Interview: Kana Chan

Kana Chan is a Canadian living in Kamikatsu, Tokushima, Japan’s first “zero waste” village in rural Japan. We spoke in detail about her homestay program, tourism, the urban vs rural, dating, language learning, dialects, zero waste and more.

Kana Chan is a Canadian living in Kamikatsu, Shikoku which is Japan’s first “zero waste” village in rural Japan. She records her daily life at her substack at Tending Gardens and runs inow (いのう)an educational homestay program that connects visitors with longer work stays in Kamikatsu along with another two partners. We spoke in detail about her homestay program, tourism, the urban vs rural, dating, language learning, dialects, zero waste and more.

Leafbox:

Kana, thanks so much for meeting with me this morning. I was just talking. So me and a friend were listening to your podcast. She's from Argentina and she used to live in Japan

Kana:

Oh, nice.

Leafbox:

... and we were listening to your podcast, we were looking at your blog, we were looking at your substack, we were looking at the town, looking at some other videos. We spent a few hours with some of your content. But one of the things maybe I can start with is like, where does this inow program even start with?

Kana:

Yeah, so it's actually pronounced eno(いのう), so it's also yeah, it's a bit confusing because of the English I-N-O-W, but inow stands for return home in the local dialect here in Kamikatsu, so it's like eno. So INOW started as actually as an internship program. And so there was kind of needs within Kamikatsu for labor. I mean there still is, as in during certain periods of the year when harvests are busy, there's more hands that are needed for harvesting.

And so it started as an internship program where we would invite people to come work and do kind of a work exchange. They could stay and have room and board for free and then exchange, just help out with harvesting tea or working in our cafe. And then the pandemic hit and then we had lined up all these people for internships or well, work exchanges and then it was a moment to reevaluate.

But we realized that in reflecting on why the internship was so meaningful to us and meaningful for the people who came was because it was an opportunity to integrate into local life. And so we thought, okay, well could this be, it seems like people are interested in coming and it seems like there's maybe, there's still the need to have people help out, but we could make this into a program. And then given even more kind of integrative and immersive experience into Kamikatsu and daily life in the countryside.

So that's how INOW started and so then we actually started in the middle of the pandemic in July 2020. And I mean of course that meant that very few people could come, very few people were traveling, but travel within Japan was still pretty acceptable. And so it kind of weaned and waxed, but we had very few people, maybe several guests a month.

But that worked out really well for us because it helped us to work out what we liked about the program, kind of a suitable duration for the guests and thinking about different offerings we could offer. I think the main thing for INOW was there's no program available in English. There's no resources available in English in Kamikatsu. That's reflective of most of the countryside. And so we saw this as an opportunity to also bring in English. And so we help other restaurants or other tourism spots with English as well. And so we're a team of supporting businesses in English, but our main business is INOW, just this home stay program.

Leafbox:

So maybe we go back one second and maybe you can just, I'm familiar with Kamikatsu, but maybe you can just give us a one second or one 30 second spiel on why Kamikatsu is famous and why people should come think about it.

Kana:

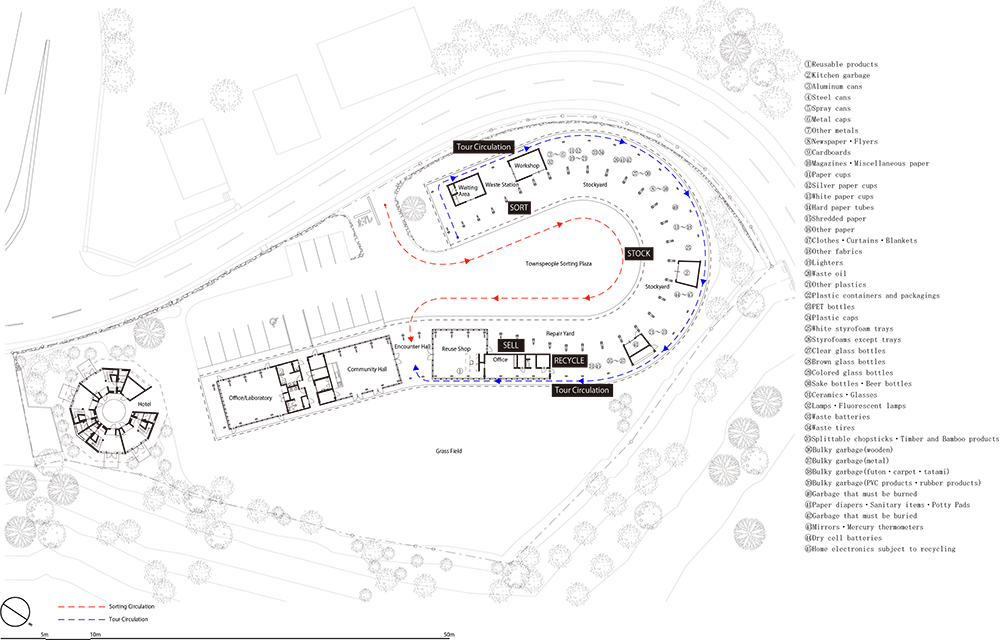

Yeah. So Kamikatsu is famous because of the intensive recycling program that was started over 20 years ago. In 2003, Kamikatsu declared itself the first zero waste village, and so zero waste is not what we think of maybe typically in the west as producing zero garbage or a tiny jar of garbage, but instead zero waste means diverting all garbage from incineration and landfill. And so that means composting was required.

And then the categories of separation are now 45 categories. And it seems quite intensive, but once you kind of get used to the system, it's not that yeah, it's not demanding. So that's why it's famous as the first "zero waste village" But I think from our perspective, that was just really one piece of Kamikatsu. And for us being in the countryside is very special. And being connected with people who have traditional wisdom, know how to make things with their own hands and do things for themselves, make things as well. That was also a really important piece to us. So through INOW we felt like we could not focus just the image of Kamikatsu on this recycling system, but so much broader and introduce people to countryside.

Leafbox:

And then going back to your project at INOW, were you guys the founders of the workshop program or the trainership program or was there a government relationship? Maybe you can walk me how that started.

Kana:

Sure. So it's a private business. We are three co-founders. Myself, another Canadian called Linda Ding and a local who is actually born and raised in Kamikatsu. Her name is Terumi Azuma. She runs a zero waste cafe in Kamikatsu. The cafe is nine years old. And it started because Linda was working part-time at the cafe and then the internship was born after that. And then the trainee program shortly after that.

Leafbox:

And how did you connect with the Japanese partner? Did you meet her in college or how did you first meet with her?

Kana:

Oh, no, no. So Terumi was born and raised in Kamikatsu. She left for university and then worked for a bit in Tokyo and then did what's called a U-turn where people from the countryside return to their countryside home. And so she did a U-turn and returned to Kamikatsu. Then she opened up her cafe.

And then Linda, the other co-founder, came to Kamikatsu as a tourist, as a tourist just to visit. And then really fell in love with the nature in Kamikatsu. So decided to stay and then she started working part-time at the cafe where Terumi works. So then that connection was created then. And then I came later, about a year later after Linda had been working in the cafe and I connected with Linda online because I was really, I saw her on, I think it was a news piece and she introduced herself in English as a Canadian in Kamikatsu, so I was very curious and then I reached out to her. And then, so then that's how I met her through Linda.

Leafbox:

And then you have Japanese descendancy or not? Or you're Canadian Cantonese?

Kana:

Mm-hmm. My mom is Japanese and my dad is from Hong Kong, but I was born and raised in Canada.

Leafbox:

And then prior to, what was your Japanese level at prior to moving to Kamikatsu?

Kana:

Yeah, so I spoke with my mom in Japanese, but it was pretty conversational. I did some school in elementary school, like a Japanese after school program. And then I studied a bit of Japanese in high school, but I had never lived in Japan. I was living abroad but had never lived in Japan, so Kamikatsu is the first time living. So I would say speaking, not fluent but fine for daily life and writing as well is, it's not fluent either, but also okay for daily life.

Leafbox:

Got it. And then do you speak Cantonese as well?

Kana:

I do yeah, but conversationally and that was also because of my dad.

Leafbox:

Great. And then would you say your Japanese side or Cantonese side is stronger or both kind of equal? I'm just curious.

Kana:

Yeah, no actually because my mom wasn't working when I was young, so she was at home so she would speak to me in Japanese, so that comes a little bit more intuitively because she was just home more and now living in Japan yeah, it's definitely much stronger, my Japanese than my Cantonese.

Leafbox:

Great. And then could you tell me a little bit about the dialect you said that is prevalent in Kamikatsu? How is that different than main Honshu Japanese or the mainstream Tokyo dialect?

Kana:

So I guess there's yeah, there's just many, many dialects and many different ways of speaking. In Kamikatsu we have, well in Tokushima, the prefecture I'm in, we have a dialect called Awa-ben, so Awa, it used to be the kingdom where the current Tokushima is. So Awa-Ben. And then on top of that there's what's called Kamikatsu-ben. So ben is dialect. And so then there's kind of more specific words that only people in Kamikatsu used, but I would say generally most people speak a version of Awa-ben and Tokushima being very close to Kansai. Osaka-Kobe also speak a little bit of the Kansai-ben.

And so actually many of the elderlies I find very difficult to understand. Some of the real, real locals, I could probably only understand 20%, whereas if someone was speaking kyojungo the kind of-

Leafbox:

Tokyo official, yeah.

Kana:

Yeah, standard Japanese and it would be no problem. And people also don't speak as politely, so people are pretty casual in how they speak to each other.

Leafbox:

Great. Well I think one of the interesting things about your project is you moved from Canada and where were you living in Canada?

Kana:

I was living in Vancouver.

Leafbox:

Got it. So you went from a major metropolis to living in rural Inaka(countryside) kind of countryside Japan.

Kana:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

I mean obviously that has pros and cons and how your podcast explores some of those. Maybe you can, I mean I don't even know where to start. Maybe you can start with your culture shock. How was that for you?

Kana:

Sure yeah, actually before moving to Kamikatsu, I was actually based in Bangladesh. So I was based in Chittagong, the second largest city in Bangladesh. So actually yeah, it's a contrast coming from Vancouver to Kamikatsu, but even more from Bangladesh to Kamikatsu. So I would just say the kind of abundance of nature, it's like a positive shock.

And I think another culture shock was just I had never lived in somewhere where the sense of community was so prevalent. I think in cities you kind of fall into niche circles where your hobby kind of draws people together. I was in a group for running or yeah, but here just daily life and work overlap. And so for better or for worse, people are very close knit even though we're in the mountains and so it's not a... Many other Inaka, maybe the people are living or Inaka countryside, maybe people are living a bit closer together.

But here people are quite spread out in the mountains. But still, when it's time for a certain harvest, people just kind of congregate and come together. And a real sense of people just looking out for you, the people who aren't necessarily related to you via work or hobbies or family.

Leafbox:

What did you study in university?

Kana:

Yeah, I finished my bachelors in business administration and then I did my master's in sustainability and tourism management.

Leafbox:

Oh wow. So maybe we can start with there. Clearly the Inaka of Japan has demographic issues. I mean half of Japan entirety is facing a major demographic issue and they don't really want to allow immigration. What do you think of just the role of tourism, I guess, in trying to create some sustainable economic option for these small towns?

Kana:

Yeah, it's been interesting because very, very recently the Japanese government has allowed pre-pandemic visa regulations, which means that most countries can come to Japan now visa free. And it's great news for us, I think as a small business and our main priority has been welcoming foreigners. But I've heard a lot of, not particularly in the countryside, but my friends in Tokyo or the bigger cities seem to be quite averse to tourism. And I think just feeling the negative repercussions of mass tourism has been really not something that they're quite positive about.

And I think in this very two and a half years of very tight Covid and foreigners allowed into Japan was quite strict and so they felt quite free from the burdens of mass tourism. I think that if you think about sustainable tourism, I think redirecting the flow of tourists out of the big cities to countryside, but then it's not so simple as just putting them into the countryside.

I think it requires a lot of investment in different infrastructures that support tourists who could come on their own. I think that people don't really go through travel agencies and so there's a sense of autonomy that's needed, but for that you need the resources available.

So I think that the kind of model we set up and as well in the countryside, I think it's difficult to just show up and then expect to feel like you can integrate or have these experiences. So we do really see our businesses, it's a very, very small project, but if it could be replicated in other countrysides, then I think it could be really beneficial in offsetting maybe some of the flow to only cities.

Leafbox:

I was going to ask about some of the businesses that have set up in the town, I saw that there's the brewery, which is kind of a, and then there's the coffee shop and the hotel. Do you guys have a business council or how does the town address itself as the economic development? I'm just curious how that works. Do you deal with the city government or how is that processed?

Kana:

Yeah, I personally am not in the city, or sorry, in the business council but Terumi is, and they get together and discuss, but it's interesting because there's no tourism council, but a lot of business comes from tourism. But there is a business council and they discuss yeah, they discuss business flow, business activity, profit, and also local ventures trying to create a space where new companies could enter Kamikatsu.

Leafbox:

... has there been any support from the federal or municipal governments? I'm just curious on structures.

Kana:

Yeah, yeah.

Leafbox:

You're pretty out there. I mean it's far removed from major city governments or whatnot, so I'm just curious what the resources are that are given to the town.

Kana:

Yeah, I'm not actually not sure exactly what kind of national budgets they receive. There are definitely something, but I don't know the details of that.

Leafbox:

And then is the town trying to attract more what you said U-turn type of entrepreneurship or more new residents or what's the plan there?

Kana:

Yeah, I think this is true of most countrysides in Japan, but there's this kind of term for U-turn where you leave your hometown but then return to your hometown. And then there's I-turn, which is when people from the city move to the countryside and there is this government program that supports these I-turns.

And so if you decide to move from the city to the countryside and they have job postings that are given by the local businesses. And if you work with that company, you can have your salary subsidized from the government, and then you have other additional benefits like car and rent support. And that comes from the government, not from the business who's hiring you. So there are these kind of programs, and I know that in Kamikatsu we have about, I think less than 10 of these government-supported work programs.

Kana:

These are only for local, as in only for Japanese people.

Leafbox:

In this town. What was the main reasons for those U-turn or I turn people to return?

Kana:

Yeah, yeah. I think about Terumi and for her it her connection with her hometown, her mother was very instrumental in setting up the zero waste system and so she felt like her mother also passed away around the same time she came back to Kamikatsu. So for her it was important to carry on the legacy of her mother. I know for others who are also back after being away came home because of familial ties.

Leafbox:

Do you think there's, do you know what the LOHAS kind of lifestyle is in Japan?

Kana:

Oh yes, yes, yes.

Leafbox:

I mean that's kind of a consumerist version of ecological life. Do you think there's a disenchantment with younger Japanese people with their traditional economic model or not?

Kana:

I do think that some people move to the countryside in kind of an escape from the economic pressures or the work pressures of the city. I don't think it's a case for everyone who moves to the countryside, but I do think that people are seeking some sort of maybe alternative option to work, to health, to life, and so in that sense, maybe a little bit connected to LOHAS. Although yeah, I'm not sure. I do think that you accept so many differences by moving to the countryside, so you have to be aware of that reality to move.

Leafbox:

Do you think people in the countryside are more open-minded or closed-minded than in the metropolis?

Kana:

Yeah, and I'm only speaking of Kamikatsu because I know that many, many countryside are very different. I think that it's not necessarily that people here are close-minded. I think that sometimes people can be quite just unaware. And I think that their world, especially the elderlies who are only born and raised here, some have never left Kamikatsu. And so their world is just smaller.

I don't think they're necessarily close-minded because we do bring a lot of our guests to local people and there's a lot of curiosity and a lot of interest in learning about who they are and where they come from. But I grew up in Canada and I grew up in Vancouver where it was just so multicultural. And in that sense there's a different concept of open-mindedness. You're just receptive to different cultures and ideas.

And maybe that receptiveness of new ideas is not embedded into the fabric of Kamikatsu, but there is curiosity and there is a warmness. And I think that most people who come here either as a tourist or as someone who moves here, especially if someone who moves here is quite embraced warmly.

Leafbox:

Are there any foreigners other than you and your partner living in the town?

Kana:

So Linda yeah, just a business partner, but Linda is the only other foreigner. My sister recently moved to Kamikatsu, but she was only here for a year and I think we're the only three.

Leafbox:

Interesting. I've been to Japan many times and I personally like the Inaka more than Tokyo. I have a daughter.

Kana:

Come to Kamikatsu.

Leafbox:

Yeah, no, it looks great. I have a young daughter and we went, the last time I was in Japan, before Covid, we were breastfeeding, my partner was breastfeeding, and in Tokyo you would get the most horrendous kind of disgust and it's just a very anti-natal place. But we went to Naoshima and Teshima, these very tiny islands.

Kana:

Yeah, Teshima yeah, yeah. Not so far from here.

Leafbox:

Yeah. And the grandma's there were literally grabbing my daughter and giving her baths and giving us suika and sharing watermelon, inviting us to drink Shochu and we had no issues as foreigners. I speak some Japanese, not fluent obviously, and they were so receptive and kind to us, whereas in Tokyo, literally, I mean obviously I have friends from Fukuoka, so the more south you move, it becomes more relaxed and friendly.

And I'm calling you from, now I live in Hawaii. I used to live in the mainland of the US and Hawaii's kind of a different country entirely than the United States. So even here I find the rural people a little bit more open. They're less judgemental. So even if you went to Vancouver and San Francisco, there's a certain inflexibility of being.

Kana:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

So I was just curious if you've become more of... Vancouver, San Francisco, New York, there almost, there's a homogeneity to it, whereas your town Kamikatsu, there's the local dialect, the local tea. You were talking about the an-ban-cha and there's a lot of local cultures. I'm just curious if you've become more interested in the local versus kind of the global.

Kana:

Yeah, that's so interesting and sorry to hear about those experiences in the city, but I could imagine that being the reality. And I'm glad that they were counter to such more positive experiences in the countryside. And I guess that's also really what we want to show because it's so hard for us to tell that without experiencing it for themselves. And so that's definitely the experiences we want to share with our guests.

I think definitely being in somewhere like Kamikatsu with such rooted traditions, it does feel yeah, I'm going from something very macro to something very micro and very honing in on these very specific and unique traditions. I don't feel at all very rooted to Vancouver probably because there wasn't that element of tradition and I thought I would always need somewhere with a lot of culture. I still do feel that, but I'm okay with that being a trip and for the base to be here in Kamikatsu.

So Kyoto's not too far, so I do enjoy, still enjoy the culture and the art and that's really not here in Kamikatsu. We don't have konbini, we don't have movie theaters, we don't have much. But then yeah, counter to that, it's nice to be able to explore these traditions with local people who have been practicing them for a long, long time and intergenerationally.

Leafbox:

On one of your podcast you talked about Nakamura-san. I think she's an elder. Maybe you can just tell me more about her.

Kana:

Yeah, so actually Osama Nakamura-san, so a he. He has been living in Kamikatsu for over 30 years and Nakamura-san was kind of a regular Japanese person in the sense that he grew up in the bubble era, had a salary man job, and then decided that he wanted to explore the world and leave Japan, and so he went on a 15-year journey kind of around the world with a lot of the latter part of his journey being based in Nepal.

And when he was in Nepal, spent time with tribes, spent time with Buddhist monks, and then learned a lot of craft, particularly wooden craft where you, it's called mokuhanga in Japanese, but you carve wood and then you create block prints with the wood, so learned that craft and then was connected to a Japanese community in Nepal and then decided to return back to Japan.

He wasn't sure where to return back to and within that Japanese community in Nepal connected with someone who was local to Kamikatsu. So he moved here and started his life, but he took a lot of inspiration from his time abroad and from people in Nepal. And then his house is just set up in a way that he consumes very, very little energy.

I think his energy bill a month is one light bulb of 400 yen and otherwise he cooks with wood and he makes most of his own food. He doesn't have a car, so he drives. And so this kind of lifestyle for us is very yeah, it's not very accessible for a lot of people, but I don't think the point of bringing our guests in Nakamura-san is for people to walk away thinking they need to only cook with wood, but to rethink how we consume and why we consume and get inspiration from how he lives so integrated with nature.

Leafbox:

One of the questions my Argentine friend had was, why do you think in Japan there's no culture of upcycling or recycling at a massive scale? So if you go, every major city in the US has people using bags to their laundry, not their laundry, their shopping and whatnot. But in Japan there isn't that culture and there's so much plastic wrapping, so much. So I'm just curious why you think that is and why there's that disconnect when there's the slow LOHAS kind of movement, but then the consumeristic... I'm trying to figure out where those conflicts come from.

Kana:

Mm-hmm. I think if you really look back a little bit further, Japan did do a lot of upcycling, recycling and using things that were able to go back to the earth. Even here in Kamikatsu, you hear about local people talking about yeah, they had fish wrapped in leaves when they went to the place to get fish or everyone made their own tofu and things like this and their own soy sauce.

So I think yeah, I'm not sure where it changed, but I think that plastic became synonymous with sanitation and with cleanliness. And I think in Japan there's also a very pervasive idea of perfection or seeking things that are very perfect, and so that's reflected in a lot of the produce that's at the grocery stores and then on top of that being wrapped in plastic to preserve that.

So I think that traditionally, as in several generations ago, that was not the case. Yeah, I'm not sure why at large it's not, upcycling is not promoted, but in Kamikatsu we do have a shop that's dedicated to upcycling and recycling. And so people can bring in their used clothes or their used kimonos. We also recycle the Koinobori from Children's Day, the kind of carp stream hangers, and then upcycle those clothes to make new clothes. And local people also do craft with those things like make pouches or bags. And so that's sold right next to the gomi station or the recycling center.

Leafbox:

Do you think, this might be more of a challenging question, do you know the Aum Shinrikyo cult in Japan, obviously-

Kana:

Yeah, yeah.

Leafbox:

Do you think there's any cult behavior in the ecological kind of zero waste movement? I'm not connecting the two, but I'm just curious if the town has any kind of... Do you ever feel isolated or pressured? How are the peer dynamics work in the town?

Kana:

No, no, not at all. Not at all cult or pressure. I think some people feel pressure to do recycling, but yeah, I wouldn't say that it's pressure so much that it feels like there's no way out.

Leafbox:

Is there anyone in the town who just refuses to participate in the zero waste program?

Kana:

Yeah, a hundred percent. I would not say there's a hundred percent buy-in into the system. It was still introduced only 20 years ago and so it's still relatively new compared to locals who have been, for the most part. So before the recycling system, there was an open burning, so it was just this giant hole in the ground and people would throw their garbage into this hole in the ground and it would just be set ablaze weekly. And if you didn't bring your garbage this hole in the ground, people would just burn it in their own homes in just like these tin can things or just- Yeah, which is just crazy. And so there are-

Leafbox:

They weren't using commercial incinerator, right, to generate electricity?

Kana:

No. And so actually they purchased, after the giant hole in the ground, and they're local here who are, for example, Terumi, whose in her mid thirties she remembers this giant hole in the ground and how bad it smelled, but after that hole in the ground, they purchased two incinerators and the two incinerators were used for a bit.

But then there was a national regulation passed where there was a certain level of dioxin that incinerators could produce. And the recently purchased incinerator didn't meet this qualification, so they had to either purchase new incinerators or start shipping their garbage, but both were very costly. And so recycling was also this economic alternative. They said, "Well, if we don't produce as much waste and we recycle our waste, this could be an alternative way forward."

Leafbox:

So what are the people who aren't participating in the program like? I'm just curious.

Kana:

I think that they're just stuck in their ways of doing burning.

Leafbox:

Oh, so they're still doing open burns in their backyards or whatnot?

Kana:

Yeah, I think there are still some people who are doing this. Yeah.

Leafbox:

That's kind of interesting. At least, I mean, that makes it, at least the town have some dynamic non-cult like-

Kana:

Yeah, I think the media portrays it like that. Everyone is a hundred percent buy-in, but I don't think you get a hundred percent buy-in to anything anywhere and it's certainly the case here. And there are some people who do recycling really well and some who don't. And there's staff at the garbage center who, or recycling center who help with people who have a difficult time. But I also don't think that this is maybe the best system. I'm not sure. I think that with an increasingly elderly population, recycling into so many categories is very difficult. And so I don't know if this is more of a burden than it is kind of a positive environmental action.

Leafbox:

It's funny because here in Hawaii there's no recycling, at least, and well, there's a little bit, but it ended up being canceled because all the recycling was just being sent to China. And when China refused to accept it, and-

Kana:

Oh wow.

Leafbox:

The incinerator became the best option because the incinerator could then generate electricity. And it's interesting because some of the economic analysis can be quite complicated. Recently I read about the canvas bag actually being more environmentally heavy than a plastic bag, potentially. So it's just-

Kana:

Mm-hmm. It's actually depending on its lifespan, right?

Leafbox:

Correct. I think what's more interesting to me about the zero waste program in the town is it creates, it's not nihilistic like Greta Thunberg or some of the kind of extinction rebellion-type environmentalist. I felt a very positive community feeling from all the Kamikatsu, at least maybe it's just Japanese people are that way, they feel positive about the future even though their country has a lot of problems. So they're just optimistic somehow. The Greta image is very just end your life almost-

Kana:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

... where the Japanese grandmas seem to be happy to just take off lids and wash things and separate them into 45 categories and not really complain. Right?

Kana:

Yeah, I think there are some of those grandmas and then there are complaining grandmas who are like, "Why am I washing my plastic?" So I think it's definitely both. I think media distorts maybe the hundred percent buy-in image, but there are definitely people who find it challenging or time consuming. I mean even I do, but I don't think it's difficult, so I definitely think-

Leafbox:

One of the interesting questions my Argentine friend had when we were looking at your content is that when she had her gallery in, I think it was in Kyoto, she had her first show about trash in Japan.

Kana:

Oh, wow.

Leafbox:

And they spent six months collecting trash on the beaches of Japan and Japanese government always saying, "Oh, all the trash is from China, it's all from Korea, it's all foreign." And then what they did with the Japanese artist was identify all the trash and it was like 95% Japanese.

Kana:

Wow.

Leafbox:

So it's interesting because even in Tokyo, when you go there, there's like no trash cans anywhere, but you go to the convenience store and there's like 45 pieces of plastic per sandwich. So it's just an interesting, I was going to ask you about the concept of Honne / Tatemae.

Kana:

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Leafbox:

And if you see that in the town. For people who don't know what that is, I don't know how to describe it, but the inner face and the outer face. So I'm curious how you navigate that being a foreigner in Japan.

Kana:

Yeah. Yeah, it is interesting because sometimes I think I'm more Japanese because I grew up speaking, but then things like these concepts, I really have a hard time where reading the air, kuuki wo yomu, I have a difficult time. And I think I'm a pretty transparent person in that my inner thoughts are probably reflective of what I'm saying outside. I think it's more difficult to get to know people because I'm always wondering, is this yeah, is what you're saying on the outside, but what do you really feel on the inside?

But I think in the countryside people, you build these relationships over time and you nurture these relationships. So I do feel these kind of lines and separations crumble a little bit, but yeah, this is from a foreigner's perspective, from my perspective, so I'm not always sure that I know-

Leafbox:

Do you have any religious practices?

Kana:

No, I'm not religious.

Leafbox:

No, I was just curious because you, there's Matsuri and kind of Shinto and Buddhist Obon festivals, so do you participate them just as a agnostic or lay person then?

Kana:

Yeah, as a lay person, probably. I believe in some, I think I'm spiritual in that I think that there's some sort of higher being and there's a possibility of maybe spirits or other things, but I don't subscribe to a religion. But I do think that these matsuri and these practices are so fascinating to observe and be a part of, and so I just try to do it with as much respect but not as practicing the religion.

Leafbox:

Have you developed any relationship with Yokai or any folklore in Japan, because in Inaka there's a lot of-

Kana:

Yeah, there's a lot.

Leafbox:

Yeah.

Kana:

There's a lot.

Leafbox:

So I'm curious if you have any favorite new goblins or demons or kappa or anyone.

Kana:

I'm not super well read or into it, but I do hear about people talking about certain things that live in different forests or mountains or rivers. Yeah, no favorites. But there is a god in Kamikatsu where if you lose things, you can go pray to that God and it'll help you find your things. So Terumi lost her passport and went and prayed to that god and found her passport. And every time you find something, you have to give that god sake or some sort of offering, so that's a good God to have.

Leafbox:

Well, I was going to say is isn't everything just upcycled into the secondhand store? So you just go there.

Kana:

That's true. That's true.

Leafbox:

So the god is just working there, I guess. Could you tell me about this tea you guys drink, this fermented tea, the bancha?

Kana:

Yeah, so it's called awa-bancha, awa again because of the awa kingdom of Tokushima, and then bancha is, it's written not... Normally people think bancha comes from Ichiban, niban, sanban. It's a ranking and that ranking is used for green tea. So when the first harvest, you have Ichiban tea, you have niban tea. A bancha is a different bancha. It's the character for evening, so ban 晩(ばん), and that was to separate it from green tea because actually Bancha is harvested from the same green tea leaves, but because it's fermented, it becomes a completely different tea. So there's this kind of play on kanji and bancha is-

Leafbox:

How are they fermenting it? In koji?

Kana:

In vats. In these large... No, no, no. It's actually an anaerobic fermentation, so after the leaves are picked, and it's different than if you go to Uji or Kyoto, you have kind of cultivated tea farms and there's just rows of tea. In Kamikatsu these teas really grow quite wildly and almost everywhere. If you go for a walk and you know what you're looking for, you can find almost these bancha teas, any bancha leaves anywhere.

So green tea is harvested in April and bancha is harvested in late July, August. Once they're picked from the mountains, they get boiled. And once after they're boiled, which is quite unique as well, they get boiled and then they get rolled and this rolling kind of starts to activate the bacteria in the leaves. And then after they're rolled, they get pressed into vats, into these wooden vats and then it's pressed down with rocks.

And so double the weight of the amount of tea you picked, you put the rocks on top and then you're really just releasing all the air and it's just an anaerobic fermentation. And it's fermented from anywhere between three weeks to 50 days, sometimes even longer. And it's really kind of depends on how it was done.

And bancha was done for families only, so people only made what their family could drink. And so that's why this tea culture, fermented tea awa-bancha has not spread very far because it was done only for the family. And then after it's fermented for that period of time, it's dried out. Kind of each leave is picked because they've been pressed down, so each leave is spread out and it gets dried for about three days and then the tea is ready.

Leafbox:

Wonderful. And no, I saw on your blog you have so many umeshu and you're making a lot of local kind of products, which seems very beautiful and special. I mean, maybe for people who are interested in visiting this town, what do you recommend for them? Should they go through your program? Through private travel? What do you recommend,

Kana:

Of course, they should come through our program. No. No, it really depends, I mean, what they're looking for, everything in Kamikatsu depends on the seasons. And so if you want to do things like harvesting rice, it depends on the season, harvesting tea only summer. And I think there's a lot of nature that's very accessible to people without a guide and visiting. But I think it's those connections with local people. And if you wanted to have those experiences having tea or cooking with local people, then we've built these relationships with trust and with time. And so we built them so that we can also bring people into our lives and show them these people or these relationships.

So yeah, if you're looking for those kind of more personal relationships or experiences, then I think the program's good, but the program is for people who maybe, I think if you want to spend a bit more time and live a little bit more slower, I think that that would be a good fit, but if you are tight on time and you want to just visit the recycling center, visit some nature spots, I think it's very accessible for anybody who wants to do it.

Leafbox:

And then I was listening, we were listening on your, I think one of your podcasts, you were talking about dating. Has that been successful or not? You guys had a lot of humor on that. I couldn't catch if you did have success or not.

Kana:

Yeah, Linda is in a relationship with somebody who's actually from Tokyo, so it's a long distance relationship. I actually was not successful in finding somebody in Japan. I've actually recently connected with a previous boyfriend that we split up, but then we are back together and he's from Belgium and he's actually going to be visiting Japan soon, so I hope that works out.

Leafbox:

Nice. And for the older, I mean one of the demographic issues Japan has, there's tends to be more men in the countryside and they have kind of the Filipina and Thai wife kind of visas. I'm just curious, have you seen any of that in Shikoku or have you ever seen-

Kana:

Yeah, that's so interesting. No, I haven't seen that anywhere in Kamikatsu. I haven't been around that much in Shikoku but there are a couple other inakas I visited in Tokushima and I haven't seen that. I will mention that there's a dating, not dating. There's a matchmaking service in Kamikatsu. It's called Kamikatsu Cupid. And it's like three or four elderly ladies who provide matchmaking services, so I thought that was quite funny. They're hosting a dinner next month and I was asked if I wanted to go.

Leafbox:

Is that traditional matchmaking as in, Is that what... I'm just curious. That sounds fascinating.

Kana:

Yeah. Yeah, it's not like a gokan, which is really the traditional matchmaking services. It's kind of more casual. It's like they'll invite, they have these posters and on the poster they say, "We're making sushi rice together," but it's organized by Kamikatsu Cupid. And so if you register then they'll try to match the amount of men and female, they'll try to have that ratio, so it's a casual kind of matchmaking.

Leafbox:

No, that sounds very beautiful. That's what I was coming back to. Even with the town has what, 1,500 people or something?

Kana:

Yeah, 1,500, yeah.

Leafbox:

They still seem optimistic and positive. So just having these small things seems, you hear about some place in Ohio that's dying or some Canadian small town, it just doesn't have the same optimism that I feel. I've never been to Kamikatsu, but these descriptions make it seem like they're rooted in tradition and community and people and even the future.

Kana:

I think that people have decided this is where I'm going to spend my life and with that decision is like, okay, well let's make this a better place to live in.

Leafbox:

Great. And the last question I was having was, you were talking about freedom, I think sekkotsu tsukuru 生活を作る, living, making your life.

Kana:

Oh yeah, yeah, yeah. Designing your own life.

Leafbox:

Yeah. Do you find yourself being more free now in this town? Or maybe you can elaborate on that freedom.

Kana:

Yeah, I think that in the countryside for me, I don't feel kind of tied into these kind of slots of time that I need to work in. I know I don't need to work nine to five and I have less conveniences available to me. And so if I wanted to cook, I have to decide, "Okay, do I want to cook from scratch? What do I want to cook with?"

And so I think it's just almost having kind of a blank canvas because I have so little to pull on, then I get to be more in control of how I actually and design your life comes from Nakamura-san, who really felt like he pulled elements of things. He got inspiration from his time abroad and from his past time in Japan and decided these are the things I want to bring into my life and these are the things I want to spend my time doing. And so I think because we have so little in the countryside, maybe not so little, but so many less conveniences available, you can bring that kind of mindfulness into creating a life that you want to live.

Leafbox:

Great. Kana, is there anything else you wanted to add today?

Kana:

No, I think that's all. But I didn't get to hear about you.

Leafbox:

Well, we can talk about me next time.

Kana:

Okay. Sounds good.

Leafbox:

Anyway, Kana, thank you so much. I really appreciate your time and it sounds like a beautiful place. Hopefully I can go to Japan one day-

Kana:

Yeah. Yeah, anytime. You're welcome.

Connect with Kana on her substack Tending Gardens or apply to be part of the inow program.