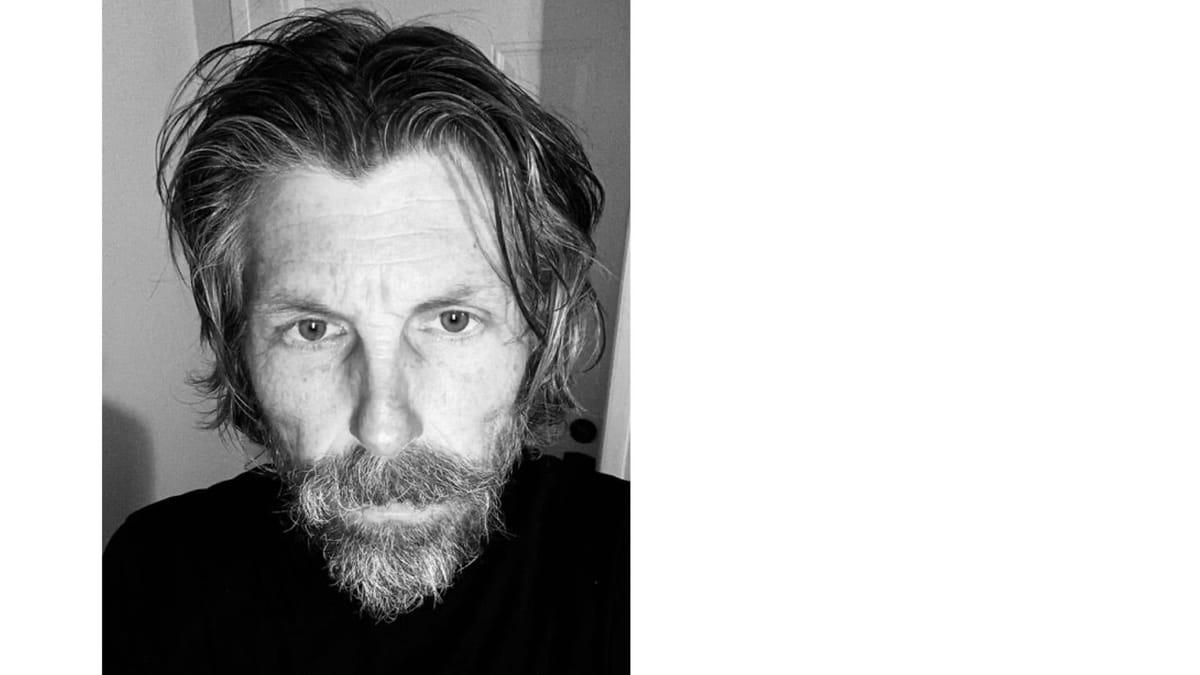

Interview: Stephen Chamberlin

From Coast Guard to Poetic Catharsis: Writing, Psychedelics, and Healing

In this intimate conversation, Stephen Chamberlain, a former U.S. Coast Guard officer, small business owner, and writer, candidly discusses his personal struggles and victories. From navigating anxiety disorders to his cathartic discovery of writing and poetry, Steve opens up about his life journey. He delves into the complexities of moral injury, the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, his 40-year relationship with disordered eating and anxiety, and his pursuit of contentment through nomadic living and creative expression.

Steve's raw honesty provides a unique lens into the challenges of coping with men’s mental health issues while striving for fulfillment. His writing not only serves as a personal outlet but also connects him to a broader community of writers and readers interested healing and self-reflection.

Timeline:

- 01:28 Background and Early Life

- 03:04 Struggles with Disordered Eating, Anxiety, and Joining the Coast Guard

- 04:22 Life in the Coast Guard and Personal Challenges

- 05:47 Post-Retirement Life and Discovering a Nomadic Writing Journey

- 07:35 Exploring New Ventures and Digital Nomadism

- 09:50 Writing as a Cathartic Experience

- 12:41 Peer Support and Mental Health Advocacy

- 17:56 Moral Injury in the Coast Guard

- 38:56 Struggles with Weight and Anxiety

- 40:00 Understanding Male Anorexia and Its Impact

- 40:47 The Battle Between Rational and Irrational Voices

- 42:38 Poetry as a Means of Control

- 45:14 Exploring Psychedelics for Treatment

- 47:28 The Transformative Impact of Psychedelic Experiences

- 58:13 Embracing Mortality and Planning Ahead

- 01:03:28 Future Plans and Other Pursuits

- 01:07:13 Connecting with the Audience

Connect with Steve and his writing @

Steve’s Collections of Poetry: My Raven and My Blackbird

AI Machine Transcription - Enjoy the Glitches!

Steve: Right off the bat, anyone who tries to write understands that writing is very difficult, but what I could do is write about my experiences. The things that I find easiest to write about are things I'm most familiar with, and the thing I'm most familiar with is what I'm feeling and thinking inside. This sounds clichéd, but it's true, cathartic and I found that relatability they feel less alone and that just encouraged me to write more. And quite frankly, if I have one person tell me that, "hey, that thing you wrote really resonated with me or helped me," I'm like a score! if I can help somebody, then it was worth putting out there.

Even if nobody reads them, it felt good to get them out. And it did feel cathartic to get it out. I've come to the conclusion that, what I want to get out of life in my remaining years is as many moments of contentment and fulfillment as I can.

[Music]

Leafbox: Good afternoon, Steve.

Before we start, I wanted to thank you. Even though you're a smaller publisher and you're just starting off on your journey of writing.

One of the things that really stood out to me about your writing is that it feels like it's coming from a very authentic place. And, my own writing and my own efforts across life. That's one of the hardest things to find and be true to so thank you for at least expressing in a way that feels genuine and true and in today's world I think that's a harder thing to do.

Before we start, why don't you just tell us, Steve, a little bit about who you are, maybe what you're writing about why you came to writing.

Steve: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. I'm 57 years old, so I've been around for a little bit and my background is pretty varied.

I grew up in a suburb of Boston. Irish Catholic family, first generation to move into the suburbs from South Boston and second generation of my family to actually go to college. I went to a public school, and it, it was a pretty benign suburban existence.

I would say right up through my university years, I went to a commuter school, UMass University of Massachusetts in Lowell, Mass, and something I could afford in that day and age by working part time and lived at home and really had no, what I would call significant life experience. Until I left home and went to the Coast Guard's Officer Candidate School after college.

But I think it is noteworthy to say that like a lot of typical families of that era, I had, it was dysfunctional, but most people have some sort of dysfunction in their family. Alcoholic dad, very much a perfectionist. Everyone in the family seemed to be driven by anxiety created by their predecessors and I picked that up as well.

And it's notable to say that I developed an eating disorder in my high school years, which is a male in the 1980s I think was very eating disorders are stigmatized. Among all genders, even today, but being a guy in the 80s when there was really no infrastructure set up to, to diagnose, recognize, or treat it made it particularly challenging.

And I really got into triathlons and long distance running and marathons. Got to a really unhealthy weight. And, my mom did her best to get me in with psychologists and psychiatrists, but none of them really had a handle on how to deal with somebody like me. And it, it caused quite a bit of isolation for me in high school.

College was a little bit better simply because it was a commuter school and I would go do my work and come home. So I became quite a loner, but, for reasons that I can't describe other than just being impulsive in my early years, I applied after college to the Coast Guard's Officer Candidate School and somehow got in and spent about four months down in Virginia in basic training and then the next 25 years in the Coast Guard and the eating disorder I somehow managed.

Gained some weight was always a little odd with my eating habits, but and very excessive with my exercise habits and very rigid as I am to this day. But those 25 years in the Coast Guard were both fulfilling and beset by a little bit of inertia. I think it's a challenging job, but and as you get more.

Responsibility more senior becomes more challenging and more all encompassing, but by the same token, it's a secure job where even though you move every couple of years, the culture remains the same. So for a guy with anxiety and quite frankly, anorexia nervosa is an anxiety disorder when you get right down to it.

The Coast Guard was a relatively comfortable place for me. In 2015 I was serving in Alameda and living in San Francisco, which is where you and I met. And I also retired from the Coast Guard that year. At the time I was married, but my anxiety, which demonstrated itself in those days, I think is more of a extreme dedication to work kind of a workaholism, if you would call it that really, destroyed my marriage.

And by 2017, 2018, we were divorced, which was really, for me, the point in time in which I think I gained a level of self awareness that A lot of my peers do not seem to have, and I'm not trying to be, I'm not trying to brag or anything like that because I tend to surround myself with friends like you who are self aware and do look inward and do understand they have egos and those egos are rather hard to control.

And but having that self awareness. This is really a great way to determine when your ego is getting the better of you. And it was the divorce that kind of opened my eyes to the fact that I had not been a good husband. That my dedication to work was one of these fleeting needs for professional affirmation that came at the expense of any sort of long term personal contentment.

And it was that self awareness obtained relatively late in life, my late forties, early fifties, that led me to writing and led me to trying several other Endeavors. I worked a little bit in the wine industry for three years and learned what I could at a small five person wine startup.

I impulsively bought Airstream trailer and spent about a year and a half, 2020 at the Covid years. As a matter of fact I launched my digital nomadism, as I called it in March of 2020. No, great plan to do that, but at the same time, the whole country. Pretty much shut down and spent a little over a year place really enjoying that kind of existence.

And fortunately with a military pension and a small business running some companies, alcohol compliance operations, I was able to support myself. And not like minutes overhead on the Airstream trailer I had I decided to stop and go back to Massachusetts for a couple of years, rented a small house.

And my mom and dad are there. They're older now. They're still in the same town I grew up in. My sisters are there. But I found after about three years there, my eating disorder had I guess I'd say I relapsed a little bit, not full scale after decades of it being more or less managed, but not certainly cured.

Realized that I was going to be stuck with that for the rest of my life, but also thinking my time in Massachusetts was a good time to really become introspective, maybe more present, practice meditation investigate psychedelics which you helped me with Three years later, to be honest I didn't do it while I was there, just thought about it a lot and and really work on myself.

And quite frankly, after those three years had passed I felt that I honestly, I've been inside my own head so much time that I was feeling worse, not better. And I was also feeling restless, which I did not expect to feel after decades of moving every couple of years. I thought I'd be quite ready to settle and I wasn't.

So I very impulsively decided that rather than using a trailer, I'd try and see if I could do the same Nomadic existence with Airbnbs, if I could find Airbnb hosts who would rent long term to me. And right off the bat, I found somebody who gave me a two year lease on a place in Florida.

But the writing really started I'd say around the time I launched in the Airstream 2020, where I started a blog about, my trip. And right off the bat, anyone who tries to write understands that writing is very difficult. In all people who write fiction I cannot write dialogue.

I it's way too challenging for me. But what I could do is write about my experiences. And I think what you were getting at the beginning of this conversation was that, the things that I find easiest to write about are things I'm most familiar with and the thing I'm most familiar with is what I'm feeling and thinking inside again, something I never could have done before my divorce.

But it helped me get to a place where I felt it was almost, and this sounds clichéd but it's true, cathartic to write about things that I was feeling, I was thinking and then publishing them in different venues like Substack and where I am now and Medium where I was before and getting not a lot of feedback, some feedback.

And I found that relatability was on one hand, a really good hook for a personal essay because people enjoy reading things that are relatable to them. They feel less alone. I enjoy getting that feedback for obvious reasons. Somebody liked what I wrote, but also because I feel less alone while somebody else feels this way too.

And that just encouraged me to write more. And I, I am not particularly skilled at poetry, and I'm really honest, I don't love reading poetry, but I decided I like the structure of poems. And I Picked up a pen and tried to write a few poems. I don't think my poetry is particularly good or particularly musical or the right words, but I do the challenge of trying to find the right words to condense into a particular structure to convey a certain idea.

And that idea really shot back to relatability and I started writing some short haiku, some tankas and a couple of other poem forms about my anxiety, about not so much the eating disorder, although I have written a couple of essays about the eating disorder, but just the way I was feeling in the world.

And even if nobody reads them, it felt good to get them out. And it did feel cathartic to get it out. And I haven't written poetry in a little while, but for a couple of years it was really an obsession of mine and I did get some good feedback and there were people who could relate to some of the things that I wrote and some of the metaphors that I used for my anxiety.

And for, since that. Point in time, I have started a peer support company with a couple of Coast Guard veterans. Even though I've given up on myself in terms of therapy helping, I do feel better just not by not struggling so much to try and get better. That probably made me feel 10 percent better overall, but I do realize there's a need for

More health care, mental health care workers and as a component to any sort of a treatment plan peer support really resonated with me because there's evidence that shows that it works. Look at any. Substance abuse group. That's the strength in it is sitting around with people with shared experience, but it gets back to my writing too, which is relatability.

If you don't feel like you're the only one feeling that way, or you're the only one with a, an addiction, or the only one who's experienced sexual trauma, and you can't tell anyone about it, but then you're in a room with people who have stories that are remarkably like yours, who feel remarkably like you do.

Who who went through the same journey that you're going through. That in and of itself has a healing aspect. When I had the opportunity to start this company called Mindstrong Guardians earmarked towards the Coast Guard and Coast Guard people fall in the cracks between Department of Defense and first responders.

So many folks are traumatized and don't get help. We. We felt we'd found a niche, and that leads me to today.

Leafbox: Steve, could I just interrupt you? I want to talk about your poetic forms and your kind of nomadic lifestyle. But I want to go back to when you were after college, why did you just impulsively join the Coast Guard?

Was that an escape for you? Or what were you looking for? Were you looking for? I'm just curious.

Steve: I think I had romanticized the Coast Guard, Robert. I grew up outside of Austin. The Coast Guard Academy was in Connecticut. And There was nothing complex about it. I got my hands on a Coast Guard Academy bulletin, the front of the bulletin being the kind of booklet that describes the Coast Guard Academy to potential applicants.

And the front cover was the Coast Guards has America's tall ship the Coast Guard Cutter Eagle, which is a three masted barb. And it's a sailing vessel. Very old school and it looked really cool to me. And I had spent my summers working. near my hometown in Concord, Massachusetts at a place called Minuteman National Historical Park, the old North Bridge, but they also had the homes of Emerson and Hawthorne and places where Melville had written.

And I really got, and Thoreau and I really got into their writings and the idea of this. The ship that looked like it came right out of, to me at that stage, Moby Dick really appealed to me. And that's as deep as it got. I thought to myself, I'm going to go here. This is a cool school.

I'm going to have this maritime life by I grew up really enjoying our, the family's annual trip from the suburb to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the seashore. And part of the reason for that is the two weeks a year, my family was on Cape Cod and we were rigid and religious about going there, nothing bad ever happened.

My, my aunt and uncle were there. My cousins were there. My dad didn't drink. He hung out with us people didn't fight. They loved it. And I just associated. Even though I wasn't an ocean going guy and didn't have that background, I associated those two, two weeks a year on the beach with a calm serenity that I didn't have the 50 other weeks of the year, the 50 other weeks of the year.

I was anxious about, what's my dad going to be like tonight. I don't want to go to school tomorrow. It's one thing or another. And then I'd have this two week long exhale. And for some reason, I taught that to the Coast Guard Academy. So I applied for the Academy and I didn't get in, which was no shocker.

I didn't have great grades. But I kept that idea in my head and after graduating from UMass, I thought there must be another way in and there was so I drove myself to a recruiter in Boston and submitted an application and, Lo and behold, they accepted me and the acceptance wasn't a deeply thought out thing.

It was just, I'll have a job and I won't have to live at home. And that's that it'll buy me a few years time because there was a three year active duty commitment after you got out.

And I thought this is what I need. Otherwise, what am I going to do? Just, live in Boston all my life, or I had no plans, no aspirations, no nothing.

So this was something. Yeah. I'm glad I took it, but that's as deep as it went.

Leafbox: Steve, one of the essays that I really enjoyed was, maybe I have a bias too, I, I've interviewed another author who was a Coast Guard vet, and they're the forgotten branch, like you said, of the military, but one of the things you wrote about was your concept of moral injury in the Coast Guard and across I guess government employees and all branches of, employees across all groups and organizations. Could you expand on what you mean by moral injury and maybe some of the personal experiences you had during the Coast Guard?

Steve: Absolutely. I'm glad you brought up moral injury because.

Moral injury in general is not something that most people think about when they think about trauma. And when they do think about it, they think about the most obvious examples of moral injury. Moral injury is basically having to do something that is counter to your personal values. And having to do it, when I say that, as A matter of carrying out your responsibilities, which in public service can happen quite often.

So the first place you go with that is you teach people. And I think people inherently know that killing other people or hurting other people is wrong. And suddenly you train somebody, whether they're in the army or the Marine Corps. Maybe whatever to kill other people and you put them in a position where they are, that's their job to kill other people and they end up killing other people.

They have done something essentially at cross purposes with their internal values and that creates a conflict which in and of itself can develop into trauma. There are other ways that moral injury can occur, and the one I've seen most often with Coast Guard veterans is search and rescue, and my role was not being out on a boat, pulling people out of the water.

My role was basically planning searches, approving search areas, figuring out What resources to send, but most of all figuring out when you had to suspend or end a search, not having found the person you're looking for and to tell the family that you're suspending the search which I've had to do three times in my career.

And I've, plenty of people who have done it much more frequently than that, but you remember every time. And that there's a huge vulnerability to moral injury in. In that sort of work, because you feel like I am in a life saving organization, I joined the organization because I want to save lives, at least that's part of what the Coast Guard does.

And here I am telling somebody that not only have I not saved their loved one's life, but I'm giving up.

People obviously don't react well to that. That really, Increases that feeling that I have fundamentally failed at my job. I have fundamentally violated one of my core values. I would not want somebody to give up looking for my best friend, my brother, my sister, my parent, and this guy here is telling me he's given up.

Now, when we suspend a search, we don't do it lightly. We keep them informed throughout the search process and prepare them for the possibility. But, we look at how long can somebody survive in water at that temperature? What are the odds of finding them? This search area expands every hour and on.

So you reach a point where continued searching really isn't going to yield results. You are damn near confident that you're not going to find that person. My essay was a little bit different and surprised me because it was nothing like that and just to touch on the area that really saying it scarred me or it definitely created moral injury for me, but it was such a relatively benign event that two decades later, I still scratch my head and say, why did, why does this to this day?

still make me feel emotional. And essentially, I was the, working in the U. S. Embassy in the Bahamas, which I was the Coast Guard's liaison officer there. So my job was to interact with Bahamian officials when we had essentially cross border operations going on or interdictions of smugglers and that sort of thing.

And in one particular case a U. S. Coast Guard vessel intercepted a raft of Cuban refugees in Bahamian territorial seas, so we returned those people to the Bahamas. And my job was to meet the Coast Guard ship at the pier in the Bahamas to make sure there was an orderly transfer of the Cuban refugees from the U.S. Coast Guard to the Bahamian immigration officials. Thank you very much. This particular group of refugees came in on a Christmas morning. So I was in my uniform on the pier waiting for the Coast Guard ship. Coast Guard ship comes in Coast Guard. Immigration authorities are there with their vans.

And I knew they would take these people to a detention center in the center of new Providence Island, where Nassau Bahamas is located. And eventually transport them back to Cuba. I'd done this before and it was routine, but there were, I remember there were 26 people and I, they came off the gangway of Coast Guard ship to the pier and there was a little girl, maybe five or six who had a doll and.

I was on the gangway, and she was struggling to get up on the gangway, so she just looked at me and handed me the doll, and then I helped her up, and then walked her over the gangway and got her to the pier, and she looked at me and put her arms out again for the doll, and I gave her the doll back, and then she and the rest of the people got in the van and went to the detention center, and I never saw them again.

I went home that day after that, and 20 years later, that still makes me feel sad, and I still wonder about that girl, and I feel like this isn't what I signed up to do. I didn't sign up to take this person whose family had placed her on this unsafe raft, pushed her into the water, to head to the U.S. with an unknown outcome. And suddenly she's in the Bahamas, not even her family's intended location for her and going to a detention center at age of five or six. And it wasn't a brutal detention center, but it wasn't pleasant. I had been there several times. It was barracks, basically, in the middle of the island with razor wire around it.

And then back to Cuba, where she may or may not be. Reintroduced to whatever family she had, and it just felt so out of line with any reason I had to have joined the Coast Guard or any personal value. I felt at the time and throughout my 25 years, I compartmentalize things and. desensitize myself to things like this, but that one I was never able to do it.

And like I said, I've done Mexican notifications that haven't bothered me that much. Yeah I wrote my essay on that, but I think the Coast Guard really does, as you said, is the forgotten service because people assume that, hey, if you're not being shot at, what do you have to complain about?

And I see Coast Guard veterans all the time with untreated PTSD from doing the things that Coast Guard people do which are very similar to things first responders do. And often they're 18, 19 year old people out there in the front lines, and they're either, shooting an engine out of a smuggling vessel to stop it, or they're trying to find somebody that they don't end up finding, or they find somebody after they passed away, or they find somebody after a horrible boating accident and, all of these things are traumatic in their own right, but when When you say that, Hey, I didn't sign up to come out and shoot people.

I signed up to save people and I didn't save this person. I guess that's where my story comes home to roost is I didn't save this person. I just made life a lot worse for this person and it doesn't feel good. I just didn't expect it to not feel good. 20 years later.

Leafbox: Does the Coast Guard now have the same culture? You wrote another essay about I think it's called mental personal protective equipment, the mPPE. What's the current state of like when you talk to vets at your officer level, are you finding the same kind of Moral injury and trauma that's manifesting. How are they expressing it? Or are they, alcoholism? What are the issues that other vets are really facing now?

Steve: Yeah, that's a great question. Because I think culturally there have been incremental changes, but the Coast Guard, like the other services is very much suck it up type environment always has been. It's a little less. So now the Coast Guard has created a cadre of mental health providers that are accessible.

Mental health is a little less stigmatized, but it's far from where it needs to be. And I think it's worth noting that particularly an officer in the military, and that includes the Coast Guard, we all know and refer to our careers as zero defect environments. And I knew that, and that just stokes up anxiety that you're going to make a mistake.

And a mistake is, hey, my search pattern was wrong and somebody drowned. You start to become more worried about your career than somebody drowning. The slightest mistake can end your career. And it really is your defect. So when it comes to the stigmatization of mental illness, no officer wants to acknowledge it.

And what the Coast Guard has done is created a little more access. to mental health support, but has done nothing substantial about changing the culture. So if I were in the Coast Guard right now I would never acknowledge having a high level of anxiety, never acknowledge having an eating disorder.

I never acknowledge any sort of mental illness as an officer in the military, because that is a career ender in most cases. Less so now, but still culturally, there is a fear. I'm going to lose my security clearance if I go to see, seek help. If I go to a therapist, I know a lot of what they do now, Robert and have done for years is go out privately and pay out of pocket.

And yeah, I have a good friend who is an excellent Coast Guard lawyer, but he suffers from severe depression. And the Coast Guard doesn't know this. He is on SSRIs, and the Coast Guard doesn't know this. And he has, in his particular case, SSRIs, antidepressant drugs, pharmaceuticals, and therapy.

He views them as having been life saving. For him knowledge to the Coast Guard that he is receiving therapy or using this medication because real or not, he is fearful that it would end his career and so that's one way of coping with it. And that's probably the healthiest way of coping with it. Outside of the Coast Guard, I've met veterans who are alcoholics or use alcohol as a crutch.

And simply don't seek help because we fall into that trap too, where we feel like we're sucking resources away from some young combat vet in the army. If I see a therapist at the veterans administration, and I may be entitled to do that, I am. Because I'm one of the five, six armed services now, but most Coast Guard people I've talked to when we were developing our company, our peer support company felt like I don't want to steal resources from, from the army, from the Marines, from these people who really deserve it when I don't deserve it.

And that's, and as a result, they're untreated. And when you're untreated and you've suffered trauma, you live a life of suffering. That is in many cases, unnecessary if you the right treatment. So I think in the Coast Guard, this is particularly acute, but I think across all the services, when you look at the suicide rate of military veterans in general there's no argument that something isn't happening here and it's not just.

I was in a combat area and I saw really bad things. It's that you have to move every couple of years that families are always under strain. That, it's hard enough to maintain a marriage when you're in a more stable environment. It's really challenging when one person's At home and unable to start a career because you're moving every couple of years for your career and deployments are extremely stressful where you don't see your family for, 12, 15 months at a pop.

It's a stressful existence in general. It's worthwhile and fulfilling in many ways, but from a personal standpoint it's, it can be. That's the best answer I can give.

And then Steve, you didn't do any writing when you were in service, right? So this became a post divorce liberation escape?

Steve: Yeah. It, I couldn't have done it, Robert. I utterly lacked the introspection that I needed to do. I, that I needed to sustain my marriage. I didn't, I realized that my being a workaholic was not good for my marriage, but it was a blind spot for me. I thought in the future.

And I, I don't think I would have it's funny because had we stayed married, I'd still be rather obtuse when it came to introspection. I probably never would have started writing. So it's the divorce spurred the self awareness and the self awareness spurred the writing.

Leafbox: And then what's the response? You're writing a Medium and Substack. Have you shared essays and poems and other writing with vets or how are they responding to writing as a release?

Steve: There are some vets who see my writing and it's funny because on Substack they usually come to me via email directly if they like something or something resonated with them rather than say anything on Substack directly.

But it hasn't really resonated in particular with veterans. Some of the things I write about, anxiety is universal in, in our culture anyway. It, I would say extreme anxiety, anxiety over things that you look at and you're like, why am I anxious over this, that I had to do this today when this is relatively easy to get time.

But I've also found that, if you eliminate and avoid the big things, then the anxiety is just as intense with the little things. So that's some of the stuff that I write about. But I will say I really hesitated to put anything out there about the eating disorder because of the stigma associated with men.

And eating disorders. I only recently put something out on Substack because I just got to a point where I'm like, you know what, if it helps somebody, great. If a few folks didn't know about it haven't come across it, then they can ask me questions about it. But I do feel awkward. I feel embarrassed.

I'm a guy, I'm not supposed to have an eating disorder. I even feel that way. And I've had it for 40 years. But I also realized that, you know what, if I live another 20, 30 years I'm going to have it. It's not going away. So I think I just have to come to some sort of accommodation. An acceptance of that. I'm not saying it's untreatable. It is treatable. It's tough to treat anorexia, but I've just decided that, therapies I've tried for anxiety haven't been particularly effective for me. So that's just a personal choice I've made.

Leafbox: I think, all the writers I gravitate towards and I interviewed, I think one of the main things I appreciate is when they're truly honest.

And even though you have these issues of shame and anxiety, I think it resonates that it's coming from a place that feels very genuine. So thank you. For listeners, can you give us, I don't know much about male anorexia. What does that manifest as? Is that kind of like an Adonis complex similar to bodybuilders or what does this mean? .

Steve: Yeah, that, that was spot on. There is. Another disorder, and I don't know the name of it, for young male adolescents who want to get big, so to speak. They're obsessed with getting large. For me, it was more insidious than that. And in my teens, I saw my dad as an alcoholic.

Now I look back at my dad and I'm like, wow, we're exactly the same. He was a highly anxious perfectionist like me. And like most anxious people, he didn't like uncertainty and like it's full of uncertainties and he would self medicate with alcohol. And I thought, I don't want to be anything like that.

I want to be the opposite. Right at the beginning of the running craze in the U S I decided I don't know. I was maybe 15, 16 I was gonna start running. And I started running and the reason was, so I, cause I didn't want to be like my dad. I wanted to be healthy. And then that kind of transitioned into, I'm going to eat healthier too.

And I'm going to make my own food. And then I got very strict about what I ate, not with an intent to lose weight just to with, I'm not going to eat junk anymore. In the 70s and the 80s, that was particularly tough. Everything was processed and prepackaged. But I found so I became very choosy.

And because of the running and the desire to eat healthy, which were honest and good and benign at first. I lost weight for some reason. As I lost weight, Robert, I found it anathema to, I just didn't want to gain it again. I didn't even think of it as a disorder. It was like, no, if I'm losing weight and I'm out participating in triathlons, which were evolving in the eighties as a thing.

And, I was doing five or six triathlons a summer up in Massachusetts and I was 19 by the time I really hit my peak triathlon years. And I ran Boston marathon in 1990 in two hours and 40 something minutes. And that was walking a lot the last six miles. And I thought I could really do something here.

And the weight loss, while I don't think contributing to it, probably undermining my performance. I looked at that as. Helping me excel. I'm like if I'm losing weight and I'm running sub two Boston marathons, what could I do if I lost more weight and trained more? So that is how it came on. I didn't even really think of it as an eating disorder, and it wasn't really discussed in those days.

But when I look at some of the I've destroyed every photograph I could find of myself in those days because I looked emaciated. I saw my high school yearbook picture and Honestly, Robert, I was, I'm six foot tall. I think I had gotten down to about 128, 127 pounds. I was obviously malnourished, but I didn't think of it that way.

I thought this is the path to better performance, more exercise. More strictness with my food. And of course all my triathlon heroes were eating this way. And I thought this is the way I got to go. The Coast Guard interrupted that. And somehow I got up to by my thirties, about 170 pounds.

I was happy with that. I was okay with it. I even wanted to gain more, I felt healthy. I felt good. And then. As I gained more responsibility in the Coast Guard I my anxiety drove me less or drove me away from strength training, which was the only thing really maintaining my, my, my physique to just endurance training, which eased my anxiety.

And, my weight dipped a little bit, but it was okay when I left the Coast Guard. And then, COVID comes along and I'm in the airstream and starting to feel really weak and never weighing myself because I had anxiety about getting on scale. It was either too heavy or too light, one or the other.

But I sat for a year in the airstream when I went to see the doctor about why I felt so exhausted all the time that I dropped I don't know, 12, 13 pounds from the time I started the airstream and that just re sparked the whole thing in my head. So the thing that I thought I was at least managing, I wasn't managing, but anorexia to answer your question, because I straight away from that is it's the same.

It's, bulimia is where you purge anorexia is got its purge element, but the purges exercise and calorie control. And I it's the same in men as it is in women. It's a control thing. It's an anxiety disorder. It is the, I've got no control over what's happening in the world. I can't control what's happening in my body, but it's not articulated that way.

And I think the best way to articulate it every man or woman I've talked to with anxiety with anorexia. Has, and I've written about this. I don't know if I've published the most recent one yet as two voices in their head, and I call it a rational voice, which knows what I should be doing to live a healthy life.

And the fact that I am undernourished even to this day and the irrational voice, which is. Hey you're doing fine. You're surviving like this. Why would you want to gain any more weight? It's irrational, but it wins every time. It, my metaphor is the irrational voice always ends up with it.

It's booed on the neck of the rational voice. And I, I don't know how to overcome that, but I have found that to be universal with anorexia sufferers, and they have the two voices in their head, and the irrational voice always seems to win and people who don't have it, they don't win.

Can't understand how I can look in the mirror or anyone who's under nurse can look in the mirror and feel that they are overweight. Even when your rational voice is there, you screaming at you that you are fine. In fact, you need to gain a few pounds that living a life where you're under 6 percent body fat every day.

Maybe that's why you're cold all the time. Steve, is not a healthy way to live. I have osteoporosis now. If I had been a smoker or had been somebody who ate bad foods and had a heart disease, I'd do something. But with the osteoporosis, the irrational voice just argues it away. And I'm like, no, but that came because I've been undernourished and over exercising.

And that's going to be a problem as I age. It's an irrational disease that's born of anxiety and control. And unless you're there, you can't really get it, but I will say it. It's got the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, I think even more so than depression.

Leafbox: Steve going back to your poetry, I just, do you see a parallel?

I was surprised by all the poems have very structured, you have haikus, tankas, minkas, something called the cinquain , which I've never heard of before. But all these very structured. So is that a release? How does it interact with your control issues?

Steve: It's, it's a manifestation of control issues.

It's; I'm glad you brought that up. You're the first person to actually see that. As I said earlier, I'm not a poet. I don't, I'm not particularly creative from my perspective. What attracted me to poetry and in particular to very structured poems, haiku is simple, but I'm like, wow, you have to say as much as you can say using that 5, 7, 5 syllable structure.

I like that. It's, it feeds that desire to be in control. It's a challenge and it is spot on. A manifestation and one could say you're not doing anything to, do some free verse. And it's now I don't want to do free first. I, that scratches my itch to do a haiku or a tanka and yeah, you're spot on.

It's. You call it OCD, call it anxiety, call it what you will. That's what it is. But I, I honestly don't, I've accepted it. I'm like, fine. It gives me a moment of fulfillment to get that out there. It gives me, however long it takes me to generate the poem a period of contentment. And I've come to the conclusion that, what I want to get out of life in my remaining years is as many moments of contentment and fulfillment as I can.

Because what else is there, and I, struggling to fix myself wasn't working. So writing a haiku and spending a couple of hours on it or whatever it takes does that for me. And I'm like, fine, I'll take it. If my OCD, pursuing my OCD and straightening up the picture on the wall gives me a feeling of contentment, I'll take it.

Because. Time is finite, and you really begin to realize that when I think for me, when you get close to 60, you're like, wow, there, there's a window of time here, just be as content as possible for as often as possible and accept the discontent is just a contrast. So you appreciate the contented periods,

Leafbox: Steve, maybe we could talk about, I wanted to see how you would. Free flow for prose, but maybe we can talk about your experience with psychedelics and how that maybe was the opposite of control.

Steve: Yeah, absolutely. I became interested in psychedelics during my period in Massachusetts that affixed me period as a potential cure for anxiety, OCD, is like many people you're watching documentaries about the effectiveness of psychedelics for certain mental health conditions.

But when I got to that point where I'm like, you know what, I'm just going to accept myself as I am, I still was interested in psychedelics as an experience, but I didn't want to hang my head on the idea that I'd come out of a, a trip and be suddenly cured of anxiety. That to me would have just led to disappointment.

It's unrealistic. And I actually talked to you and my big concern was trying to sort a good guide. Who would provide me with good support. I didn't want a therapist at this period of time with, because the psychedelic trip to me was about preparation. It's about set and setting.

It's about being self aware. It's about being a lot of things and not just taking some mushrooms and, wherever you happen to be and saying, wow, that was a great trip. Like you would drink a beer or something. So I found you helped me find a location in Oregon. And I hired a good guide and we did a lot of preparation and a lot of attention setting, and because I was flying from Florida to Portland, I decided to have two trips during a 10 day period.

And I self prepared, the location, the setting was incredible. And that, that was huge. I couldn't have done this in an improper location. It was quiet, it was peaceful. It was a port Portland craftsman house and the room was comfortable and safe. And my guide was with me the whole time.

And the first.

I, and it became this battle with me. It was a moderate dose of psilocybin. It was it was for, therapeutic dose, but not extreme. And I just, For some reason went into it, not really having expectations, but thinking as soon as it hit me, I'm like, I'm, it was Steven anxious, Steve, they're saying, I'm not going to let something control.

I'm not going to let it control me. I flexing and unflexing my muscles the whole time. And while I felt it was a significant event, I certainly didn't get the most out of it. So three days later, I go back. We agree on a much larger dose and I had really focused on not fighting it. The most significant experience I ever had in my life, Robert, why I couldn't articulate it to you.

It's like I was saying about anorexia. If you haven't been there, you don't get it. People who have experienced psychedelics will get it. It wasn't easy for it, but it was definitely ecstatic. It was unifying, but not in a blissful way. It was, if I had to describe it physically, it was a series of fever dreams that would start and stop with the guide's soundtrack, every new track would end one fever dream and start another, I don't even remember a lot of what was going on, but I do remember feeling so gratified that I hadn't tried to fight it, that I did feel this unification, this oneness that I.

I had what you call an afterglow for several days. On my flight home, I was talking to people at the airport bar while waiting for my flight. I don't do that. I was had striking up conversations with people. I'm a good flyer, but I don't like turbulence. When the plane hits turbulence, I get anxious about it.

Plane hit a lot of turbulence in the way home. It didn't. latest, it was just this acceptance. What happens for the next week. I would say I was more clearly not just, I think I'm more empathetic. It was, I was more empathetic and a nicer person. Did it wear off? Yeah. But, Oh my God. The fact that a week after this experience.

I still feel this glow is just incredible. And I would say coming out of the trip that afternoon I felt exhausted and it's like finishing a marathon, if you ask me as I'm just ending the run, if I'm going to do it again, I'm going to tell you, no, never, that's, it was horrible.

Never. But if you ask me two hours later, I'm going to be like, yeah, absolutely. Yeah. That this is the most significant experience of my life. I could go into detail about what I experienced, but there's nothing really to tell that would knock anybody's socks off. I think it's just, if you've done it you get what I'm saying.

And if you haven't done it I look around at people, my peers, ex military guys who I know will never try it. I feel bad for them. I'm like you're never going to get to, wow. And I want to do this. It's something I don't want to do frequently, but I want to do it regularly. And did it cure my anxiety?

No, but I wasn't trying to cure my anxiety. It was to this day, I will be, I am grateful that I did it. And I'm interested in trying, ketamine or, Nor am I a PTSD sufferer who might benefit from MDMA, which I think shows great promise, but psilocybin and hallucinogenics strike me as just very cliché and mind opening and they are.

Leafbox: Steve, when you came back from your trip, how has it affected your creativity in writing? You keep saying that you're not creative, but you're sharing and producing. So did you feel more free?

Steve: Yeah, I think I've always felt free and open with my writing. And I think I was self aware enough that some folks said did you have any revelations when you were dripping?

And I thought, no, not really. I, I kind of have explored all that stuff, but I wasn't expecting that. Yeah, there was this I did, I wrote a poem or two about the experience. I was exuberant and excited about the world of psychedelics. I think I even talked to you about what more can I do in this field?

It, my, my writing has always been open, but I think done it, and then I wrote an essay about it on Substack Ever. I don't think, for example, I would have published. A piece on my eating disorder. Had I not just gone through that and thought, why not? Again if the idea is somebody may benefit from it.

And a few people may think less of me because of it, then it's worth putting it out there. And I don't think I would have done that had I not had the psychedelic experience. I think there is an element of a psychedelic trip that kind of, I don't want to say green lights you to be more expressive and more open, but reveals to you the fact that there's minimal downside and a lot of upside to being more open and honest.

And quite frankly, if I have one person tell me that, hey, that thing you wrote really Resonated with me or helped me. I'm like, if there were 10 haters out there, I've written some things on white privilege, and there are a lot of haters who have gotten back to me on that. But 10 haters to one person saying that you helped me.

I'm like a score, if I can help somebody, then it was worth putting out there. So I think it just pushed me over the edge, Robert, where I felt comfortable on that. In writing about the eating disorders and putting it out there.

Leafbox: Do you also, I think, some of your writing I'm curious about, you have a lot of animals in your poetry.

Do you ever think about that? Or, there's a psychedelic parallel. Some of the the tropes of psychedelics, the coyote. So I'm curious if there's any, what's the use of animals in your poetry and writing?

Steve: The animals and the most frequent one I use are actually just literary metaphors that resonate with me. That that no one would be surprised that, a coyote, even if it's a relatively benign animal. It's it's, it implies a threat. For me, the raven and the blackbird are the animals I go to the most in part, because I do the of Edgar Allen Poe. And of course, he's, most famous for the raven, but the raven struck me as the perfect metaphor for anxiety, a raven circling over your head and digging its talents into you the blackbird.

Struck me as a perfect metaphor for depression. I can't tell you why, not really, the origins of these metaphors are not in, in psychedelics as much as they are in just starting out with a literary interest that I fancy in terms of being great ways in my head to articulate an abstract idea. And I don't know if everybody gets it, the Raven being a metaphor for anxiety is a way to make anxiety physical and real.

And they're

obviously a good way to to express anxiety. But the raven, I think works and it works for me. And I've often wondered, Robert, I'm like, I wonder if anybody even understands what I'm putting out, not because it's particularly complex, but just because it's particularly personal and people may not, I think the poem you referred to with the coyote was serenity, where I was describing a benign, serene walk or something like that.

And then the coyote appears. I'm like it's, That's the uncertainty of anxiety, even butting into that moment and always around the bend, like what's going to happen now,

Leafbox: What's paradoxical is all of those animals are also quite free, right? And then going back to what you said about joining the Coast Guard, there's an element of that freedom in the ocean, the sailing, the kind of, And I think you have another poem that I enjoy called Quietus this about good sailing.

Yeah. Yeah. And it seems like there's a, you're always, I don't want to personalize it or psycho Freudian read it, but there seems to be an element of desire for freedom and exploration. And the coyote itself is an animal that's quite stoic and free from exploring the West, and the Raven as well.

Steve: They are. And you're, Your insightfulness is pretty remarkable because throughout my period of time working with a therapist several years ago, I kept telling the therapist, I'm like, the guy I want to be is the guy who just, I want to put on some weight. I want to relax a little bit.

I want to smoke an occasional cigar, a little vice that I like. I don't want to worry about everything. I ride a motorcycle now. Why? Because I feel a sense of freedom on that motorcycle, a sense of happiness and contentment on that motorcycle that I don't get any other time of the day. While I say I've accepted my anxiety, I have because I'm tired of struggling against it.

You're spot on and I hadn't really thought of the freedom of the animals that way, but the guy I want to be is, I, you look at motorcycle culture and yeah, there's the outlaw motorcycle culture, but there's also this, Motorcycle clubs originated not to break the law, but just this people who just didn't want to be tethered.

The way I live now, I can pack all my belongings in a Subaru hatchback. I don't own stuff and that's by choice. But there's an element of, I'm struggling to be this guy who is that freak coyote, but also burdened with this anxiety that, that lashes me to a routine that is predictable and secure.

Leafbox: You know what? It's a contradiction. Yeah. One of the freeing things that interests listeners is that you told me the story about grave buying and how that might be an act of freedom.

Steve: Yeah. Yeah. This is something that most people don't understand. I referring back to earlier in our conversation when I say Cape Cod was our vacation place where nothing bad ever happened.

There is that town on the Cape that we. We always visited Brewster, Massachusetts. I got it in my head that, I want a green burial. I articulate this to family and friends who I brought into the conversation as I just don't want to be a burden. I'm a single guy with no kids.

And if something happens to me, I don't want it to be a pain in the neck for anybody to have to deal with it. So that's why I'm doing this. But the real reason I'm doing it is because I'm picking my place. And I bought a, the only real estate I own is a 10 by 10 plot in an old sea captain's cemetery in Brewster, Massachusetts on Cape Cod.

And it gave me such a feeling of happiness to do it and they're like what that's, we don't talk about that in, in our society. But for me, it's no I went out this summer, I was up visiting and I went to see it. And it made me happy to know I had it. And the gentleman who I who's on the cemetery commission said, if there's a stone cutter in town, this is Cape Cod's old school stone cutter who can, do a tombstone for you if you want it.

And I'm like sure. I, why not design my own tombstone? And I hate to admit, I paid a lot of money, like 10, 000 bucks for an old colonial slate tombstone. And I am in a joking way, using an image from Poe's poem the Raven on that tombstone. And a Raven. And the word nevermore, which anyone who's read the poem will understand.

And, then my information and this stonecutter is going to put it up for me. I've told very limited people that because people really think it's over the top. But again, my, my family members who would be left handling it. I'm like this way, exactly where it is and you can, it just makes it easier for you.

But you, I am serious in that. I'm going to have a small celebration of life party, for myself at that location next year with that tombstone up. It might be just me and my sisters or my niece, or, the folks who gather down there every year.

But I thought what's the point of not being there for that? It, there is it's a place to rest and I don't mean this. And I tell people this, I look at death as a. When I'm feeling particularly anxious as there'll be an end to it, just like I opened my eyes during the psychedelic experience when I was getting fatigued.

I'm ready for it. And then I saw my guide there. And I'm like, we talked about this. It does end. Don't panic. It will end. And right now you want it to end because you've been at it for six hours or so. And I look at death the same way. There's an end. I don't look at it. It's not a suicidal ideation.

And that's, if I tell anybody that, Robert, that's straight, that's the place to go. Is or you're gonna hurt yourself. I'm like, no, I'm not gonna hurt myself. It just calms me down to know that there's an end. You And I don't want to struggle like this forever. So yeah I'm a member of a Swiss organization called Dignitas, which performs assisted suicide.

My fear is Alzheimer's, like if that hits me and I'm still cognizant, but diagnosed that to me is a relief. I'm like, okay, I feel better. And I am, as I said earlier, trying to find ways to feel more contented. And I'm like, I've taken care of these things. Part of it is I'm on planner.

That's what anxiety does. But there is an element of fulfillment in doing these things that is indescribable. And I it's just so out of bounds for what we can talk about in our culture that it's hard to really describe that to people without them thinking, Oh, you bought a grave and a tombstone and you signed up for this Dignitas company and assisted suicide and people just assume the worst.

And it's no, this is the best. This is the best. I hope I live another 30 years if I'm not lucky. That's my plan. But if something intervenes, I'm okay with this. I guess the way I put it is I'm terrified of dying, but I have no fear of death. If that makes sense. The moment itself is.

Creates some anxiety as it should. But the after part of it, I'm like, no, it's, call it what you want, call it a Buddhist Nirvana. But yeah, that's I've done that. And I'm just waiting to see what the stone cutter comes up with.

Leafbox: Steve, you said for positive reformation that you want to live in another 30 years, what do you imagine filling the next 30 years with? You have your peer support group you've started and what other projects do you want to focus your attention on more writing, less writing, more trips. So what do you imagine for the next 30 years?

Steve: And I'm just putting that out. So I know one thing I learned when I left the coast guard, which might be a surprise is I will never see that my schedule was very structured there, and I think that was helpful.

To me in anybody's schedule at work, you've got to be a place from this hour to that hour. And then if you lose that structure, a lot of people are lost. I thought I'd be one of them, but I'm really, I'm not I will not cede my schedule to anybody else, but what. And, but I think I did struggle a little bit with when I left the winery, which was a full time job I was in the airstream.

So that occupied a lot of my time, but there was this notion of, what are you going to do for the rest of your life? But I've resolved that. And I think I'll write about the same. I'll be at that same level of productivity that I am right now, but I dabble in a variety. You and I've talked about this small businesses that I think matter.

I've done some venture capital in areas that are meaningful to me. Climate and healthcare. I am always looking for opportunities to do work. That's interesting to me. I'm helping a buddy in town with a brewery startup, a distillery. Didn't have to do that. I just find these opportunities to occupy myself and I don't get so hung up on having to leave some sort of a legacy.

It's just what I pursue, the things that make me curious right now. And the things that make me curious right now may or may not make me curious in a couple of years. I've got motorcycle trips planned. I might go back to the Airstream thing when I can't ride motorcycling. I've got these things laid out that will occupy me, but none of them are of the traditional.

I gotta go back and get a job, so I'm not bored all the time. I seem to find an endless number of things that are of interest to me. And I'm not really thinking out that I glance at it every now and again, 20 to 25 years, but my days seem pretty full and I just don't worry about it. I think I'll be in this house in St.

Augustine for the next two years. Where am I going to go after that? What's the next Airbnb going to be? And. And that's, in fact, I was out in Portland for the psychedelic experience and I thought how it is freeing knowing I could come up with Portland. I want to. Nothing's binding me to any particular place.

And these it's future thinking. Yes. But not 20 to 25 year future thinking. I don't have a 20 to 25 year plan. And that to me is way less overwhelming. It's just a loose structure for the next couple of years. And I think the thing I just occurred to me as I was saying that is there are elements in my life that are so controlled that it's, calcified my daily routine.

And then there are areas of my life that are so impulsive that it's it's 180 degrees from my calcified day. And I'd be at a loss to explain why except one is a reaction to the other.

Leafbox: It's just coming back to the animals. I just keep thinking of the coyote. Steve, how can people find you? What's the best way for them to read your essays and connect with you?

Steve: I would love more free subscribers on Substack. I have no intention of making any money on Substack. And I think you just have to type in my name which, Is Steven with a P H and Chamberlain C H A M B E R L I N. And do a search for a guy with a beard was my photo.

And I would also love anyone who subscribes to be open and free about commenting or criticizing or starting a conversation I'd like. Some more engagement on some stack for no other reason than I like to engage with people that way. And I'd like to know I'm helping people or what I could do better.

So sub stack is really the predominant location for me. And the easiest way to find me and DM me if you're a bit interested in that.

Leafbox: Great. And Steve, anything else you want to share?

Steve: Gratitude that you asked me to do this, Robert, I've always looked up to you and considered you a role model and a mentor and so appreciate.

And I'm honored that you felt it was something worth taking your time today to talk to me.

Leafbox: No, no, I really appreciate the like raw and honest writing that you're doing. And everyone's on a journey, so I appreciate your struggle.