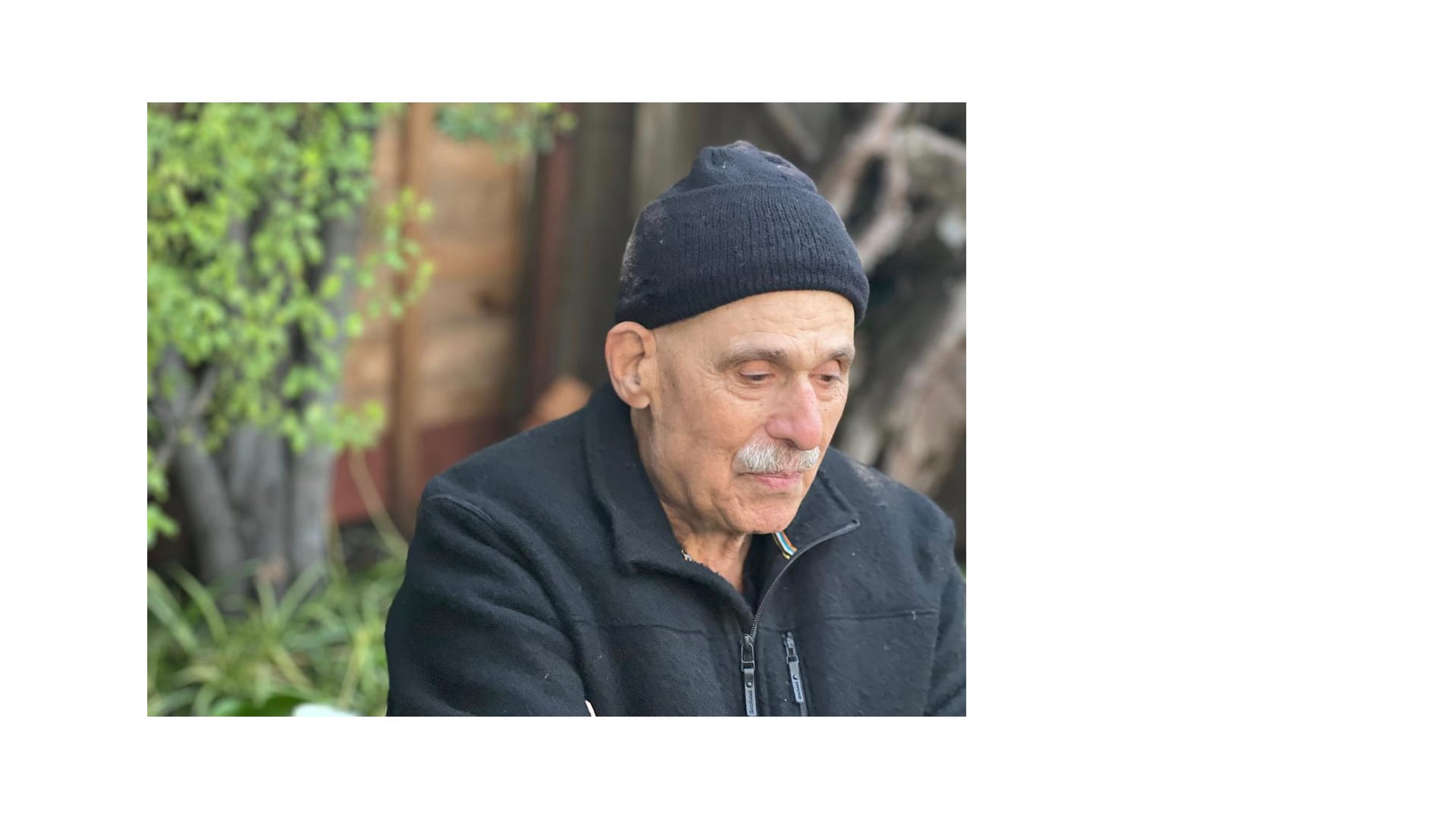

Interview: Thomas Farber

Today I had the pleasure of connecting with fellow surfer and ocean lover Thomas Farber. Thomas Farber is a master in capturing the essence of life’s intimate moments, condensing the most profound into beautiful profound vignettes.

Awarded Guggenheim and, three times, National Endowment fellowships for fiction and creative nonfiction, Thomas Farber has been a Fulbright Scholar, recipient of the Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize, and Rockefeller Foundation scholar at Bellagio.

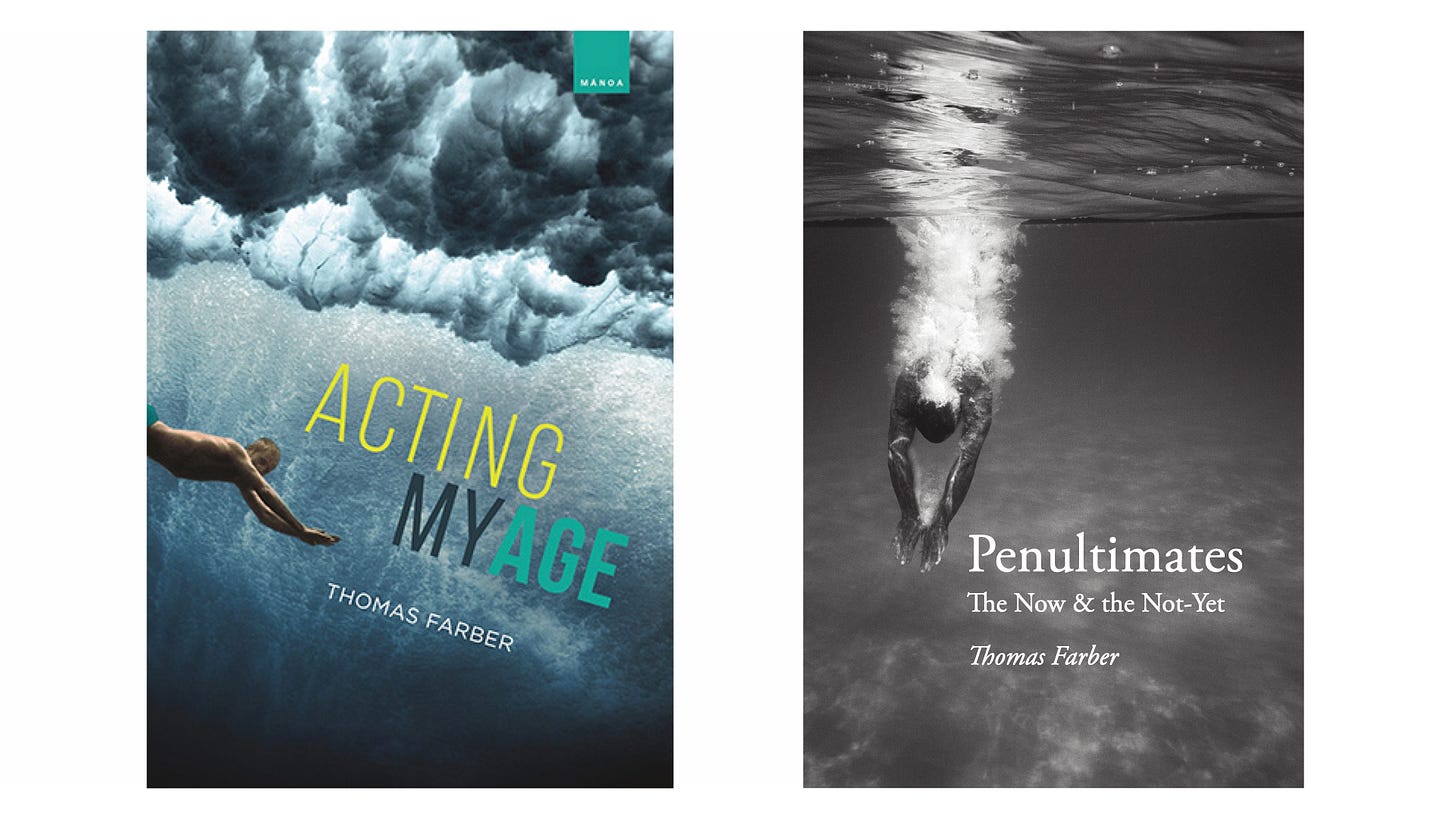

An Author of over 20 books of fiction and creative non fiction and has just published two new collections, Acting my Age and Penultimates.

Thomas Farber's other recent books include Here and Gone, The End of My Wits, Brief Nudity and The Beholder. Former Visiting Distinguished Writer at the University of Hawai'i, he teaches at the University of California, Berkeley.

We connect today about his latest meditations on life, death, writing, the sea, women, Diamond Head and much more. All with humor, humility, gravitas, and wisdom, I’m grateful for his enduring lessons.

Time Stamps

(2:27) Wearing Black, Theatre Playing the “writer”

(4:06) Publishing Acting by Age with Manoa Journal

(9:33) Growing Older/ Acceptance / Being a Child of the 60s

(11:06) On Spirituality

(15:57 ) The Banayan Tree / Hāmākuapoko Ruins Maui

(17:57) First Trips to Hawaii 1971

(21:56) Collaboration with Wayne Levin

(27:40) On Sailboats / The Book Of Love

(30:18) On Minimalism, Scuba Gear, Surfboards

(32:04) Epigrams

(37:55) The 96 Year Old ‘Carrot’

(39:32) On his novel The Beholder, writing about physical love

(42:27) Doom Scrolling

(44:44) Advice to young writers

(46:32) Making Amends; New Projects

(52:00) Jean Cocteau and the importance of readers

More Info @ https://thomasfarber.org/

Excerpt: Ruins 1999 By Thomas Farber

Headshot Credit: Ugo Corte

Book Cover Photos: Wayne Levin

Hāmākuapoko Mill, 1979.

Photograph by Geoffrey Fricker

Transcription (AI Generated Transcript - please excuse any mistakes in transcription!)

Leafbox :

So I was at the library here in Hawaii, and I just was looking through the shelves and I saw your acting, my age book, and I read that a few months ago and I loved it. And then you told me about your new book and I connected. And so thank you for inspiring me. But my first question I was going to ask, just looking through photos of your past and your, I wanted to know about your uniform. There's a period when you shift your clothing to black. So I wanted to understand what effect consciousness that Was

Thomas Farber (02:27):

Theater. Yeah. I was playing the writer and in Europe, writers wear black, New York City at that time in the sixties and seventies. Writers mostly were black, and it seemed to suit me, so I went with it and pretty much stayed with it. Later I got into Cuban music and dance, but even then I think I wore black, and I've been faithful to my costume. You can't go naked in this of tears, as you know or most places. And so I stayed with it. I'm just actually getting some T-shirts made up that say, Pen Ultimates on the front, the cover of the title of the new book. And on the back is the Wayne Leather photo that's on the cover. Yeah,

Leafbox (03:22):

I mean, maybe going to that cognitive choice, are you still playing the role of the writer or what role are you playing now with your latest book?

Thomas Farber (03:29):

Yeah, I think black is simply comfortable to me though. I have some Tahitian T-shirts. My wife, among other things is in some halao Tahitian dance halls. And so I'll go with the colors that they have in order to be able to suggest that I know something about Tahitian dance. It's my wife though.

Leafbox (03:54):

I was curious about this change in tone between Acting My Age and Penultimates. I don't know if maybe you can explore that or where your mental state was or

Thomas Farber (04:06):

Well, so it was my great good fortune that press, which really means Manoa Journal, which was under the great editor-in-chief Frank Stewart for 30 something years. So I had just had another major surgery at the end of 2019 as I was finishing Acting My Age and I survived it. And the pandemic also then began, I got out of the hospital just in time. So I sent the manuscript to Frank Stewart and Pat simply to read it and see what they thought. And Frank wanted to do it as an issue of Manoa Journal, which would be a book, the book that you saw. And they did an amazing job, those photographs of my longtime friend and collaborator, Wayne Levin, and my friend Jeff Riker's, photographs of the Ruined Sugar Mill at Hāmākuapoko on Maui. So that was just a great blessing. So if I finished the book in early 2020 and it came out at the start of 2021, by then I was a writer again, nothing else to be doing.

(05:24):

So I started what became Penultimates, but now Covid was on my mind and everyone's mind. And also there are things toward the end of Acting My Age, like a quote from Wallace Stevens, the famous American poet who said, each person completely touches us with what he is and as he is in the stale grandeur of annihilation. Well, when I read that in my reading toward Acting My Age, I thought, this is over the top. The words were too big, stale grandeur and so on. And also we don't know that each of us doesn't know everyone else and so on. But then I thought about it more, and I realized that a lot of my friends were ill. A lot of my friends were in trouble with aging. And so now the Wallace Stevens began to ring more true. Each person completely touches us with what he is and as he is in the stale grandeur of annihilation.

(06:33):

So that was part of my mood as I went on from Acting My Age because I'm a writer. What do writers do? They go on, Samuel Beckett said, I can't go on, I'll go on. Right? He wrote, so the mood was darker. I think in PenUltimates, Penultimates means the next to last, right? And the subtitle is the Now and the Not Yet. So I was having fun with all of this, with being my age, with Acting My Age, but the terrain was getting darker. You can see the difference in the two things I do to Donald Trump. In Acting My Age, I merely, I don't wish him ill. I simply have him alone on a beach in Hawaii wearing a full wetsuit and a wetsuit cap and goggles alone, he's utterly alone on the beach. This man who's never alone, no phone, no retainers, and he's on the beach staring out at what Dan Duane calls the inhuman mass. And what happens to Donald Trump in Acting My Age, he shits himself if he remembered that because he's terrified being alone. And of course, like all humans, he's going to die. I am not wishing him ill, but it's his fate as it's the fate of everyone, but in an ultimate side, do something quite different to Donald Trump in a similar chapter. And I don't know if I should say what it is.

Leafbox (08:09):

Well, I know what it is, but maybe we'll leave it for future readers to find out Cliffhanger. I was going to argue that, I mean, I'm just thinking of the poem with which I was rereading this morning about the Monarch butterflies and how with the interaction with the Manuel character and how he says forgiveness first. And you say acceptance, and there's a, I wonder if you've, most of your books I've read before weren't at all political. I felt like they were just, you're more interested in the female form, love male female relationships, Penultimate. There's kind of an anger towards Trump, towards politics, towards social media. But the Monarch poem, you have this forgiveness acceptance. So maybe you can talk about that or how you find all this fitting into,

Thomas Farber (08:55):

I'm a child of the Sixties, right? So the Vietnam War, I won't ever forgive those Harvard people. I was a student at Harvard and they all, in the sixties, they migrated to Washington and advanced to Vietnam War and Kissinger and so on. So I'm a skeptic about power, political power, and government. And that's been a constant in my life. Even though I teach at UC, Berkeley, I'm probably a moderate in this town. There are people, well, to my left, I have political concerns for sure.

Leafbox (09:33):

So I just wondered, as you grow older, do you have more of a forgiveness toward that past or an acceptance, or what's your relationship to that power?

Thomas Farber (09:44):

I think there's a part of me that feels that people are helpless, they can't control themselves. And then there's another part of me that feels being my parents' child, that we have to make ourselves be the best that we can be. And so I think I probably move like many people between both poles. I think it's very hard to, let's say this past spring, I taught a graduate nonfiction writing seminar. It was a wonderful seminar, 10 students and grownups age, early twenties to early forties from all different fields, very talented people. One of the things about writing memoir is that people imagine they're telling the true story. Well, it might be true at the time to them, but of course, our memories are very fallible. Our sense of outrage is usually more easily directed at others than at ourselves. I would say as one gets older, if one is not embittered, one becomes in a way more tolerant of the situation that others find themselves in because they're human, and how could they help it? I suppose that means that at some point, I should have a great sympathy for Donald Trump, but I'm not there yet.

Leafbox (11:06):

Do you have a spiritual practice at all? I'm curious about your spiritual background. You talk a lot about your mother and your father, but the spiritual basis is not that clear to me.

Thomas Farber (11:16):

Well, my father was a Christ figure. He was an extraordinarily famous physician. He built the first hospital in the world for children with cancer. And he never took a private patient. He was the child of immigrants. He was a poor boy, blah, blah, blah, an amazing human being. He never talked about any spiritual practice. My parents were Jews, and they were publicly queer. They were Jews, but they were very secular Jews. So the example I had was of someone doing extraordinary things, celebrated for his compassion and kindness, but he had no, what shall I say? He had no rap about it. He wasn't giving a formula. He was simply, you might say, living by example. So I would say that in terms of larger spiritual practices, also, when my father would get yet another award, and he didn't care about awards, he just was doing what he felt he needed to do, he would always, in those years in the fifties and sixties in Boston, he would be introduced by a rabbi priest and a minister who would talk eternaly introducing him.

(12:34):

And they weren't manifesting goodness as he had. And so I think I grew up very secular, though my mother loved and retold stories from the old and New Testament. She loved the stories, but they didn't want to be in any organized religion. And I suppose that when I came to California in the mid sixties as Buddhism was taking hold everywhere, I suppose I had a chance to join into that in some organized way, but it wasn't for me. I think I would say that in a way that writing, it's not my religion exactly, but it's my spiritual pursuit to try to do it as well as I can. That's an odd way to put it, but I think it's close to true. I don't need anyone to follow me in my writing and I don't organize it. But I would say I'm trying to say true things to people who are in need of hearing it if they want.

Leafbox (13:45):

Do you have any relationship? What is your relationship in terms of fear towards death? I mean, after your heart surgery, and I mean, being in Berkeley, it is just funny because I interviewed someone who was also a secular Jew, and he was telling me about the, as he grew older, he really had a kind of awareness of consciousness, even as a physicist. So I'm curious where you think you're going to be going in the next 20, 30 years or what you think hopefully will happen next.

Thomas Farber (14:12):

My father was a pathologist by training. And what did he do? He did all of the autopsies of children at Children's Hospital next to Harvard Medical School where he was a professor. So he saw death all the time. I never once heard my father or mother talk about anything beyond this life. They didn't have a rhetoric about it even. It just didn't come up as a subject. And I think I inherited that unthinkingly, and without arguing it one way or the other, I mean, I don't have any convictions here, but I would say that prior to live in this life, well is a full-time job. My mother said, some kids came to see my mother who wrote many books. They asked her if she was afraid of dying. And she said, well, she hoped to make as graceful an exit as possible. But that's often not given to us, often in old age, in our culture particularly, people suffer and suffer a long time, and the people caring for them suffer a long time. I would say my interest is more on that end of things, the end of life rather than on death. And what happens after death, though? I know that subject intrigues a lot of people, and I'm not against them being intrigued by it.

Leafbox (15:41):

Well, the reason I bring it up is that you had that in Acting My Age. You visit the ruins, which I thought was one of your best pieces in that collection. And I think the last line was about the Banyan tree looking back on your mortality. So I just wonder how that fits into everything.

Thomas Farber (15:57):

Well, I just reread that piece. One of the things about getting older is that you can't hold all of your books in your mind all the time. There are too many words, too many books, 20 something books. But I reread the Ruins piece. So Jeffrey Fricker a great photographer. I had met him here in California, and we had a shared interest, of course in Hawaii. He sent me to Maui in 1999 to go to the Kuah Pko Mill, the Ruins. I was amazed by how powerful, how powerfully I was affected by that trip. In the end, the Banyan tree as the Banyan tree or trees, it's a little hard to say with Banyans what's going on. They overgrow the mill, the ruin, the mill. It doesn't take a rock and scientists to start thinking of mortality, because that was once a powerful mill had hundreds of workers and foreman and machinery.

(17:01):

But look at it now. It's an empty building with Banyan trees overing it. As I reached the conclusion of that piece, I kind of imagined that like Jeffrey Fricker in a way, who was so obsessed with the mill for years, he kept going back to photograph it again and again, I'd be, I began to think that oddly Geoffrey Fricker having sent me to the Hāmākuapoko Mill, put me in touch with the Banyan tree, and that our fate was shared. It wasn't a flimsy notion. It was deeply felt. Yes, but that's as religious as I get.

Leafbox (17:42):

Well, yeah, I would say the 'aina there is touching base with you, which maybe connects me to my next question is maybe you can just iterate your history with Hawaii. I know originally from your Boston then to Berkeley. What brings you to Hawaii and Polynesia

Thomas Farber (17:57):

So what happens is friends invite me over to Hawaii in 71. I see it for the first time. I'm a water person, but I've never seen warm tropical ocean. I saw a great body surfer, one guy just out there, and that was like a revelation, but I couldn't be in the ocean all day long in Hawaii. And I'd be in the library trying to figure out where I was and what the history was here. And of course, I was a Bostonian. When you're in Hawaii, you start seeing the architecture in the churches of the Boston I grew up in. That was that influence, that Protestant missionary influence was of course, something when I was young, you didn't like, because on Sundays, the whole city closed down tight, the blue laws, the religious laws. So I was a little startled to be in the tropics and seeing missionary Boston.

(18:57):

And then of course, being a Bostonian myself, carrying some of that karma, you might say. So then other friends had a place on the north shore of Maui, just a shack really. And I was able to go there frequently and just spend time. And then I got into surfing. As you know, that becomes an obsession of its own. And so for some years, I would spend months at a time in Hawaii between books, particularly after I'd finished a book. I never wanted to go right on to another one. I wanted to wait and see if there was going to be another one. I didn't see writing as a career. I saw it as a book. I didn't see writing as a career. I had to be called as a book. This is a little bit about this notion had to be called, this is a little bit about this notion of writing, spiritual pursuit, secular.

(19:49):

I only wrote books when I was called Spiritual Pursuit. I didn't write them for money. For money. I didn't write business. The business of books, none of that. None of that. I'm surfing all the talking in Hawaii. And then there are some readers, a writer in Berkeley tells me that taught me visiting writer ity. I taught visiting Santa Cruz, UC Berkeley, to create every five years. I would teach for a semester or two. That was it. I didn't want to climb that ladder of academia. I met at the University of Hawaii, and they brought me in as visiting distinguished writer. Well, that changed things in Hawaii for me, because before then, my community was really the beach and people on the beach, most of them never asked me what I do. People weren't interested. I wasn't particularly interested in the jobs they had. I was interested in surfing in the ocean, and that's what we talked about.

(20:47):

But now I was at, and then I was at the East West Center as a visiting fellow. So now I was in the fabric of the community in a different way, though I was still surfing. And while teaching at, I was mentoring and meeting the first wave of post-colonial Pacific Island writers, people from Tonga, Rotuma, Samoa, Fiji, inevitably. Then I went down to their world to learn more about what that was like. And I still have great friends from that part of the world. Her Herko Tuman, a little Polynesian place north of Fiji. He's a professor at the now, the great Tongan writer, a marvelous sadist. So my life was changed by that connection to the University of Hawaii and the East West Center, and it put me in a different place. Being in Hawaii, I was still a howley. I was still a mainland howley, but I was getting in deeper, you might say,

Leafbox (21:56):

Talking about going deeper. Maybe you can parallel that to your scuba diving. And how old were you when you started surfing, and did you ever surf when you returned to San Francisco or Berkeley or

Thomas Farber (22:06):

No, no, I hate cold water. When I was a kid, I was skinny, and the water in the lakes in New Hampshire was cold, really cold. I've surfed almost never in, I've surfed a little bit in Santa Cruz because when I talked there, but I really don't like cold water, and I don't like the getting into a full wet suit and all of that stuff. I'm talking to the people in the English department at, and I see the first issue of Manoa Journal, this beautiful literary journal that Frank Stewart edited for 35 years. And he's an amazing man of letters. You may want to interview him sometime. So I see they have pictures of by Wayne Levin. So I find out, this is pre-internet, 1990. So I find out where he lives. He's visiting his parents down in Hawaii, Kai. He lives on the Big Island.

(23:04):

And I go to see him and he and his wife being starving artists at that time, they're hoping I maybe am going to buy a print. But no, what I'm saying to him is, I want to work with you. Because I had finished another book, a book about being a writer called Compared to what? I didn't know what was next, if anything, because I thought I might be saying farewell to the life of being a writer. I was weighing its qualities either to continue or to let it go. There's a lot of beautiful things you can do in the world. You don't have to just be a writer. So one day I'm surfing off of Diamond Head at First Flight. There's nobody there. It's incredible. The city of a million people. And I'm all alone. I'm rising and falling on the swell. And it occurs to me that maybe I'm the fixed object and diamond head is rising and falling.

(24:01):

And I say, whoa, that's an interesting notion. I said, maybe I could write about that. And that starts the first of my water books, which is called On Water. So when I go to see Wayne, the reason I'm going to see him is because I've had that idea. I'm going to write about water. I've seen Wayne's photographs mostly at that time. It's all color photography of surfing, marvelous photography. Wayne is doing black and white in the water photography, maybe the only person around doing such a thing. So I see Wayne and I say, you're a great artist. We ought to team up. And we do. And out of that come three collaborations. The first book is called, I'll Never Forget It. This is what Turning 80 is like. It's very funny, through a Liquid Mirror. And then the second book is called Other Oceans, and the third book is called AKule.

(24:58):

But then Wayne and I have, as you can see from the jackets, photos from my books. I call on Wayne all the time because he's a great artist and he's someone you should talk to too. He's over on the big island. But that first time that we worked together, I go over to his place at AU Above, and we head out in kayaks, and it's very low budget, but we're spending time with dolphins and whales, no expansive gear, just a lot of time in the water. And that's when I get into scuba. But I don't like scuba because I don't like gear in the water. I like surfing so free of gear. I had been a captain of a 31 foot and owner of a 31 foot ocean going Trian, when you don't have a lot of money and you have an ocean going vessel, it means that you're not just the captain, but you're the slave constantly working on it.

(25:58):

And so when I let the boat go, then I never wanted anything with a lot of gear. But I did get into scuba in order to be with Wayne. And then we became faculty on dive boats and got sent by magazines all over the place. So one thing leads to another in the arts, but also in life. And none of these things were planned. I didn't plan to become a writer. I didn't set out to become a writer. A door opened and I went through it, and then I thought about it, and then I, well, I'll try it again. But some people are very highly motivated to become something, one thing to get rich or to be president of the United States. I wasn't clear like that, but I had some great, good fortune. A door opened. I went through it and then, oh, maybe I could try this again.

Leafbox (26:52):

Parallels surfing perfectly, right? You go out there, you don't know where you're going to get some days big, some days small. So I think mean your writing style is very different than Paul Thoreaux. But have you ever met him or talked to him? Because he's another ocean lover on the North Shore.

Thomas Farber (27:08):

No, no. He's not a surfer.

Leafbox (27:10):

Canoer. Kayaker.

Thomas Farber (27:14):

He's a kayaker. Yeah. No, I've not met him. I love to read writers, but I don't have this enormous desire to meet them unless it's meant to be.

Leafbox (27:31):

Well, that's something else you share with Paul Thoreau, because he shares the same sentiment in his books that he never wants to meet other writers.

Thomas Farber (27:40):

In any case, I read it as much as I can. And so I've read him, but meeting writers is a different thing. And I love New York City when I was young, but I couldn't live there because the book business was there. So you are always meeting writers, and they were talking about money, and they were talking about status. I didn't want to know any writers. I wanted writers maybe to know my books, but that was different. I was into writing and I wasn't interested in the literary life. Though over time, I got into that as well. But it happened more organically, I would say. It wasn't a drive.

Leafbox (28:26):

My next question is, who wrote the Book of Love? Is that the one in Yeah. Is that about your catamaran? Is that catamaran? I didn't know you had a Catamaran

Thomas Farber (28:36):

31 foot ocean going trimaran. No, who wrote the Book of Love is a book of stories about men and women in and of love in the seventies.

Leafbox (28:42):

But there Is one at a boat dock, and I remember I read that. So

Thomas Farber (28:46):

Yeah, that's a guy who has children. So I'm down at the Berkeley Marina once again are pairing something on my damn boat. And I had friends who loved to help me work on the boat, but that was different than being responsible for it. So I'm talking to this guy, and it turns out in this one piece about men and women, the books about men and women in and out of love. It turns out he's now got a second crop of kids. And I ask him why? And he says, oh, he says, these things just happen. You don't know why they happen. And that struck me at that moment. It just was a funny thing. So I made a story of it when I sold the boat. I was so relieved to be feeding the burden compared to a surfboard, I'll tell you, even though it was a trir. And so it surfed the waves. But I had a very romantic vision. I thought sailing with freedom. Well, it's more complicated than that. Right.

Leafbox (29:55):

Well, talking about freedom, maybe you can talk about minimalism, and you have the famous cottage, I think in Berkeley that I think is on the cover of one of your books. I remember when I took your workshop, you had an exercise where you had to describe everything in a room. And I enjoyed that exercise. So maybe I'm just curious about, that's why I asked you about the clothing. There's a choice in aesthetics. Maybe you can,

Thomas Farber (30:18):

Yeah, the minimalism. Yeah. So the cottage in Berkeley, so a guy named Peter Conrad, a writer, had a book title I like where I Fell To Earth, and he's just, it's a book about the cities he's lived in where I felt Earth. So I felt earth in Berkeley. I mean, I'd been in Berkeley in the sixties, and then I was traveling and I came back to Berkeley. And this time, as it turns out, I stayed, when I taught in 1980, I lived in Berkeley, but I didn't know anything about the university, the English department, that all, I went up there, I taught at Santa Cruz, and I published three books. I won some fellowships, amazingly, all of this kind of extraordinary fortune. And the chair said, you live in Berkeley, who do you know in the department? And I said, nobody. And he said, but you live here. I said, yeah, because I wasn't trying to be in a literary scene. I was just writing books. And so he hired me, and that's when I first taught at Kelp as a visitor in 19 80, 81 kind of thing. But then in the mid nineties, I had been away from teaching for years. They invited me and we worked out something that could be ongoing and still allow me to be a writer.

Leafbox (31:39):

Well, I'm just curious about when you have this movement towards your writing becomes more minimalistic, you have an interest in epigrams and shortening, simplifying, toning it down, everything becomes more prose. So I'm curious where that parallels with your life movements, maybe your interest in women or just whatever's happening outside the mood. The second shift of your life seems to be more minimalistic. One of

Thomas Farber (32:04):

The epigrams probably my interest in them. So I'm making notes. Writers often make notes. I'm making notes. And now I see some things that seem to be very clever. A man sitting in a cafe watching two young women walk past faster than he could run after them. Now, to me, that's very funny because, so that's a middle-aged guy sitting in a cafe, and that's one of my early epigrams, well, it wasn't an epigram, it was just a one-liner. But then I sort of got interested in that, and I said, oh, other people must've done this. And I start reading them, and of course, the list of Epigrams and Aris is long. And so now I start seeing that there's a forum that might free me of some of the weight, the narrative weight of fiction, or my kind of creative nonfiction, and just go right at human foible or something. That's what gets me started. And as it turns out, I've done many books of the Epigrammatic and always with an essay about how I got to that and why I couldn't just do Epigrams. But they're a lot of fun. They're kind of wicked, a wicked pleasure. For instance, a guy named George Lichtenberg, 18th century writer.

(33:39):

He must not have liked how someone responded to one of his books, and he said, the book is a kind of mirror when a monkey looks in and an apostle does not look back out. Well, you see any writer, any human being who's tried to give something to someone else, of course, has the sensation of having been undervalued. If I were to write his epigram now, I would say a book is a kind of a Rorschach test. What you see is who you are. Now, that's not true. That's not the only truth any more than what Lichtenberg said was the only truth. But it sheds a little light, particularly if you're feeling vindictive. So the Apo Abrahams were a way for me to comment on foible, other people's foible, but also my own foible, because of course, I'm implicated in everything I write, like all writers are implicated in everything they write.

Leafbox (34:43):

Tom, going back to the cafe scene with you, sitting with the two younger ladies racing by, could you talk about your role about writing as a male and masculinity sex and how that's changed across your career? I think in your latest book, you have that wonderful epigram or snapshot of the guy with the 96-year-old with the younger wife direction. So I'm just curious how a lot of your books have sexualized covers relationship with women, so maybe we can go there and see this bigger topic of love, romance, the body.

Thomas Farber (35:23):

Well, I don't know about other people, but when I was young, it was all blind need and not much awareness of the dreams, really, of the others I was spending time with. That's not so unusual, I guess. But also the 1950s I grew up in were really primitive. A lot of people didn't know a lot that's available for them to know now. But there it was, well, who wrote the Book of Love, which came out in 1977, is my effort to come to terms with the change in the game that the sixties had created. Now, there were all new kinds of paradigms about male and female, very different from the 1950s. And so that is a book of stories trying to kind of say, well, this is what it's like now. But I wrote that book while I was safe in the bosom of a wonderful relationship with an amazing woman. So I could look at the dark side of Love's Moon because I was safe and sound and being cared for.

(36:34):

Life went on, let's say in the late nineties. I'm writing a book that turns out to be called The Beholder, which is a story of an older writer, an older male, middle-aged male, a writer with a younger woman, a PhD, young academic, and their tempestuous love affair. That's the only time I ever tried to describe physical love. But I really went into it before. It didn't interest me to try to describe the relationship of male and female bodies, for instance, but in the beholder, I went for it, and I was very, very lucky to see that book published. It was an obsession, a great obsession. And it's a book about heartbreak, right? It's a book about love and reproach,

Leafbox (37:30):

Tom. And then in your latest book, what's your relationship to love and the body now? Because is there a bit of envy with the 96-year-old, or is there a bit of

Thomas Farber (37:39):

Oh, no,

Leafbox (37:41):

Brothership happy for him, or I'm just curious where that

Thomas Farber (37:43):

Well, no, what I'm writing about is a doctor who has a patient who calls his penis his, is

Leafbox (37:54):

It is the carrot right?

Thomas Farber (37:55):

Yeah, he calls it his carrot. And he's a 96-year-old, and he's in the locker room with his friends. So the story goes, this is a true story, but he's boasting about his sexual prowess. In my short piece, the doctor who's younger, his doctor, the old man's doctor, tells his friends this story, maybe to cheer himself up. He's in middle age that he too will have a sexual life at that age. But to me, the whole thing, the gist of the story, really, is that the doctor has to refrain from reminding the guy that he's going to die. People have an amazing capacity to imagine that they're standing on the edge of a cliff, and their back is to the cliff, and it's the Grand Canyon right below them, and they don't see it. Some people are like that. And so that's kind of where that story is at for me. But I don't envy, or one way or the other, the 96-year-old, I would prefer not to be a 96-year-old fool.

Leafbox (39:06):

No, I thought it was humorous. I was just attracted to, I went to Berkeley 20 years ago. So I'm curious what the environment now is in terms of writing as a male, writing these type of relationships. I don't know what the politics of writing are, teaching, writing, identity politics. How does that affect your work today as a writer?

(39:27):

Like you said, would beholder be published today, the Beholder?

Thomas Farber (39:32):

I hope so. I think it's an amazing book. I'm proud of it still. I have a former student who when the book came out and she read it, she of course had to reconcile that with the image of Professor Farber, but professors are humans too, right? And I've been blessed in teaching that people seem to have tolerated what I had to say in the classroom and how I spoke about anything. I'm very fortunate. All universities seem to have a lot of talk about trigger warnings and safe spaces. I haven't really found that in my writing seminars. I found that the students have a lot to say and they're willing to tolerate what others have to say as well. I mean, if you can only imagine what people see in a day on their phones or their computers, it's hard to believe that something in person would shock them.

Leafbox (40:36):

Well, I was going to parallel then to if you have any thoughts about anonymity as a writer for people who are publishing without their names, and then maybe the change in the publishing industry that you've seen over your career.

Thomas Farber (40:52):

Well, I was raised in a period when books were highly valued, and it was a romantic dream to become a writer. That world seems to be going in a hurry. The book market is very different. There's millions of self-published books. There's millions of blogs and all of these wonderful things where people get to talk in different ways and reach vast audiences. All of that is strange to me. I don't do it. I'm not against it. It's not my vehicle. But also the book industry has changed. It keeps consolidating, and that's not good for books. It's not good for airlines when things consolidate and it's not good for books. So I would say to have the dream of being a writer now, for a young person, it must be different than it was when I was young. Though, as I say, I didn't have that kind of dream, but I was able once a door opened to keep finding another open door. As for the content of what people write or don't write, I've never censored myself. I've always written exactly what I wanted to write. I've never sold a book until it was done. I've never shown it to an agent until it was done, and then it's take it or leave it, because otherwise I'd rather be a hairdresser or teaching salsa or martial arts. You know what I mean? There's a lot of ways to live. You don't have to eat shit just in the arts.

Leafbox (42:27):

You have an article or epigram, you call it doom scrolling, which is a,

Thomas Farber (42:33):

Oh, yeah, I wish I'd come up with a term.

Leafbox (42:36):

Oh, yeah, it's a great term. But I'm just curious if you have any thoughts, if you've played around with artificial intelligence and if you have any thoughts about writing with AI?

Thomas Farber (42:46):

No, I have friends who are like Cassandra, who predicted the fall of Troy. They're saying it's the end of writing, and maybe it is because I'm more forgetful than I used to be. I'm more worried about the end of my memory than I am about ai. There are so many things that could keep one up at night, and I'm not conversant with these technologies. It's just not on my computer screen really.

Leafbox (43:20):

Well, I think in one way it's quite liberating if you're open to it, because it pushes writing towards being a pursuit of thinking. And like you said, the vocation for you for writing is to write not for the career or whatever that comes potentially with it. So the people who are fearful of it seem to be writing maybe for the wrong reasons or for the other reasons. So I don't know.

Thomas Farber (43:43):

Yeah, I think the idea of writing this career is definitely going to be very different. My friends who are journalists, and I mean very good journalists, that world is disappearing. That's going down a drain in a hurry. They're just no more newspapers basically, and no more magazines paying people. So that era after World War II where there was a lot of money for people to go to universities, all the veterans could go to school, and the magazines that advertising, that was a whole different thing. Economically, the friends I have who are younger than I am who are still writers, are watching that world disappear. I never looked to it myself, free income. I didn't look to books for income. If income came from books, I was happy, but I didn't look to books to make me a living. I didn't look to teaching to make me a living. I was willing to just go make a living if that's what it took.

Leafbox (44:39):

So is that the advice you give your students then? Or what advice do you give contemporary

Thomas Farber (44:44):

Advice? Well, Pelonius is advice to Laies in Hamlet. He sounds like an old fart, this above altar. I known hard to be true. I don't give him advice like that. I would say that the only reason to write this, if you really need it, who needs it? Often in my seminars, the very brightest students that is at age, let's say 20 to 25, often the very brightest and most talented or apparently talented students didn't become writers. Some of the other ones, the stupid ones, became the writers. And why is that? Because writers have to get made, you see, and then they have to persevere, and they have to want writing more than they wanted something else. More than having a Porsche, probably more than having a rich huge house, probably more than job stability, probably. So that the smart ones often the most apparently talented turn out not to be the writers. Because being a writer, a good writer, takes some dogged persistence and often foolish. There's no prize at the end. Most writers are still trying to get better, even at the end. Well, that's kind of foolish, right? If you're in the stock market and you're a trader, you get rich and then you're just rich. You don't have to do anything more. Writers are always trying to get better, even at the end,

Leafbox (46:22):

Talking about the end. Tom, what you're working on now, because in the end of this pen, the pens, you're suggesting that there's going to be the ultimate. So how is your writing process going?

Thomas Farber (46:32):

Teasing right now, right now, I'm just trying to clear papers. I have boxes and boxes of papers, and I have my mother's papers. She published 35 posts. I have lots of her papers and my father's medical papers. If I could get all of that cleared up, I tease at the end of pens that my next book then would have to be ultimates. What would that look like? I'm afraid. So a guy in Ani Park, a surf buddy of mine, is in one of the many healing groups under the Banyan tree. And I said, what do you do there? And he says, oh, we learned how to make amends. Well, that's quite a word, amends.

(47:22):

I never went to his group, and I've never set out to make amends. But I suppose HAD one could write a book about amens. I tease maybe. I think I tease at the end of pen. Alima said for me, it could be a very long book. Could be multivolume. It's one project I might try to take on, though. I don't know. There's a difference in me. There's the writer in me, and then there's the human in me. That's how I see it. And the writer in me is drawn to all kinds of interesting things. The human in me sometimes doesn't want to do it. For instance, I haven't been back to Boston in years. The writer in me would like to go back to Boston to see it one more time, to register the differences between where I grew up and what it is now and all of that. The human in me doesn't want to make that trip. So the writer in me thinks a book of Amends would be really a great project, but I dunno about the human we'll see to be continued. Right.

Leafbox (48:33):

Well, it's exciting talking to you because it seems that your mood is much better than I felt with penultimate. So it's exciting that you have this energy that you feel rejuvenated. I think maybe Covid was hard for you and the death of friends,

Thomas Farber (48:47):

And you felt it in your book. Well, COVID was incredibly mean for me, but I never got covid. But the closing of the world was terrible, incredibly costly. I think also the culmination of seeing so many friends ill and suffering in Pen Ultimates, I write about my friend Brad, three years, his dying. And it was such a normal story. That's the problem. It was just the most ordinary story in the world, and I couldn't save him. The greatest book title I ever saw by a writer named Leonard Michaels a Berkeley writer. He's dead. He died young. The title was, I would've Saved them if I could. And he's quoting Lord Byron, the 19th century bad boy poet, and Byron's watching a public execution, and he jots a note to a friend, gives it to a servant to take. I would've saved them if I could.

(49:46):

Well, as you get older, you see there's a lot of things you can't save. I couldn't save my friend, my friend Brad. He said I had done great. I had helped him, but I couldn't save him. I had a sister. My older sister just died. I couldn't save her. So that affects your point of view. Then you have to decide what to make of it all. After my father died at age 69, that was not so unusual back in his era. The stuff that saved me wasn't quite ready for him. Well, my mother, who had by then published many books, she then wrote a manuscript called Year of Reversible Loss, year of Reversible Loss, which I saw into print many years later after she died. But it's about a person tried to make sense of the loss of the beloved and the fact that the seasons go right on, and they're beautiful because my mother loved every bit of the natural world in the New England.

(50:53):

She lived in her whole life. But still, if the seasons keep going on, what do we make of the loss of the beloved? Is it like a cloud? And it's simply matter of changing form. My mother didn't try to answer that, but she kind of was trying to think it through. So I don't feel, I think of writing of Pento as an act of love. That is, I made it as good as I can. I worked hard on it. I learned a lot by writing it and by the reading that is part of it. I tried to pass on my knowledge and my wit and my love of language and the music. Of course, now you remember in Penultimate, what's his name, the French poet? Yeah. Jean says that the reader will have to set him free by essentially being so faithful to the book that he replaces the writer who once wrote the book, who's no longer Alive.

(52:04):

So in that sense, I think I gave all my books because I didn't care about the marketplace. I could have given a shit about the market. I just wrote what I wanted and I gave it my best. And so I'm hoping that there are some readers who will come to Penultimates and say, wow, this taught me something I needed to know, or This made me laugh, or this please me. Or I heard the music that this writer was trying to create. Yeah, so I don't see it as a dark book. I don't think of legacy, and I don't think of, I've never thought of books like children, but people do. They do, but I don't. I just see them as a house I built and I tried to make it as beautiful a house and maybe it'll give shelter to others kind of thing.

Leafbox (52:55):

Well, going back to the Banyan trees at the Ruins, I think you're giving the basis for that next generation to grow from

Thomas Farber (53:05):

That Banyan tree. Really. It did register on me. You are quite right about that. And where that piece about the Banyan tree, which includes the roreman in the pickup truck, the Buddha.

Leafbox (53:16):

Yes. I love, yeah, the Buddha, yeah,

Thomas Farber (53:19):

Wonderful character, but that's the world. The world is full of the crude. And then it's also true of surprisingly profound. And the fact that Geoffrey Fricker sends me to Maui to look at that mill and to write something, I didn't know what I was getting into, but it was a rich experience and I'm a lucky man to have had it.

Leafbox (53:45):

Great. Well, Tom, is there anything else you want people to take away from your book or your writing or for the day?

Thomas Farber (53:51):

No, I want to thank you for, if you go back and you read about Jean Cocteau, he's saying that the readers have to find the book and realize essentially the spirit that was contained in the book that needs to be liberated by the reader. And because you came across Acting My Age, you're that person. You've created this dynamic between the two of us, for which I'm grateful. I very much appreciate it.

Leafbox (54:19):

Thank you, Tom. Tom, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it. Very grateful. Sending you lots of love here from Oahu.

Thomas Farber (54:26):

So thank you very much. Take care.