Interview: Ashutosh Joshi

Walking Across India: A Journey of Heart, Philosophy, and Connection

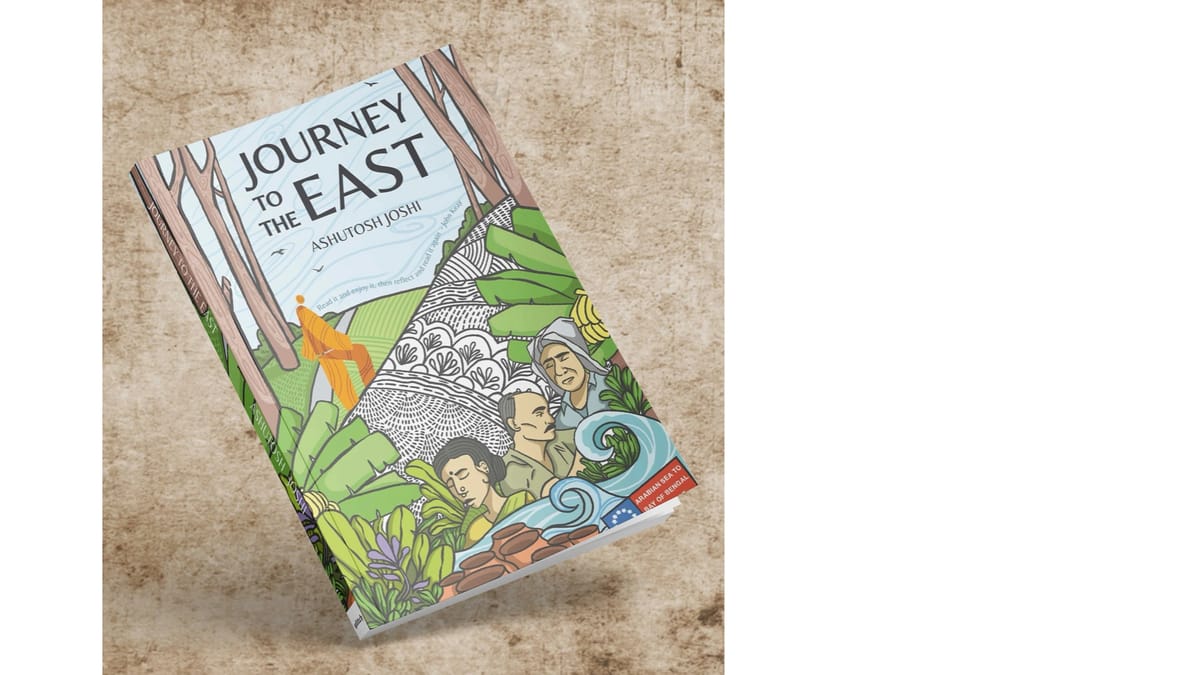

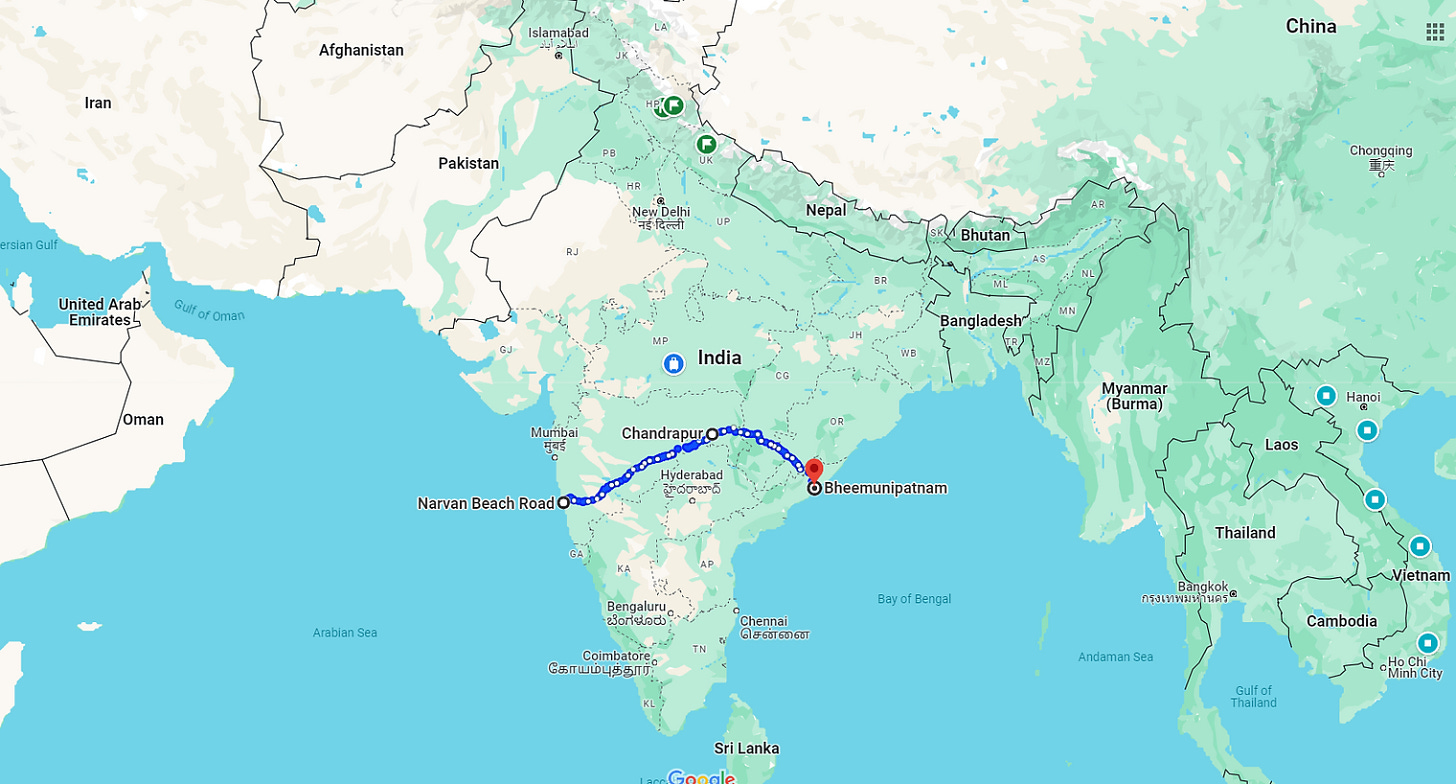

I had the pleasure of speaking with Ashutosh joshi, an Indian photographer and writer whose recent memoir “Journey to the East”, chronicles his 1800-kilometer walk through the heart of India, from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal.

Initially a project document the issues plaguing rural India, the project unfolded to become an unforgettable voyage of self-discovery. In this interview, Ashutosh reflects on human kindness, philosophical insights, religious perspectives, and societal issues he encountered during his travels. He talks about his background, the influence of Western philosophy, and his academic experiences in England and Scotland. Key themes include environmental degradation, farming crises, caste dynamics, and the impact of digitization on human connectivity. The dialogue also touches on the challenges faced by India under nationalistic pressures and the role of art, journalism and freedom of speech in highlighting these issues, his thoughts on spirituality and society. A story of universal human optimism and connection forged step by step, person to person.

Ashutosh's dialogue reveals both optimism for humanity's intrinsic kindness and concerns about societal trends driven by digitization technology and politics. His upcoming projects and thoughts on cross-cultural learning cap a conversation that is both a personal narrative and a broader cultural critique.

Ashutosh also writes The Book of Ptah, what Paul Kingsnorth calls “breaking the mould. Not just another Western semi-intellectual type talking about big concepts…[who] writes movingly about life in a very traditional Indian village, and how it is changing as the world does'“ - recommended.

This is a great honest story amidst a world of doom, confusion, polarization of a young man’s honest adventure and exploration of place, people and community.

Time Stamps

00:00 Introduction to Philosophical Insights

02:33 Life in India: Family and Background

05:51 Journey to the West: Education and Experiences

10:02 Cultural Observations and Reflections

15:42 Philosophical and Religious Explorations

16:03 The Concept of Kali Yuga

21:31 Western Philosophers and Psychedelic Influence

26:19 The Walking Journey Across India

34:08 Living Arrangements and Language Barriers

34:47 Caste and Social Dynamics in Rural India

37:08 Safety Concerns and Gender Differences

38:35 Media and Press Relations

40:12 Philosophical Reflections and Book Summary

41:47 Optimism and Human Kindness

45:15 Religious Polarization and India’s Diminishing Press Freedom

49:28 The Fallacy of Western Freedom and COVID-19 Reflections

54:11 Photography and Social Documentation

59:00 Migration and Cultural Diversity

01:02:14 Upcoming Projects and Final Thoughts

Links:

Ashutosh:

And I never really understood it until I actually went out to walk. This thing where you can jump into any place and anywhere and you will not be an alien. You will find people who are nice and kind. And, that's what I learned from all these philosophical interventions and all these religious and philosophical interventions that, at the end of the day, we are all one. And if we've. figure it out, how to connect with other people, how to make our, build our own story, then it won't be difficult for me to do this work. Yeah I think I just don't want to be a nihilist at the end of the day. So that's what I saw, and that's why I'm, optimistic, and I'm still being optimistic in the future as well, we are going through these tremors and trembles We are just trying to come out on the other side as a butterfly, it is a process, and we are in between.

Leafbox:

Good morning, Ashtosh. How are you doing this morning? Thank you for, joining me I just very appreciative of your time.

Ashutosh:

I'm good. Thanks for having me on.

Leafbox:

I just, about 10 minutes ago, I finished the last chapter of your book, and I was rereading parts of your blog so there's so much you wrote about that I had lots of questions. I'd like to just jump in

Ashutosh:

Yeah. No worries. I have some time today. so you're based in Hawaii, right? How's life over there? I've always thought about going to Hawaii someday.

Leafbox:

Oh, it's paradise. And since I saw in that you play ukulele, so I think you understand the history of the ukulele and Hawaiian music and Hawaii.

Ashutosh:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

So, you know, a different paradise. I think you wrote in one of your books that we're all connected. So, sending you a lot of metta from here in Honolulu.

Ashutosh:

Thanks man.

Leafbox:

Anyway, hopefully one day we can walk together here in Oahu or a different island, but the first thing congratulations on the release of your book.

Ashutosh:

Yes. Thank you

Leafbox:

How do you describe yourself to most people when you first meet them?

Ashutosh:

So I'm a photographer and a writer. I studied in India before and then I went on to study in England. [00:02:00] before that I took two years off, trying to hitchhike and trying to meet new people and, see whatever world I can.

That's what gave me the idea to actually go out further and go to a different country and learn more. in my core, I'm just a normal guy from a small village who likes to, stay in the village and, look around a bit and see the environment and see, how small we are in this entire thing. That's all.

Leafbox:

Ashutosh, why don't you tell us where you are in the world of India in Konkan, I believe, and, how long you've been there and maybe a little bit about your family. I'd love to know more about your family's history.

Ashutosh:

So I come from a place called Konkan. It's a small 500 kilometer stretch on the western coast. it's next to the Arabian Sea and my family is basically a small middle class [00:03:00] family, who has lived here for a long time.

it's a small village called Narvan from where we originate. My grandparents moved to a bigger city in search for job and opportunity, and that's how I came here. my hometown is called Chiplun. it's a very small city, town, whatever you call it. but by the Western standards, it's pretty big.

So yeah, that's where I live and when I'm in India, I usually dabble around between three different, places. One is my village, it's Narvan, Chiplun, which is my hometown, and then North Goa where I stay and, work and whenever I have to write or do any assignments, I go there because that's a much more kind of, Western style, where there's lots of people, writers, poets, all sorts of musicians. So you have a lot of, discussion and ideas about the world.

Leafbox:

And then could you just [00:04:00] give me a framework for how many people live in each of these three cities and then what your religious background is? Goa is so wonderfully diverse for people who don't know that maybe share some of that.

Ashutosh:

Yes. My village, it's about three, four thousand people. most of the people over there have, already migrated to Mumbai, bigger urban cities because there's not a lot of, work over there. Chiplun is much bigger. it will be, in lakhs, which is I don't know, million, maybe, in Indian it's called lakhs and it's three, three and a half lakh.

And then, it's mostly, Chiplun is mostly Hindus and Muslims. And then you have, North Goa, which is obviously diverse, but, people who live there come from all kinds of backgrounds, they are Christians, they are Muslims, they are Hindus, then you have a lot of, people who have been living there for a long time, maybe you can't call them hippies at this point because they are digital nomads now, And, there's [00:05:00] lots of people who have been living there.

My religious background, I would say I don't belong to any particular religious background because I like to take from every religion. But I grew up as, a Hindu Brahmin in, the kind of caste system in India you have, and you have the highest caste, which is Brahmin.

And I grew up in that caste. In my growing up years, I think it was a lot more orthodoxy, the scriptures say and what the religion says and all that. But my house was still a bit liberal with my grandparents being a bit more open about the entire process, which is how the actual religion is.

And that is why I don't pinpoint myself to Hinduism because it's a very fluid religion. It doesn't have a proper core to it, it is a philosophy more than a religion. So yeah.

Leafbox:

We can discuss the class structure. I want to know a little bit before we jump into your walk and your experience in your adventures, what brought you to the UK and Scotland. [00:06:00] And yeah, tell me about that experience of jumping to the West and what your experience and your observations were.

Ashutosh:

So I was traveling around India and Nepal for at least a year and a half where I met a lot of people from the West and I generally liked the kind of open mindedness that I saw in most of the people that I met.

So we were tagging along and traveling along, hitchhiking, all sorts of things and that made me think that the West in general is much more open. And it definitely has a lot more to do with art. So because my background was in arts, I decided that it was the right thing to do. I got into the University of Gloucestershire in England and I got a second year entry because I had, some courses done in India, which affiliated to that.

And after that, I stayed there for a couple more years and the entire process was. [00:07:00] More or less, trying to understand what I am doing, because art is always it keeps you questioning for more and more, and the more you read into it, and the more you, dabble into the surrounding areas of arts, which is, psychology and philosophy.

It makes you question more and more. And that brought me to a conclusion at one point that, also COVID happened during that time, and I was in, England at that moment. And when COVID hit, I stayed in, university halls for more than two weeks. two, two and a half months, which was a very kind of, soothing, enlightening experience in itself because there was no one around me for, those two months and the libraries were open.

So I went in and brought out all the, Western philosophers, Nietzsche Camus and, Sartre, everyone. Then I went into the religious [00:08:00] aspect of it. I tried to learn about many other religions, Christianity, to start with. one thing I realized that, at least in the Western philosophy, there was a lot of, nihilism and there was not a lot of what to do, if life is just like this, what to do.

And so I started looking into religion, which was more interesting, then came around to psychology and union psychology, which definitely helped me. And so I decided, rather than going back to India because of the lockdowns, I would do something a bit weird and go to Scotland. So I went to Scotland as a Work away, which is more or less like a site where you can join and then you can go to a random place, meet with the people, stay with them and work with them on the fields or whatever it is.

So I was doing a farm job for two, three months in Huntley, a small village in Scotland next to Aberdeenshire. [00:09:00] And that, shifted a lot of, things for me, as to what the Western culture is like. And it also helped me realize that, there is not a lot I can do about it, but there is definitely a lot of things that I can, change and help out in India.

And so that's what I decided that, I need to go back to India at some point. but I stayed in Scotland for a long while. I stayed in Edinburgh for some while. I was with a gallery assistant and, I sold my work. I did photography over there. I sold my work over there. And then came back to Cheltenham where I was studying.

Traveled around the UK. stayed for a year. did gallery assistant jobs in Bristol and then decided to leave.

Leafbox:

To interrupt you for a second, when you went to Scotland and you're doing the farm job, what did you realize about the West and Scotland? You said that you realized something, what did you realize then when you were [00:10:00] doing work at the farm?

Ashutosh:

I realized that, the Western society in general has become a lot more distanced from, the natural world. what I saw during those periods was everyone diving deep into their phones and their laptops and everyone was connected to the internet and there was no real sense of, bonding with nature at that point.

And, for some reason, I still feel like there is some of it left in India because, of the lack of, progress. And because of the lack of internet in many places, you don't have mobile networks in any places. So that's what I learned first of all. The second thing was there is a deep core of religion, in the West, which is slowly, sliding out and everyone is becoming much more atheist and, no one wants to have anything to look up to. And that is why they [00:11:00] have, it's everyone, but, that is why most of the people have started looking at science as a new religion. And that is why the university system that I was in, I did not really find any, importance in that entire system because, how do you say it?

There was no real sense of, questioning. There was no real sense of, bringing something new to the table. I was just told most of the times to Google something and bring a project out, which was not really what I went there to do. And if you were questioning the entire system, if you're questioning the society and the way it works and all of that is also one of the, philosophical questions that you have about life, right?

And that is somehow absent in most parts. The other thing was it's a very rigid society, at least in England, not in Scotland. Scotland was much more open and I can tell you that for 100 percent because it is much more connected to nature. the [00:12:00] free outdoors and you can just randomly walk into any place into the outdoors and, take a swim, whatever you want to do.

And then you come to England and you have a block on all of that. You cannot do that. You cannot walk through random places and all of that. And that maybe that is the reason why there's such a divide that I saw between this, between Scotland and England. but again, in Wales, I saw this, where, small towns in, in the places where there were coal mines.

they were much more connected with each other. As a community, they were connected. And maybe that has to do, it has to do something with being in nature. Yeah, that's the difference that I saw at that point, that the technological kind of, You know, leap into the future, but there is no grounding anywhere.

Leafbox:

So you don't think your kind of alienation was due to the fact that you're from another country

Ashutosh:

No, I don't think there was any alienation in [00:13:00] that sense because, at that point, I could, converse with most of the people Yes, they were interested.

Many people were interested in me, when I said that I'm Indian, it goes to, a category oh, he's an Indian, so he likes butter chicken, he knows what, to do and, the head nodding and all that sort of stuff, but then you start having a conversation when you start trying to, have a deeper talk about, how's life like and all that sort of stuff.

When you break the first couple of boundaries that everyone has in their head, then you start having a deeper connect and conversations. And I certainly had that with most of the people that I meant during that entire time. and so I don't think it was an alienation in that sense.

Also because everyone was alienated in that point. Me even having a connect with a lot of people during that time made it not seem like I was being alienated by the people.

Leafbox:

Have you read, Pico Ayer [00:14:00] or V. S. Naipaul?

Ashutosh:

No.

Leafbox:

Oh, Pico Ayer is a wonderful American, Indian, English cosmopolitan writer who is between places, he studied at Oxford, but he grew up in Canada and then he lives in Japan and he's a really wonderful travel writer, I just wonder if you consider yourself Indian or do you consider yourself like Pico Iyer being Post national, in a sense. You're post Indian, post British, Pico Ayer has this concept of elective identities, where people select aspects of their identity, and then you're an outsider, and you can always have this cultural lens.

Because in your book, I also feel that you're quite critical and neutral on India as well. Even though you're talking about the alienation in the West, I don't think you're soft on India. You're honest about its issues in the writing that I've read, it has its own problem.

In your writing, I see a lot of honesty in your critique of [00:15:00] daily life, poverty, corruption, all the issues that India as well also has. So I just wonder where you see yourself, you're still a young man, so maybe you haven't fully developed how you define yourself in that sense.

Ashutosh:

Yeah, I like that concept. I'll definitely check him out.

Leafbox:

He has this kind of global mindset. Some people are critical of it as well, but it's an interesting, he doesn't call it multicultural. It's more like a cosmopolitan view where you're, understanding place, like you went to Scotland, you're trying to understand the place you're critical of it.

You're also, praising its good qualities and whatnot, trying to be neutral or whatnot and selecting the best aspects of each place. Ashutosh, maybe we can jump, there's all kinds of things to talk about. One of the questions I had on your about page, you mentioned the Kali Yuga.

Enter this, framework and you pull from all kinds of philosophical traditions. tell me about the Kali Yuga, what it means to you, where we are in this epoch and How that's helping you [00:16:00] frame where we are and where things are going.

Ashutosh:

Kali, Yuga is a, is a concept in Indian mythology where, so the God takes avatars, okay. And. How I see it, it's more about evolution, like evolutionary theory, where we went from being from being this small particle which revolved around in the sea. Then we came out, then we became reptiles, and on and on and on.

The evolution goes, till you become, a human, a man, and then a responsible man at the end of the day. And so that's how I see the avatars in Indian mythology, where the God takes avatars. And so, starting from the very first avatar, it goes just like that, where you, you start with, tortoise, which is obviously, an amphibian who can live in water and then on the land as well.

And then until that, until when you become, the perfect, man, [00:17:00] and what it says is after all of this, When man become perfect, after it's the downfall.

It's the same story in the Bible that, we ate, man ate from the apple from the tree and then, the downfall starts. And that's the same story over here. But interestingly, it is the last avatar which is not yet arrived. And so they say that we are living in the Kali Yuga, which is the age of the Kali.

And Kali, is this God which will arrive at some point. It is similar to the story of, Christianity where, it's the forthcoming of God, right? And, I don't really think of it in a very religious sense, but I obviously see it in the way we are destroying, the environment around us, in a way we are suppressing all the other species to become the most powerful, the species that we were meant to be or something like that.[00:18:00]

In a way, it seems like ego and the entire scripture says that man will become more egotistic and more he will have a lot more narcissism in him, which I definitely see when I see people using the phones and, they're always looking down and all that sort of stuff. So that's what, Kali Yuga means in the entire perspective.

If you try to put it in modern language, if you try to put it in a religious sense, it becomes a bit murky because then you're waiting for someone to come back and, change everything for you. But in a way, I also see that the entire Indian philosophy is not about a god up there. It's about a God in you.

So you are, based in the image of God and, you are the one who is looking at the entire life. And then after many years that you have lived, you look back and then you realize that there was no one [00:19:00] else. There was just you. And so that's what I think. Kali means that you have to come back into your own body.

You have to regain your own consciousness from whatever it is scattered from the day you are born. Because, there is a society around you which makes you think in a certain way. Chains and molds you for 18 19 years of your life and then you're thrusted into a system which is not really helping people evolve in a better way.

They're not, it's not really helping people to be conscious about their decisions and their surroundings and all of that. So that's how I see the Kali Yuga.

Leafbox:

How does that contrast to, there's a lot of Western writers and you referenced them in terms of the machine and maybe you can contrast, the alienation, the disenchantment, and modernization and how does that play into the Kali Yuga?

I thought the Kali Yuga was like a period of the [00:20:00] fourth turning and of the end. So I'm just curious how it fits into your thinking of. your opposition to what you call the machine.

Ashutosh:

I definitely, think that it is the end, but there's an interesting, word in Greek mythology, which is the apocalypse that we use a lot in English as well.

when I researched more into what the word was about, I came to this Greek meaning of apocalypsis, which was not just the end of the world. Apocalypse means, ending and regenerating. It's the same, story in the Indian mythology, if you have heard of Shiva. Shiva is the destroyer, but Shiva also creates, he ends it and then there is another one who creates.

So It's that meaning of regeneration. It's not just ending of it. And in that sense, I completely, I'm on board with all the people who are calling it the age of the machine where everything is coming to an end. I do believe that there is a beginning that has already happened with a lot of people coming out of [00:21:00] these, systems and, living off grid lives, not, having their kids getting educated in the traditional sense of education.

people becoming more rooted. Both of these things are happening simultaneously. And I can say that because I've witnessed it while I was traveling. It's not just this one thing. I have hard time trying to explain these things because, it's never just one thing happening at one time.

It's a hundred things happening at one time and it's fast. Way too fast. And then, obviously, there is another theory which, Terence McKenna, he also lived in Hawaii, by the way, he points out that we are actually coming towards the end of time, and I have no idea when that will happen and how that will happen, but I presume that, I definitely have a lot more respect for, psychedelic scholars because they have written a lot of interesting things that normal people [00:22:00] will never even think about.

That is time coming to an end, but that time can be any time, right?

Leafbox:

Ashutosh, I'm just curious, how did you even learn about Terence McKenna? Is that because of Goa or just other hippies in Goa teaching you about, psychedelic philosophy?

Or how did, is that a common philosopher in India? Or what's your exposure? ,

Ashutosh:

No - Not at all a common philosopher in India. No one will know. Terence McKenna, Timothy Leary, no one will know, Ram Dass, Huxley, maybe because of his book, but, is not common in India. So I had a very interesting ride when I was in England and I saw a lot of people around me doing of, drugs, because obviously England is scarred with like everywhere you go, you see, some sort of drugs and it's readily available.

And I was a bit mature student when I went there. And I'd seen all those sorts of things when I was in India, when I was traveling around. And so I was never really like curious about it, but [00:23:00] I got curious when I was in Scotland. because I started reading about Alan Watts and through Alan Watts, I got an entry into the entire psychedelic field.

And then I came across, Terence McKenna, Timothy Leary, I started learning more about psychedelics. I started getting into the research of it, the literature and all of that. And it came to a point where I was questioning my own religion and I was questioning my own identity, right?

Like growing up, I grew up in this religion, which says this is obsolete, like there is nothing above God and all that sort of stuff. But then I started, when I started reading, my religious books, I learned that it's nothing about that. It was completely a different story. And, what happened, back then has no hold on to the modern times.

And people are just, not actually reading what is written. And then most of the stuff that I was reading made no sense because it was way too [00:24:00] poetic and I always thought that this is not written in a normal state. It has to be in a different state of mind, consciousness, whatever you want to call it.

And I obviously had, my experiences with the most normal, drugs, which is weed. but I never had any experience with psychedelics. So I started first reading and researching about it. I got, hold of Terence McKenna, then Dennis McKenna, and the entire psychedelic field. And I started learning more and more about all this.

it dawned upon me that there is this small part in Western history that is being forgotten completely the 60s 70s 80s when all these things happened and Terrence's ideas were really mind blowing. I don't think that all of the things that he said will come true because he also said 2012 will be the end of the world which never really happened.

But yeah, like there is a definite shift in time, which will happen around [00:25:00] 2000. 10 to 12, which was the coming of the phones and social media and all that sort of stuff. So it's the perspective, how you look at it, but yeah, Terence, Timothy Leary, the kind of ideas he has put forth, Ram Dass, although he went more into religious side of it, all these ideas definitely kept a hold on me when I was in Scotland.

And then I continued that search in England. Then when I came back to India, I kept that search on going to Himalayas, traveling all around that place, searching for all these, small tiny spots where there were, long lost hippies living there and then coming to Goa finally and meeting again all these people.

And my way of it is I try to bring their, past back because a lot of these people have changed now, owing to the modern times and all. So I sat with, a lot of these long time hippies and I asked them about, life and how you lived when you were in [00:26:00] 60s, whatever it was. And I learned a lot more things about how the world was like, as to the transition of where we are today, where, too connected and too anxious and depressed and all that sort of stuff, which was, not so common back then.

Leafbox:

So let's jump into your book. your journey into these philosophical realms takes you back to India. And what motivates you to walk from the Western side of India, all the cross to the Eastern side. Tell me about that, where that comes from.

Is that from your curiosity to meet people and how has that experience.

Ashutosh:

Yes, so it was definitely about, experiencing, a dying culture. That's how I saw it when that walk started. There were many reasons for it, because at that time, where I live, we had, floods. And that's where the thought came from. But yeah, this was a long, process. And I had this thought [00:27:00] even when I was in England that I want to walk India and it was more so about, experiencing the culture, experiencing something that, you have never experienced even while living in India. and obviously there was

This thing where you can jump into any place and anywhere and you will not be an alien.

You will find people who are nice and kind. And, that's what I learned from all these philosophical interventions and all these religious and philosophical interventions that, at the end of the day, we are all one. And if we've. figure it out, how to connect with other people, how to make our, build our own story, then it won't be difficult for me to do this work.

So that's where all this ideas came from. And then obviously, Because I come from a, photography, journalistic kind of background. I also wanted to make a project while I was going, and that was the farming crisis, what was happening in India. There's lots and lots of suicides [00:28:00] happening in the central part of India.

Because of a lot of, lack of governmental, infrastructure. there is a lot of corruption and all sorts of things. And then. when I actually started walking, I realized there's many problems and it can't be pointed out to one thing. there are many issues, many different ways of looking at it.

But yeah, it has to do something with people becoming distanced from reality. and by reality, what is in front of you, what is around you at the time, in this moment. What I saw when I was working was people were there in that place, but they were not at all connected to the place around them, which was obviously a different case 10, 15, 20 years back.

So I've written in my book that I knew that I was walking in a place which used to be a colossal elephant at one point and now I'm just witnessing the tail of that elephant. So that's [00:29:00] what it was.

Leafbox: So how did you choose your route? Because India has such a long history of sadhus and pilgrimages and religious walkings and I'm just curious how you actually chose your route because you seem to have Yeah, tell me about that.

How did you choose the route you were going to walk and how did that go?

Ashutosh:

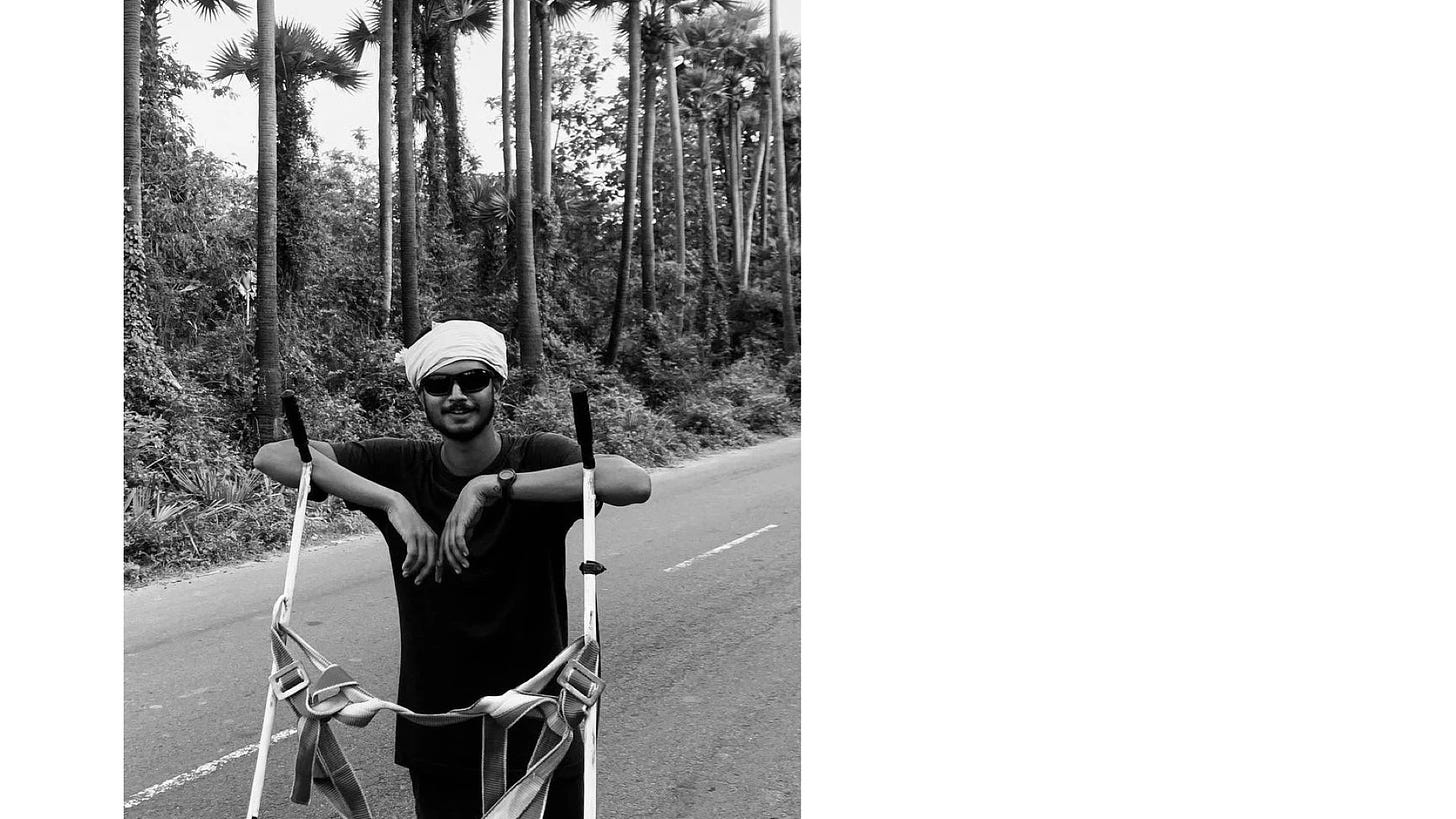

Yeah. so when I started it off, I knew for sure that, I would need something to go along with me because I cannot walk with a hiking bag, because it will be too heavy.

I met with a friend of my dad and he manufactures Heavy industrial equipment. And, I gave him a rough sketch of what I wanted and he was really enthusiastic and, he and all the workers in his factory, manufactured that trolley within three days.

And it was perfect because it, took all of my, belongings on it, like my backpack, my tent. a carpet mat, whatever I slept on and [00:30:00] everything that I needed was in that trolley then. And while figuring the route out, I just knew that I need to go to the next side of India. if I had no responsibilities whatsoever, I would have thought that I'll keep this work indefinite.

And I still do think that I'll do that someday, but I needed like a closing point, so that I had a clear goal in my mind And so I first decided a route, which was along the Central part of India, which went up from Nagpur, through a couple other, states, there's a long wadi that happens in Pandharpur, which is, a religious destination it's similar to Camino de Santiago, where people go out for walking long distances, to reach a temple, just like a church in Santiago.

And so I wanted to, [00:31:00] incorporate that temple in my walk because I'd heard a lot about Wari, so I kept that in my route and just like that I had, pointers, very random pointers where I had heard about stories of suicides and, dry climate and lack of rain and all that sort of stuff. And going all the way through to a place where I met a guy who I was very impressed with.

He runs a hospital in the middle of a jungle where it is guerrilla insurgent jungle where there is not gorilla warfare in jungle where, the people from that jungle are actually fighting with the Indian, state, to preserve the land, to preserve their ancient, jungles. And this man lives in the middle of that conflict and, I was well impressed by him and I wanted to meet him along the way.

So I went to that place. And then he gave me the idea to go through the forest, [00:32:00] which I was obviously stopped by police, interrogated, in a police station. I was asked, A lot of times to not go into that place, but at the end of the day, it was my decision. And so whatever happened, happened.

so I went in because he said that if you don't have an iota of fear in your mind, then you can cross it very easily. It's not that difficult. it's just that everyone is, afraid of even walking into that place. So to that point, I'd already walked like half of the walk, and I knew that every person, if I was nice to them, they were nice to me.

And even when I saw any problems happening, it was usually because I had fear in me. it was not because the other person gave me that. It was me who had that fear. So that's how I went through that, area and then, the rest of the walk. Yeah.

Leafbox:

So [00:33:00] Ashraf, how many, kilometers were you walking a day on average?

Ashutosh:

So it was one time I had to walk like 43, 44 kilometers in a day. most days I was walking 25, 30, 35 in that range kind of kilometers. I would wake up early at 5. 30 and start walking and then 11. 30 I would stop and find a tree or a shade where I could just rest for a bit.

if I had people, I'd speak with them throughout the afternoon and then around three o'clock, I'll start walking again when the, sun comes down, because obviously it's like 45, 48 degrees in some parts, Celsius,

Leafbox:

What was your split? In your book, you often stay at people's homes, but how many nights were you, on average, just half the trip wild camping, half the trip staying at people?

Ashutosh:

Yeah, so it would be more of 60 percent sleeping in other people's houses and temples. or gurudwaras. One time I even was invited by a Muslim family to sleep in their house. The 20 [00:34:00] percent would be government rest houses because when the Britishers were in India, they built a lot of rest houses along all this area.

There were government rest houses and forest rest houses where I would stay for 20 percent and then 10, 15 percent would be actually putting up a tent and living in the tent. But I got to live, in other people's houses, and everyone was very welcoming.

Maybe it also has to do. with me knowing, the language, maybe it's Marathi in Maharashtra. Hindi, is still possible in Chhattisgarh and Orissa. And then in Andhra Pradesh, obviously I could not speak, the language over there, but still, I got along with a little bit of English wherever I could, but I wasn't there for a long time.

Yeah.

Leafbox:

And then I'm curious, going back to your state as a Brahmin, how important, I was just having lunch with someone today, and I was telling them that they have to go to India once in their life, [00:35:00] and it's just so radically different for Westerners to even comprehend the reality of daily life in India.

How important, was it a challenge for you being a Brahmin? people ask that, what's your daily, I don't know what 2024 caste culture is like in rural India. How important is it? How unimportant is it? What's the reality of that?

Ashutosh:

Yeah, so in more so there were some urban hotspots in this walk.

And wherever there were these urban hotspots there, I found like no real kind of cast class kind of divide. I think it was a divide more on a religious basis in these urban centers, obviously because a lot of hatred, on phones and news and everywhere. But, in rural areas, I won't be the right person to say any of this because I come from a Brahmin family.

And even if I consider myself as not belonging to any religion, [00:36:00] people, can obviously identify me right away when I tell them my surname, my last name, because it is a Brahmin surname. And so in some places, in temples, I was obviously allowed very easily. People would entertain me and all that sort of stuff.

But most of the time it was because I was very receptive and because I was very, attentive to what they were saying. In some places, obviously people directly asked me what's your name, what's your surname, what caste you belong to and all that sort of stuff. but this was very minimal. It wasn't in many places and most of the times, yeah, it was an easy ride.

Again, I think it will be very difficult for, an outsider or a, religious minority to travel something like this. But I've seen people who do this sort of thing on bikes, who come from different castes and they do this on bikes. So I'm, yeah, I don't know [00:37:00] like how this would be like, but obviously it will be, and it has been a much more easier ride for me.

Definitely. I won't lie.

Leafbox:

Do you think, were you, in a lot of the book, you're concerned about, serpents and snakes, but there's a lot of. I find India quite safe, but if you're a woman, for instance, it's very dangerous. Did you ever have concerns about violence or being robbed or what was your reality in that sense?

Ashutosh:

I never had that concern, throughout the entire trip. It also has to do with me being really open to anything. And when people had in parts, wherever I was going through these, small bits and pieces where people had guns in their hand and, it's normal in, America to have guns, but in India, it's very random, that people will have guns.

Me being very normal with even that made it interesting for people to even have a chat with me and I would straight [00:38:00] up go into what's your life like where are you from and what you do blah blah blah and I start speaking with them right away and so it became much more normal and But yes, it will be a bit different if there was a woman going on a walk like this.

But again, there are exceptions. Like I've seen, I've met women throughout this walk who have done similar things. Not walks, obviously, but on bike. Walking might be a bit difficult, I would say.

Leafbox:

Could you tell me about, you started to get a press following and how that relationship was.

What was that relationship like and was that surprising to you and how did that develop?

Ashutosh:

Yeah. So there are normally, left leaning and right leaning newspapers in India. And, like everywhere else, but more so right leaning at this point. And whenever, I gave a [00:39:00] press release, wherever I went in a city, if someone invited me, I told them the reality of India, what I saw, how crazy it is, how propaganda is stemming to the core of everywhere.

And how the environmental degradation, the farming crisis, everything that was real and what was in front of me, I told them. I even told them how, oppressed I saw, the press people. And the kind of people who really wanted to tell the truth, were never allowed to tell the truth.

And then the ones who, got off by telling lies were the ones who had the bigger cars in, who came to interview me. So all these things that I said, none of it found like coverage in the media. All they wanted was a guy is walking from the West coast to the East coast, talking about environment.

And, maybe it has something to do with this greenifying of everything. Everything is about climate change at this point. I think everyone wanted me as a [00:40:00] character that was riding on this wave of climate change and protest and all that activism and all that sort of stuff when my work really wasn't about it at all.

So yeah, that's what I saw.

Leafbox:

So what is your, just to summarize for people who haven't, are going to read your book, what is your walk about? Just meeting Indian daily life or what did you conclude at the end of your walk or what was your intention? What did you conclude at the end?

Ashutosh:

Yeah, so the intention when I started this work was more about, documenting farming crisis and learning more about it.

And I never intended to write a book about this. but then when I started the work, all these, philosophical questions that I had started popping up again and again. And then I decided to go with the flow. Whatever destined to be will be. And so I started moving randomly with the flow, meeting people, learning about them, learning about their lives

In a way, it was also a [00:41:00] very, internal kind of, walk where I started, figuring out some things about myself, about, my situations, about the surroundings that I was in. And at the same time, the human condition, what we are made of and what we are about and how we are lost in this entire space.

And yeah, that's what the book is about. social commentary, daily lives, and obviously philosophical ponderings all combined into one.

Leafbox:

And then, one of my favorite chapters the last chapter is when you go to the temple near the end and, she offers you the idli, and you just see how wonderfully kind people can be, and I think that contrasts with some of your chapters, which are a little bit more harrowing, the flooding and the schizophrenic Episodes, and so it's an interesting contrast.

I'm just curious, you end with a very optimistic note on humanity. Maybe you can expand on that and how you contrast that maybe with some of the alienation or some of the [00:42:00] degradation of the spiritual basis that you find in the modern.

Ashutosh:

Yeah I think I just don't want to be a nihilist at the end of the day.

And I can tell you that most of the work, like 90 percent of the work was more than kind because people were just They were amazing. They were very receptive and kind towards me. They got me food, sometimes even two tiffin boxes, at one night. Just bringing the entire village wanted to give me food, whatever they had.

Everyone wanted me to eat. even in places where people don't have anything to eat, they were giving me off like whatever leftover they had. This is the kind of optimism that I saw, the hope that I saw, That yes, you would be whatever the world would be up and down, people would be owning yachts and, big houses and penthouses and buildings, whatever.

And then people would [00:43:00] obviously be living in absolute poverty. And yet, everywhere, there is some sort of, human condition, I think, to be kind at the end of the day. if we don't project any of that, and we just be normal, we just be human with them, they don't want to be talking about all these things.

They don't want to be talking about these, superficial things because what they're living right now is in front of them, most of them were farmers. So their life was literally in front of them. It was their farms. So that's what I saw. And yes there is. obviously a very spiritual core to India.

I read Ramindranath Tagore, some while back when he went to Japan and came back. This is in 50s and 60s when he went to Japan and came back and then, even maybe before that, but he wrote about, India never losing that spiritual core. and he said it is because the way people live, it's in the living.

And I never really [00:44:00] understood it until I actually went out to walk.

And I saw most of the villages where, there's five different communities living with each other, sharing each other's culture, and living harmoniously at the same time. this is very, rewarding, I think being in India and being an Indian and seeing this, firsthand, as opposed to what we are made to believe at this point that, there's a great divide in India and everything is different and, everyone is different, and we need to be focusing on our own religion, and we need to be singular.

We cannot be pluralistic thinking. but then it's the Indian spiritual core, where you have pluralism in the entire, people.

So that's what I saw, and that's why I'm, optimistic, and I'm still being optimistic in the future as well, I think this is, it's called, when the butterfly, is coming out of its chrysalis, I think that we are going through those, as a humanity, as a human [00:45:00] species, I think we are going through these trembles, because of these extreme digitization, that we are going through these, tremors and trembles

We are just trying to come out on the other side as a butterfly, I think. it is a process, and we are in between.

Leafbox:

I'm curious just to go on the darker side of India for a second. you talked about the journalists ignoring your critiques of Indian society, of the, nationalistic Hindu, government, is their freedom of speech in India?

What is the reality of, I know they banned Tik TOK. what is the reality? Is the government trying to augment the inter religious tension, social media. Tell me about what's happening in the average mind of let's move away from the farm, but to the urban person, are they driving consumerism?

How's the internet affecting them? How's propaganda driving? I just want to know what the reality is like.

Ashutosh:

Yeah. So it's definitely a [00:46:00] religious polarization at this point. they are trying to move, different religions away from each other. and minorities are being suppressed, that's for sure.

you can see it in newspapers, you can see it in television, anywhere. But, it's hard to say that there is no, press freedom in India because obviously there's a lot of people who are, doing that on YouTube and all these other mediums. So it's still a bit freer, not completely let's say Russia or China, where everything is monitored.

it's not gone to that state. It will take a long time to reach that state, but obviously if they have that, power with them, then they'll definitely try to make it more like a Chinese society where, they have, a complete hold over the society and they dictate what to think and how to think and, everything that they do, is dictated upon by the government.

by the big brother of the state. but yeah, when it comes to, press, lots of people are [00:47:00] in jail at this point. Lots of poets are in jail. Writers are in jail, just for speaking out, their mind and just for having differing, in opinion from what the state knows. And this has been going on for some time.

It's not a new thing. what I'm scared of is that, the kind of progress that India has made as a nation in the last 70, 75 odd years, coming out of that rigid caste system and, being much more, linear and plural in that sense, These people don't want that. They will definitely be wanting to, push away from that, going back to the original caste system and having hierarchical system.

and you see it in the entire agenda, how they, act and react on specific things. I won't say that, I'm not allowed to say anything. I still do. But, I do it in a sense where if I say something, I have 10, 15 people around me from my [00:48:00] city telling me that, like literally sending me hate mail saying that, you are anti Hindu, your anti India, you are anti this and that or the other,

This is how it is. And if you speak out, then someone will send you a message saying, there was this lawyer who used to speak out a lot and then, some, random politician, just, put him down. This intimidates you, right? These are not the kind of messages that you want to read when you're being critical, of your country.

and I am the least critical guy because I also talk a lot of good about India, but no one sees that good. Then, when I say something about, Muslims, for example, I'm directly thrown into a caste where I'm Muslim pleasing, but then I say a lot about, Hinduism as well, which no one wants to listen to because, because people are not reading what they are, living or what religion they are, whatever religion they have.

So there, I think it has come down to. Pray to this one God that we tell you [00:49:00] and the state will look after everything else. And, we need to have a Hindu majority state because there's a lot of Muslim majority states and there's a lot of Christian majority states. So we need to have that in our constitution at some point.

That's what they're going to do. And that's how the situation is and it's, it's very grim at this point, but let's see. I wouldn't say it's completely bad.

Leafbox:

What do you think Westerners or people outside of India can learn from this? You were in India, during the COVID, lockdown, and you seem quite critical of that experience.

Do you see parallels there? Or where do you think the West, do you think it's still more free or less free or what can we learn from? So what can we learn or not learn or what do you, what can we take from your thoughts?

Ashutosh:

I definitely think that, the West is not free. Like they tell you that the West is free. yes, obviously, there's a lot of, freedom in democracy, [00:50:00] left. it can be twisted and changed, but even in America, you have a very rigid two party system, which is hard to break through if someone else wants to break through, right?

similar in England. where it is even more, polarized, at this point. obviously Brexit was, one such example. when I was living there, it happened when I was living there. so yeah, people individually can become free. it's very hard for a society as a whole to become free because, you're putting it out on someone else, a random guy, who will help you out, a president, a prime minister, a figure, whoever it is, it can't happen, you have to figure it out for yourself, and that's what, all these religious scriptures, that's what Jesus said, that's what, Krishna said, that's what, Lao Tzu said, it's within you, you have to figure it out on yourself, but Western society as a whole thinking of how the digital landscape was used during COVID, it's horrible, because I'll tell you a story, right?

[00:51:00] I was, living with a friend who had downloaded this app that you had to, during the COVID time. He was in Oxford in a small party. It was not even lockdown and it was a small party of some 15 people, 20 people. And because one of the guy had a notification on their phone that they were, tested, positive for COVID, suddenly when he came back to Cheltenham, he had, a notification on his phone that you have to isolate and you have to do this, and this.

And that was strange enough, but when he went to his house to his roommate, she literally distanced him and she was like, you cannot come back with something like this. it's making people polarized. It's making people, push away from each other. And it's so strange that it is just a random phone in their hand, which was there.

He never got COVID, nothing happened to him, but it was just a random phone in his hand was connected [00:52:00] to the internet and was in a limited distance to the other phone, which had this notification, and he immediately had to isolate. Not just that, even the, BBC, even the government, the way it was using this entire thing to instill more fear within, the people, it was appalling.

And, if you try to speak against it, you're just anti science, and it's not At all that, like I, I am definitely for vaccines, but I'm not for vaccines if it's not done rightly, that's what I said. And because even in India, it was horrible because we, when I came back from England, it was my brother's wedding during the lockdown.

And, I was, the entire step I was asked for, bribes all around India, wherever I went. And I traveled a lot. I didn't care about whatever. I just traveled, because I knew that if I traveled, hitchhiking or in a bus, no one really cared. It was only if I was traveling, in an airport [00:53:00] that they actually checked the certificates and all that sort of stuff and isolation.

And it was all about money in India. even doctors who I know very well, good friends of mine, all of them said that we, we can't do anything because it's the entire structure, which is, which is, like that.

Leafbox:

That was one of your essays. I enjoyed that essay about the corruption that, the guy wanted, 20, 000 rupees.

And then he dropped it to 10, 000. I forget how much. And then I don't think you paid him the Bakshish. But the only good thing about the chaos of India is that sometimes the rules are just, they're on paper, but the reality is nothing there. Yeah, so you just have to laugh. It becomes the good thing coming from India.

And if you're from a third world, a developing country, I grew up in a developing country as well. You just see through some of the governmental propaganda sometimes. It's just theater, right? So in India has so much theater. There [00:54:00] is unbelievable theater everywhere all day long. So that, that's a good thing that you still keep.

I guess you have to keep light and humorous, right? I mean, yeah, everything's dark. So what one thing I would love to end on is tell me about your photography and some of the projects you've done, how you select your, subjects and what you're trying to do with photography as well.

Ashutosh:

Yeah, so my photography is mainly about portraiture and social documentation.

So I dabbled into journalism and photography at the same time. recently, I was working on a project that had to do with environmental disasters in the state of Gujarat, where the prime minister comes from. My other projects are in a similar line where I see a migration of people who have come to urban areas or nationalities who have shifted from one place to another.

And I try to incorporate that migration with [00:55:00] journalistic side and portrait in my photography. My photography is, I've had a couple of, exhibitions in India, some in, England and, my photographs are in galleries or private collections in Scotland, England, Europe in some parts.

I sell, them, in a limited edition kind of scenario. So that's what I do,

Leafbox:

When you select your topic, do you have the same approach you did to your writing and to your walking project? What's your interaction as a photographer between the subject and what's your thoughts on that?

Do you approach it the same? You seem very direct. You just jump in and where do you, are you more aloof?

Ashutosh:

No it's the same thing. Like recently I went, when I went to this project in Gujarat, which is like two, three weeks back, I had to make connections right away. Otherwise I could have not got what I wanted from that project.

And a lot of it is confidential, so I can't really say a lot of it, but, so this, [00:56:00] approach that I had in my work, where I directly go into speaking with the other person, be a total extrovert, and try to speak with him about his family, about his life. And what it makes is it brings them down from the clouds directly onto the ground.

And then you can have a normal conversation as if you're just, a friend, who is meeting after a long time. And that is a very easy way to then, take pictures and take videos or interviews, whatever it needs to be. so I incorporate that side where I say that we are all one. I actually think that when I'm going there and then I bring it down to my, journalistic side where I have to actually ask them questions because otherwise I'll be talking about random stuff, right?

Like I will never come to the topic that I want to discuss with them. So then I bring it back to journalism I'll be much more direct and I ask them questions that I have on my mind. When I'm taking pictures, [00:57:00] most of the times I don't, ask them to pose or anything.

I just keep talking to them and I lift my camera and take pictures right away. Sometimes it's to tell them like, I'm going to take a picture. So people get too, I don't know, claustrophobic or something when I tell them that I'm taking a picture. in a lot of Indian, rural areas, people don't allow you to take their pictures because, there has been like a lot of people in the past who have come there, taken pictures and sold it somewhere else and, used it for all different kinds of things.

Even the government uses like random people who are working as laborers, they take pictures of them and showcase them as people who are getting benefits from their schemes or something like that. So they're very, scared of giving, out their identities to other people. And it's, I don't know if it's the same thing, but somewhere in Africa, they had, this, feeling that, when you take a picture, you're being captured by the devil or something like that.

But I still think that there is that sort of, feeling in [00:58:00] a lot of people in rural India that, you don't have to give your image out to someone. So yeah, this is the most organic, natural way to get into it because people obviously take each other's pictures, right? It's not that they are not taking pictures anytime, but it's just that they don't want to give it away to other people.

So that's how I go about it. And the topics that I choose are mostly around, gender disparity in India, then migration, environmental disasters. and that's what I normally take pictures on.

Leafbox:

Yeah, shooting environmental, pollution in India is very dangerous.

Just the companies can be quite, and I forget the huge chemical disaster in this 80s. I think a lot of yeah. Bhopal and it's just a very corrupt country. So it's very dangerous. I've been blessed to have been to India and, it's a very difficult place to be, but very inspiring and very lively and it's just such a counter to the [00:59:00] West.

since you cover migration so much, and I guess you were a visitor in the UK. What do you think of the migration? In England, for instance, you have any thoughts or, there's a lot of migration in the UK and Europe. And just if you have any thoughts and there's a reverse migration.

So if you thoughts on that.

Ashutosh:

So I think it is like, The past, five, six hundred years of problems that have been created, that are just coming back to haunt, the Western society. if I want to be, totally blunt about all of this, it's that, And, The approach to it, I still think was right until now, and it's still right in some parts.

I see that, a lot of migration can definitely be a huge issue, but then Nothing is being done on ground where they live to actually better their situations. Because obviously there's a lot of money [01:00:00] in the West, which is just lying around and, not being, used to a right place. And if we, End up saying that we are all one and God has all made us in the same image and whatnot, then we obviously have to be, kind towards the people who are, fleeing away from all these, disasters that we are creating and everyone is to blame, right?

Every single government is to blame for this because I see that normal people are much more nice. In Cheltenham we had a lot of migration from Eastern Europe and people were so nice to each other. it's so strange that governments take stand which are horrifyingly anti everything.

people on the most parts are so normal you need labor, how can you progress a country if there's no people who are going to do all the jobs that you need? Because definitely I saw this in West that no one wanted to do these jobs. And that is why you had a lot of, [01:01:00] Indian Pakistani Bangladeshi migration in the UK, who, you step into Heathrow and everyone around you is brown.

It's strange, try doing away with all of them and the British society cannot function. So you obviously need a bit of migration because it encourages diversity, then it brings different cultures, it brings different ideas to the table. but then obviously there's also the other side of it where it also creates a lot more separation when it becomes too much.

so I don't know where I stand with it, to be honest.

Leafbox:

Yeah, no, it's a huge, I'm just thinking coming from India, there's just so much internal migration. a Gujarati and a Bengali are totally different planets, right? So I don't think people in the West. If you haven't been to india, it's hard to understand just there's a billion people there.

Ashutosh:

Yes

Leafbox:

It's just really

Ashutosh:

In the street that I live on right now, and this is not even a big city there is at least 60 [01:02:00] to 70 different cultures living in this one single street. this is also within India.

And there's 60, 70, 80 different cultures living in this one single street, which just spans about 200 meters, which is crazy,

Leafbox:

What other projects are you working on? tell us about your book launch. What else are you doing?

How can people connect with you?

Ashutosh:

Right now, the book about this entire walk is definitely out now, you can buy it from my website for now, still figuring it out how to put it on Amazon and all of that, but my website is still available. it's www.ashutoshjoshi.in. you'd have to type it out at some point because it's a very hard name to pronounce, and yeah, the next project that I'll be doing, is after, the monsoon, I'll be, going on another walk through the, Western shoreline.

I've been writing about this on my sub stack, the book of Pata and, I'll be walking this 500 kilometer stretch on the Western shore, which is where I live [01:03:00] because, a lot of damage has already been done over here, and it will continue to be done if there is no general awareness or, an uplifting of, general conscience about these issues, the government wants this entire stretch of land to be developed in the, most, horrified sense of development where they want to bring in chemical factories and ports and, all sorts of factories which are going to harm the environment and the nature around this place.

And I was never going to do this, but it's so close to heart because I actually live in this place. And then this development also cuts, through a road through my village where they are going to destroy a hundreds of years old, forest, which is the last remaining strips of forest in India.

and so I'll be walking this, people can obviously help me out with that, by reading more of my sub stack, that I write about this. And, if they want to [01:04:00] donate for it, then I'm all up for it because, living in India, it's not so good for, artists to actually live here and make their own workout because people are not really interested in art in India, because we have a lot of politics going around.

So yeah, people can do that, buy my book and support me in whatever way, they find possible.

Leafbox:

And then one of my last questions is, the title of your sub stock, the book of path. That's from the, yeah. Give me the reference to that. That's a Egyptian reference.

Yes, that's an Egyptian.

Ashutosh:

Yes. It's the Egyptian god who writes, so he's a writer god, and because a lot of Egyptian mythology. It's trickled down into the Greek culture and all of that, and I was always interested in, Greek mythology.

This entire character seemed like a very interesting character for me. so he, wrote a book, and it's called the Book of Ptah. So I was like, no one is going to use this. No one is going to go [01:05:00] back in Egyptian mythology to bring this random character. So it might be interesting to bring him back who is a writer god and he writes about, everything that is happening in a society.

So that's me.

Leafbox:

Great. is there anything else you'd like to share? Anything else you'd like to share for people, especially in the West or? What we can take from your thoughts and India.

Ashutosh:

I think, there's been a dip in tourism in India.

Definitely. I've seen it in the last couple of years because before COVID and after COVID are completely two separate realities in India. I'd like more people to who are interested in India to actually come and travels like this. I would like someday down the line to actually host, a sort of a long walk or a hike, through the very rural Indian villages, which I'm pretty sure will stay the same for the next 20, 30 years, at least.

If people are interested in something like that, please do connect with me. And I'd like to encourage people [01:06:00] to come to India and see all of this. Also encourage me because that also keeps me going. Because here, I find the lack of motivation around me, in this place.

all the motivation that I get is mostly from UK because I lived there and I have a lot of connections from there, but also from the Western, society, and the people who are still reading long format and who are not, as connected to internet as they used to be, they are the kind of people who I.

I like to speak to so yeah, please connect and thank you. this is like really interesting. I was not expecting it to be such an interesting, discussion. So thank you for having me on that.

Leafbox:

Oh no. I just like to find interesting people. So maybe one day in India again.

Ashutosh:

Yes. Perfect.