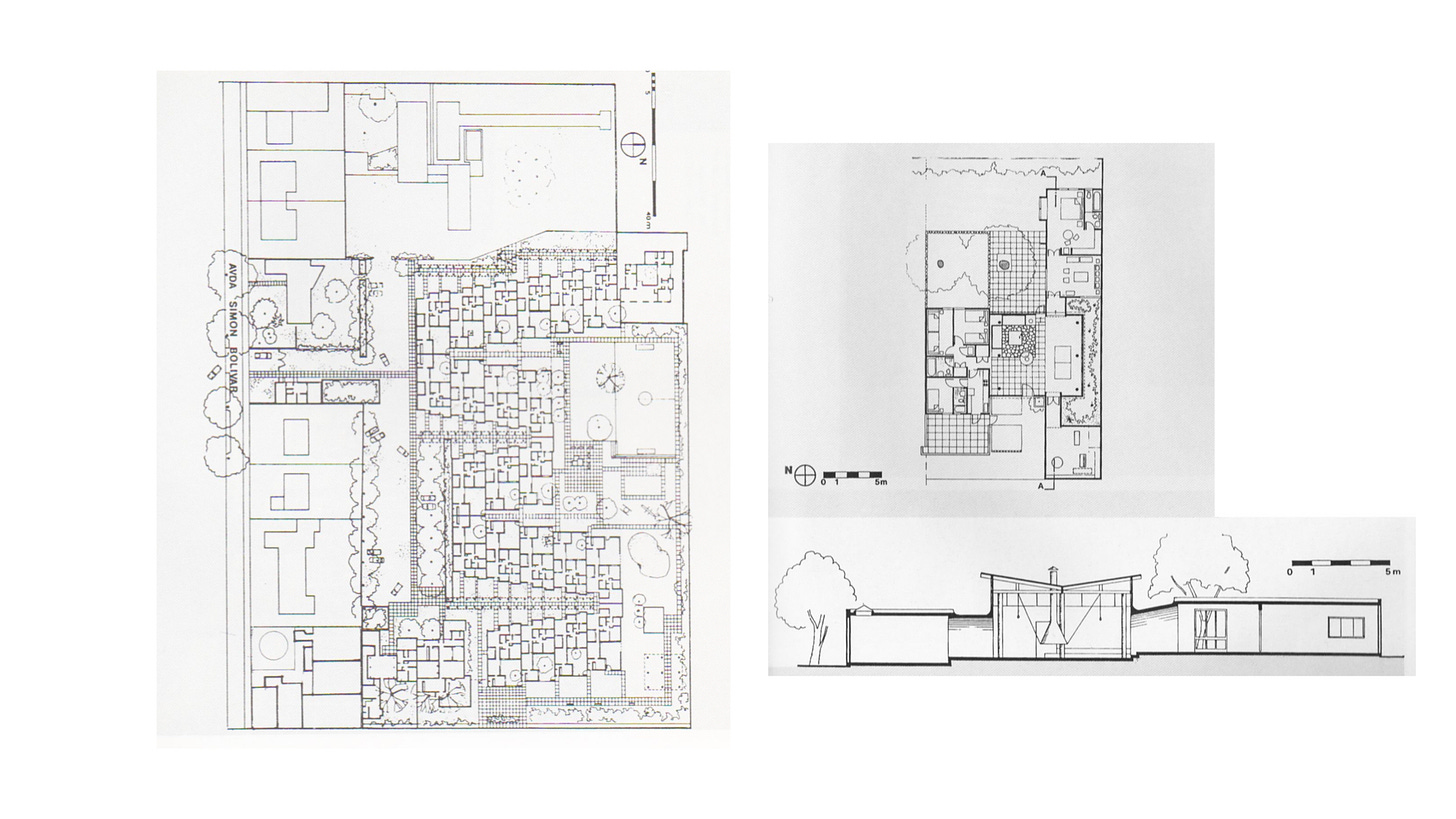

Quinta Michita

Photo: Humberto Eliash / Architectuul

It appears that Fernando Castillo Velasco's architectural journey took a pivotal turn after his experience with Unidad Vecinal Portales (UVP). In 1973, he designed Quinta Michita, a project that reflects a significant shift towards smaller-scale, community-centric developments. This project was a marked departure from the shortcomings observed in UVP, focusing on building a more intimate, human-scale community. Quinta Michita is distinguished by its collection of 25 one-story, zigzag dwellings, each designed with a focus on the collective aesthetic of the complex rather than individual distinctiveness.

Layout: Humberto Eliash / Architectuul

Over the years, Quinta Michita has garnered increasing popularity and success, a testament to its enduring design principles. The growth of vegetation and residents' personal modifications have contributed to this. Unlike the larger-scale UVP, Quinta Michita’s design allows for individual ownership, which has helped to address some of the maintenance and management challenges that were prevalent in the larger project. This approach might have have contributed to an increase in the value and desirability of these units and success later in his La Reina projects.

Photo: Humberto Eliash / Architectuul

The project's emphasis on sustainable community living is evident in how the dwellings have become more integrated with the natural environment over time. This harmonious blend with nature, coupled with the benefits of individual ownership, has made Quinta Michita a model for community-oriented architecture in the region, showcasing Velasco's ability to adapt and learn from his earlier architectural endeavors. The project still however seemed to mark its aesthetics and layout in a centralized rigidness as layouts are repeated and structure placed on an artificial grid without consideration of preexisting elements . Later projects will reveal Velasco’s shift towards loosening of his control over design and towards a philosophy of ‘building with’ and ‘not for’.

Community La Palmas

Exterior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Castillo Velasco

In the 1980s, Fernando Castillo Velasco further honed his architectural vision with the community developments in La Reina, one of which is home to my sister home.

These developments showcased his evolving approach: homes were individually laid out in a seemingly spontaneous manner, yet harmoniously integrated with the surrounding natural elements like trees, boulders, and streams. This design strategy aimed to preserve these natural features rather than displace them, striking a balance between catering to unique personal preferences and maintaining an overall sense of novelty and diversity. This is a major contrast to the rigidness of his earlier architecture.

Interior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Castillo Velasco

My sister’s experiences living in one of Velasco’s communities shed light on the practical benefits of this approach. Residents enjoy the privacy afforded by their distinct homes, yet they share common design elements that create a cohesive aesthetic. The homeowner association (HOA) operates on democratic principles, granting homeowners the flexibility to modify within their units while respecting communal spaces. This system has led to minimal conflict among residents, illustrating the effectiveness of Velasco's design in fostering community harmony.

This contrast becomes even more apparent when comparing my sister’s smaller development to larger projects like the earlier mentioned UVP. While fostering community cohesion is achievable in developments with 15 or 25 houses, the same becomes exponentially challenging in larger complexes with over a thousand units. This disparity highlights the practical limitations of large-scale developments in sustaining a tight-knit community.

Interior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Castillo Velasco

Personally as a developer Velasco’s work exemplifies how architectural design can significantly influence community dynamics. It underscores the importance of balancing individuality with communal harmony and demonstrates how home ownership can serve as a personal incentive for contributing to the collective well-being of a housing development.

Velasco’s journey as an architect also reflects a gradual decentralization in his design process, moving away from larger, centralized projects to more personalized and community-focused developments.

A further shift to participatory architecture

Velasco's architectural approach evolved significantly over time, moving from a focus on centralization and large-scale projects to embracing smaller, more personal designs. This transition also saw Velasco loosen his grip on the stringent control and dictation of his design language.

In an interview with ArQ(1), a prominent Chilean architecture magazine, Velasco reflected on this transformation. He questioned his earlier meticulousness, asking,

'Why did I do it this way? Why did I care so much about the detail? Why did we have to draw every wall, in elevation the brick was vertical, horizontally, then it was diagonal...?'

Interior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Carolina Katz + Paula Nuñez

These introspections led him to a more relaxed approach to the details in his designs. He embraced what he termed a 'how-to' culture, which encouraged continuous invention and novel ways of arranging bricks. Initially, he hadn’t seen much significance in this approach, but over time, he found it both intriguing and curious.

This shift in perspective allowed for more freedom in construction as well. Workers began arranging bricks in various orientations – vertically, horizontally, or diagonally. Velasco recognized that this flexibility reflected his belief that the essence of architecture resides within every individual, inherently marking each person individual nature as a fundamental builder. He also observed that involving residents and builders in the projects fostered a sense of pride, community, and ownership.

Interior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Carolina Katz + Paula Nuñez

Velasco's philosophical shift wasn't limited to his architectural practice. As the Mayor of La Reina, he extended this inclusive and participatory philosophy to his administrative and planning duties, further demonstrating his commitment to community engagement and empowerment.

Interior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Castillo Velasco

Awareness of Societal Role

In an interview with Ciper Chile (2), Castillo Velasco notes how his later architectural philosophy became anchored in the principle of 'doing with, not for'. With Ciper he notes that this view became particularly evident during his tenure as the Director of the School of Architecture at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Velasco was dedicated to expanding the horizons of his students, emphasizing the importance of a broad worldview. He notes that he advocated for an interdisciplinary approach to architecture, encouraging collaboration between different departments. His belief was that an architect's role transcends mere building design; an architect should also be a communicator, a connector of context and interests, bridging various fields and ideas.

This philosophy culminated in a powerful message he imparted to his students, emphasizing individuality and critical thinking:

'I send a message to my students that they should not submit to trends, that they should not submit to the great milestones of architecture.'

Fernando Castillo Velasco's influence extends far beyond traditional architecture. He inspired architects to think independently and break free from conventional norms, emphasizing the creation of unique architectural identities. This reflects not only his commitment to nurturing innovative thinkers but also his own ability to self-reflect and adapt. His diverse roles as an architect, public servant, and educator likely contributed to his design success.

Interior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago Chile / Photo: Carolina Katz + Paula Nuñez

From the serene courtyard of my sister's home, Velasco's architectural philosophy resonates clearly. His work transcends physical structures, offering spaces that balance inner peace and community with personalization. Velasco’s shift from 'building for' to 'building with' revolutionized his approach and profoundly impacted the communities involved. His legacy lies not just in the physical buildings he designed but in the human experiences and societal connections they foster. Velasco's life and work remind us that great architecture is about enriching the human condition, underscoring the need for adaptable, humane, and responsive design practices for generations to come.

A table summarizing my analysis of Velasco’s shift from building “for” to building “with”:

Exterior of Castillo Velasco home in La Reina, Santiago, Chile

References

- DÍAZ, Francisco; BERTOLOTTO, Hugo. “Fernando Castillo Velasco: una arquitectura de resistencia” ARQ (Santiago) no.105 Santiago ago. 2020 ; ISSN 0717-6996 https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-69962020000200012

- DÍAZ, Francisco; BERTOLOTTO, Hugo. “Fernando Castillo Velasco: El ojo crítico y autocrítico del hombre que marcó su huella en la arquitectura chilena”. Ciper Chile, 02 de agosto de 2013. Disponible en: https://ciperchile.cl/2013/08/02/fernando-castillo-velasco-el-ojo-critico-y-autocritico-del-hombre-que-marco-su-huella-en-la-arquitectura-chilena/

- VALDÉS, Adriana. “Experiencias de un arquitecto: entrevista a don Fernando Castillo Velasco”. AISTHESIS: Revista Chilena de Investigaciones Estéticas, no. 6 (1971): 123-128. Disponible en: http://www.revistadisena.uc.cl/index.php/RAIT/article/view/9014

- LAVANDEROS, Fernando; Fernando Castillo Velasco explica la Unidad Vecinal Portales y Quinta Michita; Video Clip

https://www.archdaily.cl/cl/02-279578/video-fernando-castillo-velasco-explica-la-unidad-vecinal-portales-y-quinta-michita - CASIOPIA: UNIDAD VECINAL PORTALES, Escuela de Arquitectura y Diseño, PUCV Wiki Entry https://wiki.ead.pucv.cl/index.php/Unidad_Vecinal_Portales/_Estacion_central

- GANNON, Francisco Chateau, "El espesor del suelo urban. Unidad Vecinal Portales"; Tesis, Nov. 2022; PUC.

- GALLO, Juan José Pool. "Rescate de áreas patrimoniales en obsolescencia, la unidad vecinal portales", Tesis 2008, Universidad Católica de Chile. https://issuu.com/sebastiannunez09/docs/rescate_de_areas_patrimoniales_en_o

- SAHADY, Antonio; GALLARDO, Felipe. "Algunos antecedentes para el estudio de la doctrina habitacional de la corporación de la vivienda" ; Revista Universidad de Chile, boletín 37, articulo 74, 1999. https://revistainvi.uchile.cl/index.php/INVI/article/view/62100/66344

- CUBILLOS, Jimena Silva. “El Legado de Castillo Velasco” ; Revista VDhttps://arquitectura.uc.cl/news/3183-el-legado-de-castillo-velasco-revista-vd.html

- Guendelman, Rodrigo. “10 Años sin Fernando Castillo Velasco”; La Tercera;

https://www.latercera.com/la-tercera-sabado/noticia/columna-de-rodrigo-guendelman-10-anos-sin-fernando-castillo-velasco/O6LQWXIUU5BOLIRGFF7MFGGGEY/ - Chelech, Faride Zerán. Tiempos que muerden: biografía inconclusa de Fernando Castillo Velasco. Ediciones UC 2018 , https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv14rmrkp

References Photography/Arch. Plans from

Casiopea, PUC, Tesis de Doctorado Humberto Bonomo, Fondo René Combeau Sergio Larraín García MorenoPUC, Carolina Katz + Paula Nuñez, Castillo Velasco , Humberto Eliash, Hidden Architecture

Photos from Flickr Users: edoguerr, Fernando Leiva, Tae Sandoval,

Others photos by Leafbox, Santiago, Chile, 2023

Translations from Spanish into English by Leafbox.