Notes: Dachas or Lessons on 'Keeping the Country, Country'

The wait list to secure a personal plot in my community garden is currently over 3 years. Such is the demand for a little 60 square foot piece of raw earth.

Here in Hawaii, the year round climate allows one to cultivate an array of produce: sweet corn, basil, cucumbers, sweet potatoes, kabocha pumpkins, edamame soybeans, purple spinach, dragon fruit pitaya, mizuna. Other members nurture difficult wily tomatoes, volumes of dinosaur kale, bok choy, daikon radishes, countless lettuces. Ringworm snails, coconut beetles, monarch caterpillars, and mice present challenges; meanwhile, wandering thieves occasionally snatch from our bounty, adding to our frustrations

The community garden is more than a collection of plots; it’s a small microcosm of the local society.. Here, retirees and multi millionaires alike, house cleaners and hedge fund traders plant side by side creating a rare class less enclave. Conversations never seem to drift outside of the garden, to divisive politics or class indicators; instead, children play, kapuna (elders) till the soil, grumpy others work the worm and compost beds to build smiles as the amazement of children running and playing through aisles.

A mosaic of languages and local heritages. A Vietnamese auntie who works at the nail salon down the street grows copious bitter melon: ‘Good for diabetes,’ she touts the health benefits. An elegant lady kneels softly talking to the most beautiful rows of kalo (taro) plants. While I struggle with mint and cilantro that don’t grow for me, others find success in their various herbs, fruits and medicinal plants.

Selections of fruit trees line the garden acreage: strawberry guava, banana (a chance to get a banana flower), coconut, purple and red sugar cane, prickly soursop, and endless flowers to make leis and garlands. Birds weave nests in the branches of these trees, birders watch and listen to the songs. Feral chickens, scuttle energetically in dance across plots, their presence an amusement but also a frustration as they peck at plants and disturb the tended beds. In a cozy corner of the garden, a round, portly pig affectionately named "Chunky" eagerly awaits, delighting in the tossed scraps and carrots that come his way.

A large community compost system is worked and is even enriched by zoo animal droppings. Giant tons of garden and food scraps are turned into black gold. Mimicking the eager joy of “Chunky” the pig, gardeners arrive in happy honks armed with buckets, ready to partake in the distribution of the fertile compost essential for their hungry plots.

For the modest and accessible fee of $18 dollars a year, covering the essential water service and trash collection volunteers coordinate management and coordination of different tasks and teams: the seeding team, compost crew, plot assignment and enforcement, the overseeing elected board. Each plot equipped with a “mailbox”, anonymous rule enforces discreetly place warnings - gentle reminders that still anger some, plants shouldn’t tower beyond 5ft , or cultivating “illegal” plants like marijuana is prohibited. A spectrum of personalities ebb and flow thru the seasons. Disagreements surface, some clash, as seeds wildly propagate across plots with the trade winds, promptings remarks like, “Hey, trim back your tomato bush, its jumped into my plot again!”

“Be patient, like a farmer.” another will echo the wisdom of the Thai monk Ajahn Thate in response.

This philosophy underpins our collective ethos: nurturing patience in planting and watering, allowing nature to unfurl their magic at their own pace, rather than hastening the growth crops.

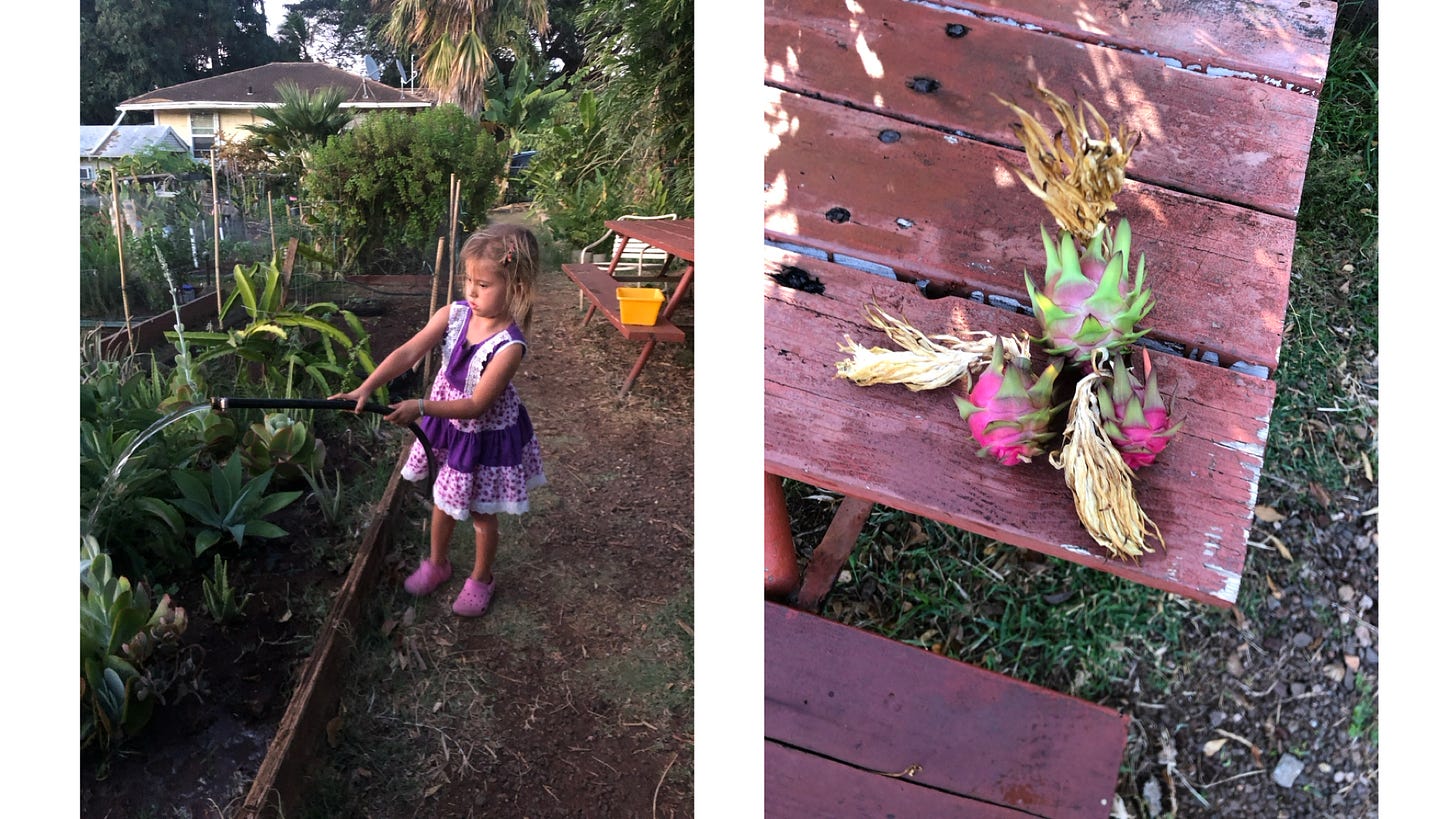

Some manage micromanage their plots, weeding every “non desirable’ form of life, others go for the “do nothing” approach of Masanobu Fukuoka's natural farming where nature takes control and minimize human intervention. We’re a mix of both. I cautiously avoid meddling with my thriving dragon fruit that yields enough fruit for a steady stream of homemade pitaya ice cream.

A communal table serves as a hub for sharing, trading or discarding of bounty. My daughter ecstatic to find her much-loved sugar cane, or the ginger, and local orange turmeric.

This garden is a microcosm of decentralized, small-scale farming. It reflects a mindset of abundance and fosters community, leisure, education, exercise, and local food production.

Globally, small-scale farming has proven essential in times of crisis. In Post-USSR Russia dachas, their small garden plots serve essential in food supply, community anchoring, exercise and improving life. When the USSR state’s sponsored and heavily subsided industrial agriculture systems collapsed and people were able to avoid famine thru the small scale farming.

According to the Small Farmers Journal “dachas cover about 3% of Russia's arable land but produce approximately 50% of the country's food by value.”

“According to official government statistics in 2000, over 35 million families (approximately 105 million people or 71% of the population) were engaged in dacha gardening. These gardens provide 92% of Russia’s potatoes, 77% of its vegetables, 87% of the berries and fruit, 59% of its meat and 49% of the milk produced nationally. There are several studies that indicate that these figures may be underestimated, as they don’t take into account the self-provisioning efforts of wild harvesting or foraging of wild-growing plants, berries, nuts and mushrooms, as well as fishing and hunting that contributes to the local food economy.”

These tiny little gardens present against the false dichotomy often presented in discussions about agriculture: commercial versus small-scale farming. The diverse range of farming sizes and methods is essential for a resilient food system and highlights the wastefulness of the current food distribution system.

When viewed solely from an economic perspective, dachas or the community plots of Hawaii might appear illogical. The labor invested, in terms of its dollar value, exceeds the financial return from the harvest. However, the true purpose of community garden extends far beyond mere economic metrics. These gardens provide active leisure and reestablish a connection with the land, aspects that traditional economic assessments can overlook. The time spent in these gardens is multifaceted, encompassing relaxation, education, entertainment, and exercise, with food production being a significant added benefit.

Besides contributing to food security through a robust, decentralized, and local food system. Environmentally, it supports agricultural sustainability, biodiversity conservation, and the preservation of heirloom plant varieties. Socially, they foster community building and a deeper bond with nature and the land.

Gardening transcends being merely a pastime; as Charles Hugh Smith aptly puts it, it's an exercise in "self-reliance," fostering real, long-term value. Smith's perspective on gardening emphasizes the intrinsic value of community over material wealth:

"The best protection isn't a 30-room bunker; it's having 30 people who care about you."

This statement encapsulates the essence of gardening's value—it's about forging connections. A small 60 square foot plot linked to 30 others holds more worth than the secluded bunkers of billionaires on Lanai and Kauai, which, in any crisis, are likely to be targeted and looted first. The modest gardener with a community plot embodies a deeper sense of security and belonging.

Expanding on this thought in his essay “Self-Reliance, Taoism and the Warring States” Smith asserts:

“Since those 30 have other people who care about them, you actually have 300 people who are looking out for each other, including you. The second best protection isn't a big stash of stuff others want to steal; it's sharing what you have and owning little of value. That's being flexible, and common, the very opposite of creating a big fat highly visible, high-value target and trying to defend it yourself in a remote setting.”

In times of crisis, a small, tightly-knit community garden offers security and resilience far surpassing that of an isolated bunker. This principle holds true not only in times of adversity but also in periods of economic growth or political stability. The value of these diminutive garden plots extends well beyond their physical dimensions, providing joy, fostering connections, each action a contribution to a unity and possible hopeful blueprint for something larger and local. These local efforts also highlight the contemporary over-dependence on complex technological systems while advocating and modeling a simpler, more self-sufficient ways of living.

Matches the sentiments seen on local bumpers or heard on the North Shore in the mantra: “Keep the country, country”.

Prayer call reminders from the medina that is nature, to maintain and ground your feet in these little pockets of tranquility and activity.

"The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings." Masanobu Fukuoka, The One-Straw Revolution

Sources:

Fukuoka, Masanobu. The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming NYRB Classics 2009

Smith. Charles Hugh Smith - Self-Reliance, Taoism and the Warring States Of Two Minds 2024

Scott, Stephen. Russian Dacha Gardens Small Farmers Journal 2015 https://smallfarmersjournal.com/russian-dacha-gardens/