Interview: Aaron Moulton

Aaron Moulton is an American curator based out of Denmark. Formerly with Gagosian Galleries, and other international galleries he is interested in secrets of creativity, the evolution of art, perception, and roots his curatorial practice in anthropology, journalism, innovation, folklore etc.

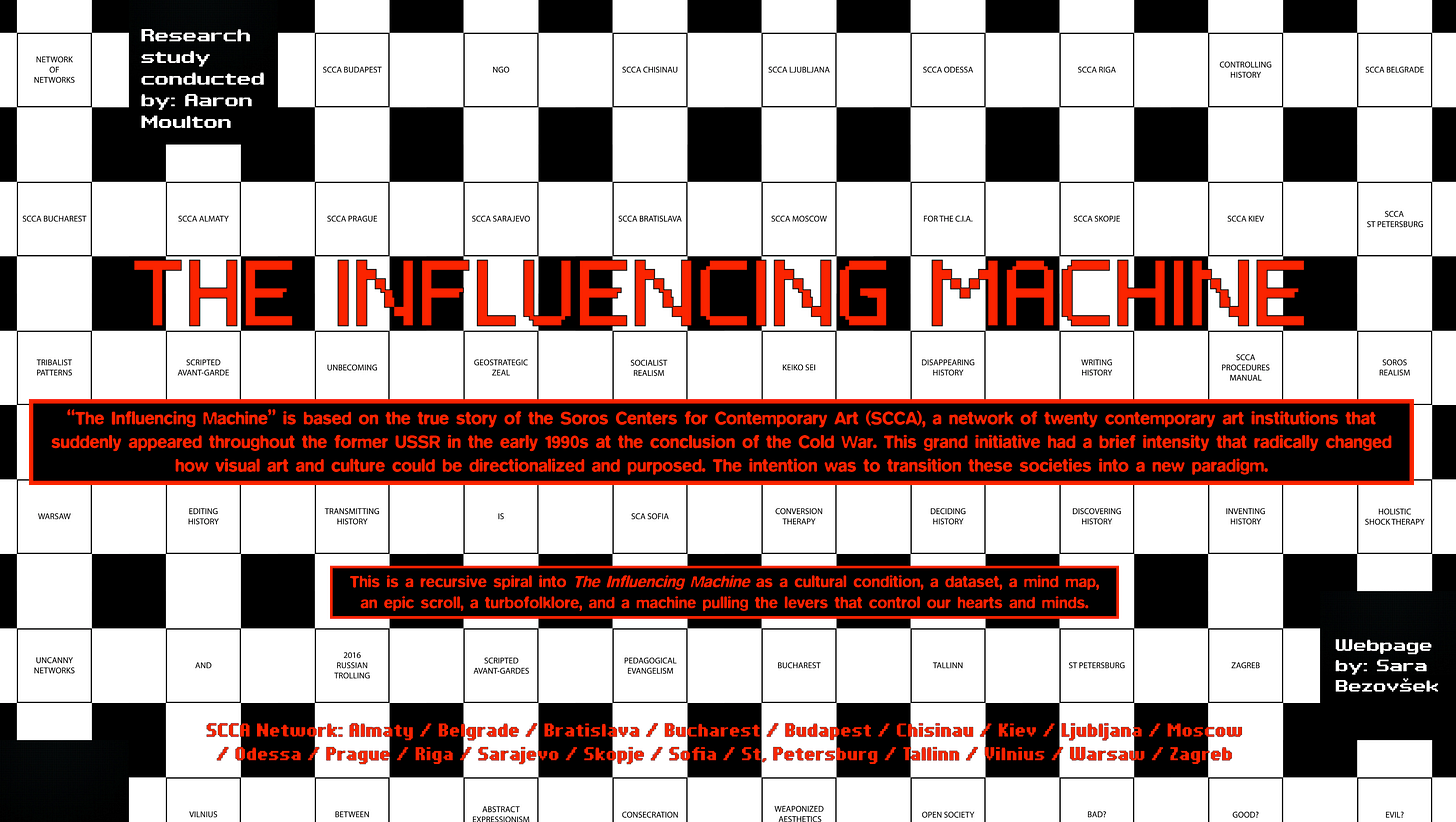

I first became interested in Aaron’s work finding his massive, fascinating and riddle like exposure of the Soros Centers for Contemporary Art. We discussed this project but also survey some major curations over about 20 years to understand the arc of his exploration.

Major Works / Projects Discussed

- The Influence Machine (PDF)

- Each Memory Recalled Must Do Some Violence To Its Origins @ Undisclosed Location Utah 2012

- AMERICANAESOTERICA

- Trito Ursitori

- Homage to Hollis Benton

- Homage Benton Interview

- Seeing Eye Awareness

Connect with Aaron Moulton

Photos / Videos / Images Courtesy of Aaron Moulton

Leafbox:

Aaron, well, first thing, thank you so much for participating in this. I was really fascinated by your work. I have some artist friends who do similar, I'm not going to say similar, but they do large installations, and they all kind of started with a similar history of building haunted houses as children. And I saw that in one of your works with the haunted house in Utah, and then I saw some of your work on the Soros Foundation, and it's just, it all fell into some of the topics I'm interested from psychological operations, art, mimetics, anthropology. I found like, wow, what a great artist, and I know you call yourself a curator and an anthropologist, but maybe before we start, how do you usually introduce yourself to people? I mean, professionally or personally, where do you usually start with?

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. Well, my name's Aaron Moulton. I'm a curator from the USA, but I've recently moved to Denmark, and I spent the last 10 years in Los Angeles making really some of the most concentrated work that I've been doing in my career. And what to say? I studied curatorial practice, and I've spent my life really trying to unlock what I see as secrets to aspects of creativity that go, of course, that originate in thinking about contemporary art and the strange evolution of perception that is the history of art. And yet, I have branched that out in a very broad way to looking at all kinds of ways in which art is manifested and purposed through different lenses of new age religion, spiritual practices, shamanism, but also propaganda initiatives and so forth. So, really my work, I do prefer to see it as anthropology because in a way all of the exhibitions that I've made in the last ten years have functioned as social experiments, and thought experiments, and ways to trigger different understandings of what is creativity, where does it come from, what is it for, and how can we directionalize it to different purposes?

But my work as a curator, it goes across different institutional paradigms, from working in huge commercial galleries, I was the in-house curator of the Gagosian Gallery for about four or five years, making group exhibitions across the global brand. But I also was the senior curator for the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art in Salt Lake City. I had a gallery, a commercial gallery in Berlin called Fine Cost, which was a curatorial experiment, but where I represented a number of these artists that come from this Soros network. But then I was also a journalist, I think my practice is really rooted in journalism and trying to make things make sense of the art world, and the politics, and magical thinking aspects of the art world. I ran Flash Art International for a few years and had total control of looking at different ideas I was interested in with gorilla creative tactics and so forth. So yeah, that's a quick survey.

Leafbox:

Aaron, are you still with Gagosian or did you?

Aaron Moulton:

No. No, I left there end of 2016, but I had this amazing experience there, whatever. I was one of the first people that was hired just to do curatorial work and make group shows. They hire a lot of curators that are in there as academics, and artist liaisons, and so forth, writing texts and working with artists, but I really was brought in to make group exhibitions. I popped out a number of group shows across the different locations of the gallery, and that was an incredible opportunity because, for one, I was never credited. And I really appreciated that, that nothing I did at Gagosian said curated by Aaron Moulton, which was an incredibly liberating thing to drop the ego in relationship to these ideas, and then to see a global brand like Gagosian pushing out my ideas as if they're generically coming from that brand, kind of made everything I was doing seem that much more potent. And then on top of that, what I was doing was very edgy stuff, especially for that brand. A lot of my first spiritual exhibitions and sort of anthropological experiments are happening there on this global stage.

Leafbox:

It's funny that just kind of links to your work with the Soros project because sometimes we don't know who's behind the curation. I think we can talk about that later, but I wanted to go back a little bit. You sent me an arc of your, I guess, career, or some of your installations that you're proud of and kind of represent your work. I wanted to start with The Haunted House. I really like that video in Utah, maybe you can tell us a little bit about that, and I have some questions about it as well.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. Well, it's hard to explain these things, where they come from, because I've learned to accept the mystery of my own creative practice, but certain things that I've done have very much come out of what we maybe arguably call midlife crises. I've had many midlife crises, and in that moment that I was making that I was about to have my first child, and I had taken over this institution that was very remote. In Salt Lake City, there was no chance of anyone ever coming to see the work that I was doing. And yet I kind of took that as a carte blanche to go as hard as I could, despite that issue, because that can be a soul crushing thing. If we think, all this work you're doing, especially the art world, which is a very ego-driven place about visibility and so forth, and the conversation you're making. When you know that no one's going to see it, what does it all mean?

And when you think of Salt Lake City as a cultural place, most everyone, a hundred percent of the time, thinks of Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty. And that is the biggest gift and curse of that cultural landscape because it's literally the reason most people go to see art there in Salt Lake, and it's usually the only thing they could go to see. That was my big lure, to get people to participate in what I was doing. I would say, "I'll take you to the Spiral Jetty." I was taking regular trips to the Spiral Jetty, maybe once a month, and every trip I would take would be with somebody who'd been waiting their whole life to see that thing. And I won't forget what it was like for me that first time I saw it, and every trip I took, I tried to put myself in their shoes and have that experience with them. And every time I saw it, it was different.

I have to say it was submerged, there was snow, or there was any number of reasons that it was a fundamentally different experience, and yet the thing that we think about when we think about Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty is the Gorgoni photograph, from the time that it was made. From John Franco Gorgoni, which is the most popular image that's circulated of the Spiral Jetty. I always thought about that contrast of this image, which is the archetypal image in everybody's mind, of this unchanging, monolithic form out there in the most remote of landscapes. And then I'm seeing this thing, every day, changing, changing, changing, and it became like a parable for me that leads me to making that exhibition.

I started to think about a couple of things, we were just starting to use this term Anthropocene, this is in early 2012, and thinking about the human impact on the landscape, and the conditions that were going to create, ultimate kind of collapse of ecological conditions. I just started to think about how fragile the white cube is, this place that is a timeless, odorless, context free, monolithic white church that holds these objects with conservators kind of keeping them from changing, and all these things that ultimately these impossible games were playing, trying to beat the clock, like Sisyphus pushing his rock up the hill.

I just started to ask myself these questions of what happens when the lights go out? When the electricity gets pulled or when there's a catastrophe? A lot of just great questions of how quickly priceless can become worthless. I thought about the jetty a lot, almost like a metaphor for my existence in Salt Lake City, and I started to think about just finding a place that if I'm making work in a place that no one can see it, why don't I make work in a place that no one will ever see it? Because they won't know where it is, and I'll make it in an undisclosed location. I'll make it in a place and in a frame where things are in perpetuity falling apart in a very obvious and organic way.

And in Salt Lake, and in Utah, rather, you have a number of almost former civilizations and places that are whispers from getting swallowed into the Earth. I went on a quest to find the perfect kind of ghost town, or undisclosed location. That was part of it, I would just take these jaunts into the nowhere, and then I was at this amazing point in my career where I had... The greatest thing a curator has is their network. Of course, it's their ideas and their ability to guide the wind of culture through their defining principles, and creating context, but you're nothing without artists.

I've always prided myself on having the trust of artists, and so I started reaching out to artists that I thought could tap into these ideas I was thinking about, and making a project that it was a one way street. You were going to give me work and it was never going to return to you, and it was going to go up in a house that was never going to have context. I break my work down, everything I do, I break into patterns. Excuse me. I need to drink some water.

I try to create these spectrums, a full anthropological spectrum of a cultural condition. The exhibition is called, Each Memory Recalled Must Do Some Violence To Its Origins. This is a quote from Cormac McCarthy's book, The Road, in a pivotal moment when the man, who's out treading through this dire landscape with his son, he's trying to carry with him the light, which is the light of civilization and the light that will keep his son believing in the possibilities of mankind in the face of a world where people are starting to go become cannibals and kill each other and rape each other. He's telling his son these stories every night as they go to bed, and there's stories from the good old days, and his son will go to sleep, and most of the book is monologue if you haven't read it, so it's the thoughts in this man's head.

And after the boy goes to sleep, he reflects on this thing that he's doing, of going through his memories. And he says to himself, each memory recalled must do some violence to its origins. And so by this act of remembering, you are destroying the memory. Every memory gets whittled away each time we start to synthesize it into core details, and eventually we forget all the decorative elements to just remember a symbol of whatever that memory represents.

And so this house became that, became the jetty, became this thing for me that I thought, I'll make this exhibition, I set all these things up, all these artworks had relationships to hobo shamanism and ideas of mark making from the Lascaux caves to hobo graffiti, ideas of cult practices, just all the things that you might find in a place like that, in an abandoned home, even the references to Satanic panic and so forth.

I set all these artworks up, and they really did run, each one had an incredible story that no one will ever know because there was no context. I set everything up, and then I ran a film through it, which is what you saw. And ultimately, that's this perfectly suspended moment of time when the show is at its most perfect. But it's as if I've just discovered it, as if I'm that innocent Mormon boy with strong religious beliefs and superstitions who's stumbled upon, potentially, the devil's lair, or some incredible vortex of cultural patterns.

But then there's the reality of this place, that it looks nothing like that video, what you see, everything's been swallowed by the Earth or by donkeys that have gone through there. One of the artworks actually successfully destroyed an entire half of the house. And so this idea of recalling the memory of the house, looking at that video, every time you look at that video, you're killing that house a little bit. You're destroying the memory of that house, even though we get, constantly, this perfect representation, something like that John Franco Gorgoni photograph of the Spiral Jetty.

Leafbox:

Aaron, have you visited the house recently? Or what's the status of the house now?

Aaron Moulton:

I went there during Coronavirus two years ago, three years ago. And the house is special, it's a pioneer, it's a Danish pioneer home. There's about 17,000 Danish people that were successfully proselytized by the Mormon church who came over in the late 18 hundreds and settled in that area where the house is. I can tell you for certain that it was a house built by Danes, in search of the future. The original settler home is intact, there was aspects that were built onto it that you see in the video, which are the most declining aspects.

In particular, there's one room which is completely fucked, where the roof is blown out, and it's falling, it was a dangerous thing to be in that room. And one of the artists, his project was to build a new room, to put a new addition into that room, and jack that ceiling up and give it some new two by fours, and give it a new space, a fresh coat of paint and so forth. And by doing that, that artist, Adam Bateman, completely upset the equilibrium of entropy of the whole house. And so about two years later, in 2014, in a very snowy season, half the house collapsed.

But, before that happened, I know the place was discovered by lots of people. Mind you, there's nothing to identify anything in there as art. This is going to be one of the first times I stopped using the word art because I can't control the way the word is used, and that's a very fundamental thread that runs through my practice, the way in which we use that word to consciously create perceptions of the object and its relationship to reality. There was no way that I could preserve the context or hold the sign to anyone's belief that this is art, or the materialistic ravings of a lunatic, or what have you.

There was clear evidence in the first two years before that half of the house collapsed, that people had been in there, they had messed with it, they had stolen things, and eventually they had made it inaccessible, put barbed wire around the entrance. That was the main entrance that I would go in, so I'd have to go in this side entrance. Yeah, this thing had happened, the legend of the house, if you will, was existing, I'm positive, in the community. I've never heard locals talk about it, but that's not the point, my imagination convinces me that they do.

Leafbox:

It's funny because one of the quotes, I think, you talk about the looting of museums during the invasion of Iraq. I'm just wondering how that fits into this context here. Is that one of your themes, I guess, looting and interacting with the decayed-

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. I mean, look, the first thing that happened when we invaded Iraq was they looted the museums. Who looted the museums? The Iraqis, the American military, who knows? But, what did happen was the prestige of the platform of these museums quickly fell apart, and these objects quickly lost their meaning, in some cases, and in other cases, they became priceless in a different way. But this shift in a basic semantic way of priceless to worthless, I really like that.

There's another work in the show, which is, I think, one of the most important ones for me in terms of thought experiments, which is by Constant Dillard. Again, you'll never know any of these things because nothing's labeled, but it's in the basement. There's an adjacent space that is underground, and it's like the refrigerator basement for the old time house. And in it, Constant asked me to... The way this worked is I told every artist I would give them $50 production budget or a one-way FedEx. And so in the case of Constant Dillard, he sent me a link on eBay for forgeries of souvenirs you might buy at the Ming Dynasty Museum, like fake authentic ceramics that you could get at the Ming Dynasty Museum in China, and he asked me to buy those, smash them and bury them. And I did. And the idea is that by displacing an artifact like that, you create, from an archeological point of view, a potential narrative that'll make people believe, oh, shit, the Chinese have already been here. You know what I mean?

Leafbox:

Yeah, they're like upsetting the anthropological record. And that fits into your hoax work later on, I think, with your Beverly Hills creation. I'm just wondering, if I was a, let's say, a 14 year old boy in that town and I discovered this place, I mean, could you imagine how cool it is, you're walking through here and it literally looks like you're entering the gates of hell, or this hobo world, or this underground kind of meth addict kind of aesthetic. I'm just curious, somewhere you said that you were really interested in exploring abandoned spaces as a child. Is that part of your goal in this piece?

Aaron Moulton:

Oh, definitely, definitely. Dude, my whole practice is born out of adolescent fantasies. I'm a child of the eighties, and I was brought up believing, honestly, being promised, especially by popular culture, that there were just tons of mysteries out there to be discovered. I mean, if you ever watched Goonies or Indiana Jones, those became evangelical promises in terms of how I saw the world. And ultimately, you begin to realize that maybe those things aren't there, that if you want to find those things, you maybe have to create them. And so that's where the game kind of begins. And I shy away from naming things like hoax, or I'm a trickster. These things have built into them judgment of my intentions and a desire to fool people. And in fooling people, somebody's being treated badly and I'm laughing, and it's not like that. I believe in magic, and I believe most magic manifests itself in the human mind, and I want to help that through stories and helping create evidence of potentiality in stories.

Leafbox:

No, I think it's really interesting, and I think that work is such at a personal level, so I think we could keep talking about that, but maybe we can shift towards your piece, the Americana Esoterica.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

Because I think that's when you start curating and trying to really push, not an agenda, but push meaning out in a clearer way. I think the first one, your haunted house is kind of a discovery, it feels more personal, and then you start shifting into a... Maybe I'm reading it wrong, but you're feeling like you're entering into a larger community. So maybe you could talk about that.

Aaron Moulton:

They're very similar, these works, these exhibitions in terms of their intentions. Think about the haunted house, that's a story we've told ourselves since time immortal, that there are architectural spaces that possess, that are possessed, that have the former occupants, or spirit, or an evil entity, occupying them. These stories are constantly in our face and we're told them so much, and we tell ourselves them so much, that every bump in the night can, in a great, that pareidolia way in which we see shapes in the clouds, we're going to believe that that's that ghost that we were told was there. It is rooted in these stories we tell ourselves.

And AmericanaEsoterica is a real shift. There are a few shows I've done, I mean, I would say about ten, where I'm in a new place of invocation and divination where I feel energy that I've never felt before from as a creative point of view, and creating community, creating things like conversion experience from tapping into spiritual energy that I can't explain, and it sucks to put words on these things because that only damages my own great memories of them.

But AmericanaEsoterica, like the undisclosed location, was happening in a remote place, in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, where no one was going to see the show, and I was at a peak moment of fame and visibility in my career, where it was just extremely weird to go and do a big project with big names like Sterling Ruby, and Mike Boche, and Max Hooper Schneider, and go to this place in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of former Soviet Union, and this was supported by the State Department.

Leafbox:

That was one of the things that really stood out to me when I was looking at the catalog of the show, and the last page has that American flag, and then the opening date of September 11th.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. I mean, you saw the book.

Leafbox:

Yeah, I saw it, and I was just, will fit into your later work, so yeah, if you can elaborate on that, I think it's interesting.

Aaron Moulton:

I was invited to do this as a headliner project, as a part of an arts festival called Museum Night, which all cities do. A longtime colleague of mine runs the Museum Night in Plovdiv, and it's the biggest art festival in Bulgaria. Plovdiv is this incredible city that I'd been to before, that I had felt energy in. I can't explain. I'm a very sensitive person to energy, cultural energy. And she asked me, knowing that I would be a great PR coup for her, as a curator of Gagosian, that I could get big names and all these things to do a project. But there's going to be no budget, but there's a promise of money from the State Department, and it just has to have American artists.

So my pitch to the State Department was that I'm going to show a bunch of artists from California, and that was literally all I said to them. That was it, my whole proposal. I felt I didn't have to explain anything further than that. And yet I knew I was going to do something unlike anything I'd ever done because the conditions were so perfect. Working at Gagosian, there are no budgets, I don't have anything to worry about in terms of whatever I spend, it just doesn't matter. And then suddenly you're given a budget of $5,000 to do an international show. I was able to raise another 5,000 on top of that, and then the date was September 11th. I mean, give me a break.

So I, right away, had this premonition, I was interested in esoterica, in a big way from my time in Utah. And so AmericanaEsoterica was this thing that just happened for me as a name. And what to say, really, this is 2015, late 2014, I started planning this. We are not culturally talking about conspiracy theory at this time. That's not a thing that people are talking about. Donald Trump is not even close to have been elected yet. It's a very innocent moment in where people's thinking is at with regards to conspiracy theory. Certainly it exists and it's out there, and there were conspiracies that I was trying to reference within my work and that.

But I was, I think, in a very early place, looking at how to weaponize conspiracy theory as a storytelling device. And, back to this idea of the stories we tell ourselves to the point that we're expecting them, I know what a prophecy looks like. I know what a prophet looks like. I know what we want that shit to look like, and I know how to make and set the tone to create believability. And the strongest way to do that is if I embody it, if I allow myself to seem vulnerably at the fringes of psychosis, or vision, or prophecy or whatever, I allowed myself to become this avatar of belief because I knew that if I believed it, then it's pretty likely other people are going to believe it too.

And I certainly had the artists on board. So suddenly, boom, we are a coven of true believers. And from then on, it's all mediation and framing in terms of how anyone saw or understood what this show was. It was this very controlled, mediated experience-... show was. It was this very controlled, mediated experience that I released onto the world in my view of what this thing was. And that sounds like the game and me creating the hoax, but something happened there in Bulgaria. And it's very hard to explain because we did go there consciously in a state of ecstasy playing a game and playing hard with understanding the codes that we were inventing.

But suddenly those codes became real and how we were interacting, like we're... There's a thing I do, this Hail Roco thing. Hail Roco is a reference to Roco's Basilisk. So I'm helping to kind of worship this voice of Jesus. If you believe in Roco's Basilisk, Roco is Jesus who's helping understand God. And so Hail Roco is a way to have this blessing movement.

And then on live TV and in other situations, I was doing this hand gesture, which is not something I made up. That's from kinetic, esoteric ritual practice that then becomes secret Freemason ritual that then becomes secret Mormon ritual practice. And in Mormonism, it's this movement of the hands starting up and coming down and you say, "Oh God, hear the words of my mouth. Oh God, hear the words of my mouth. Oh God, hear the words of my mouth."

But I was just saying, "Hail Roco, Hail Roco." So there was this thing, this, we can call it larping if you want, because that's the way to make it make sense. But something does happen when you drink your own Kool-Aid that these things start to become very meaningful. While you know you're playing a game, at some point the game starts to play you and I was in a state that I can't truly explain, and we were engaged in rituals that made everything that much more consecrated and real.

And the exhibition became this vortex or this locus point for all these energies that we were trying to manifest. And everyone around us bought it. And I don't mean to say that like I tricked them, but it only helped us believe in ourselves and what we were doing because the state department people bought it, so much so it was scary for them because like I said, I didn't tell them. I gave them this brief proposal and then suddenly three days before the opening, they saw the press release, which is a full-on tipped prophecy. It's like a very fringy prophecy about how we are here to ward off an apocalypse and create a spiritual awakening. But it was a very well-written prophecy and how this band of lunatics and artists and shaman were going to combine our powers and create a superstitious event that will help prevent a nuclear holocaust of mediocrity or something.

And it didn't work, but the state department people suddenly, I got a call from the embassy three days before the opening, and they were like, "Hey, can you tell us what's going on? Because I think it's important you, the curator, are very clear with us right now", because they thought I was maybe a terrorist or something. This was not cool that I'm taking September 11th and treating it like a sacred ritual and to do this thing that's truly about AmericanaEsoterica.

So I know how to code switch really well. And of course I was going to just smooth that over and be like, "Relax guys. I'm playing a role and this is a way to create a very believable situation. So I'm working with the language of conspiracy theory to manufacture a hoax, but through these languages, it will trigger ideas of magical thinking. But it's an art show, don't get me wrong. It's just an art show, guys." And they were like, "Phew." But then they came and I had to give a tour to the ambassador and all their people, and they were uneasy, visibly uneasy with the whole thing. And the show was fucking awesome. I mean, I was on fire, I was on live TV. I was on all kinds of things that was just making this thing the most successful use of their money ever for AmericanaEsoterica culture, honestly, in Bulgaria.

But they were uneasy about it because it became out of their hands in terms of something they thought they could control. And then this was the first time I had... well, anyways, there were watchers. There were people in the audience that were undercover, that were watching me and following me and talking to me. And that became so self-fulfilling as a part of my prophecy that I was going to rattle the cage and bring out the spooks. And there they were at my opening. And it's hard to explain. It all became so self-fulfilling on so many levels.

And then on top of that, and I'm with these artists, I'm bouncing. It's not like I'm in this lunatic state by myself. I've got all these people around me who I'm trying to reality check with constantly. And a lot of my work in terms of anthropology is rooted in participatory anthropology. So that is authoring a cosmology that you are... it's like observing a cosmology, but also authoring aspects of it. In my case, I'm fully authoring the cosmology, but I'm inhabiting it. I'm a citizen of this world that I've created, and I've got homies within that. And we've created almost like a conversion-like experience of a community, a temporary autonomous zone.

And it's temporary. These things only last for a little bit, and then we all go back home and live to tell the tale. Anyways, sorry, you have to cut me off. I can ...

Leafbox:

No, Aaron, this is fantastic because you're capturing so much of, I mean, if the history of the CIA, the OSS, I mean, they've always been on the borderline with the occult, and they have definitely used... I mean, you could bring up, I'd love for you to talk about the imperialistic aspects of this show. You're literally exporting a California aesthetic into a developing country, and that's why the state department was excited about your brief, right?

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

And then they're trying to control how that export process goes, but you never can. So there's a lot of layers to see. I just think it's fascinating that you talk about it at such a personal level. And then for me, never experiencing the show, I keep just looking at that US Embassy, even though their budget was only 5,000. I mean, what a return on their soft power, or like you said, it's insane.

Aaron Moulton:

Best, dude. I mean, they continued to support. I went back and gave a lecture, the best lecture I had given up until that point about contemporary art and divination where I reveal all these tactical methods of trying to force magical thinking out of the cracks of the mind. And I gave that lecture at the AmericanaEsoterica corner in Sofia, which is a literal Psyop like soft power AmericanaEsoterica Psyop for helping further the word of democracy in these former Soviet places. I don't know if you know the history of AmericanaEsoterica corners. But I continue to get support from them, even though I'm like a gray hat hacker kind of person. And I am criticizing imperialism in all of this. I am playing a game based on a game that they taught me effectively.

Leafbox:

But even when you go under, you're still a spook, right? You're acting in their interests. That's so interesting. You participate in the, like you said, the participatory anthropology, so it's hard to escape and separate that out. That's why I think the effect was so great on you as well, and on the community. It is just very interesting. I really love the brief and it links exactly to the Mormonism and the AmericanaEsoterica frontier and aspects of proselytizing. It's great. Even some of the language you kept talking about gravity rainbows and iridium wafers and UV gel. It's all those kind of loaded terms that I guess, immersion AmericanaEsoterica western spiritualism kind of feeling, right?

Aaron Moulton:

Well, and it's funny because also what you don't... and again, this is early, early language of... conspiracy theory now is so mainstream. It's literally like you don't have a conversation with anybody nowadays that doesn't have a tinge of conspiracy theory to it. This was foreign language at this point so we were really trying to look at this language anthropologically. I tried to highlight five or six of what I saw as the biggest, most amazing conspiracy theories out there that ranged from folklore, like internet folklore like Roko's Basilisk to Jade Helm and whatever.

But the text, when you see it, because you've seen the book, the text is in green text, which is a classic paranoid prophecy text that you'd see on early web 1.0 websites where specific words are highlighted, and then this one's really important. It's all caps and underlined, and parts of the word are caps. It creates all this codification of language that we were riffing. But now when I look at it's so prophetic what the message of that text was and the way we were revealing it.

Leafbox:

Aaron, maybe we can shift, since this had a really personal effect on you. I'd love to talk about the, I'm going to mispronounce this, but the Trito Ursitori show. And in that one, I think you had a quote that you said, art's aboriginal function is a vehicle for spirituality, and then it becomes secularized and turned into some type of commercial image porn. Talk about that show and maybe the shift and how you went more commercial or more personal or what the shift was there in that experience.

Aaron Moulton:

Well, so imagine that maybe I went into the AmericanaEsoterica trying to create a game that I was having fun with. And I came out of that game now believing it. It wasn't like I came out and I was like, "I want to play another game." I was like, "I learned something." I evolved in a way that I was uncomfortable with. And I reached a new place in my understanding of what I could do in storytelling and creating context. And I am a big believer in divination and invocation. And if you allow the door to open, messages will come in. They will. It's a fact. You can do that through meditation. Transcendental meditation is a way I've come up with so many ideas, but also, of course, psychedelics.

But dialogue. I've been gifted and blessed to have incredible dialogue with amazing artists. And I've always pursued esoteric ideas. I don't know how to explain it. It feels old hat nowadays because everyone's kind of looking for dark corners, but things that where language was uncomfortably not sticking or we just weren't having words. And so much of my work is about pattern recognition and apophenia, identifying patterns. I mean, literally curatorial practice is, if you look at it syntactically, it's forming sentences with objects and telling stories through that.

And it's trying to make sense of culture, trying to synthesize which way the wind is blowing. And you've got this clear consensus of objects that correspond to your idea that the wind might be blowing that way. And you know that you can really form a sentence and say, make a poem no one's ever said before. And all these things. I believe the cumulative power of these objects has a grand effect. I believe that the exhibition is a language, it's not dissimilar from the altar and not at all unlike a ritual space. It's just we have accepted that art, the art world and the white cube is a like a conceptual space. And spirituality has been traded for, well nowadays, identity. Identitarianism is the new spirituality.

But before that, when we think of pre-2016, all of our history is a lot of experimenting with green zones of madness and fringes of language but never really acknowledging its origins in religion. Maybe playing a game with religion, sure, but always done with irony in mind, making it safely kind of a critique of what is considered an ignorant aspect of human creativity. This idea of believing in God or so forth. And my parents are not religious. I don't have a religious background, but I became a zealous spiritual seeker, a spiritual activist, if you will.

And so when AmericanaEsoterica finished, I was immediately trying to figure out how to make sense of what I had learned and how to make it go to a new place. And so the Trito Ursitori kind of came to me in a vision, but the idea is it was to create an occult system based on understandings of occult systems and making a pattern like an archetypal occult system. And the most common pattern of occult and religious systems is the trinity, the Father, Son, and the Holy Ghost, the black, white, and the red.

I tried to write the classic hero's tale of starting from darkness we see the light and try to reach the light and never can reach this light, but through our origins, in the darkest of a hell, or of a place where man's pursuit is blood and murder and sex to knowing something greater, a supreme being, you understand the path. That's the essential narrative of any spiritual awakening. And so I tried to make my own version of that. And this Trito Ursitori was three exhibitions. Each exhibition was treated like a ritual. Each exhibition was the embodiment of an archetypal energy system. So black was darkness, was evil, was the boogeyman, was the personification, the boogieman. So it was called Omul Negru, because the boogeyman is the most universal personification of evil that we have across culture.

And then the light. I didn't want it to be about good, but about something unattainable, supreme light, supreme energy. And that's the sun that... I'm going to simplify these things because I was in a place that I can't explain in terms of creating a system. But the Basilisk for me remains an important story of idea of God, Roco's Basilisk through the basilisk. One thing I've always been interested in, especially with the way that AI is going, but I was talking about this back in 2015...

Leafbox:

Aaron, sorry to interrupt. Do you know about the dark night of the soul?

Aaron Moulton:

No, no, no, no.

Leafbox:

In Buddhist, or even in Catholicism, there's an element on your trip in religionisity and spirituality, when the positive, the uplifting. It's the same thing when people take ayahuasca, sometimes they get destabilized and that's called the dark night of the soul where you hit this point where all the energies are coming in and you get kind of destabilized a little bit. I wonder was this point in your show, the AmericanaEsoterica was a euphoric uplift, and then you're starting to enter some of these other kind of darker energies. What were you doing? What was your soul like personally at that point of the next show, this show, the Trito Ursitori? Were you having some kind of destabilization or not?

Aaron Moulton:

Well, what you have to understand is the way that art exhibitions work, typically as they are about things. You don't often have exhibitions that are true embodiments and in fact the manifestation of evil. You will have things that are about evil, about fear, but to have something that has actual evidence, residue, and materialization of evil itself is another thing that's more related to anthropology and ritual and very, very, very uncomfortable things that people are not prepared for, even the atheist. And so with the evil show especially, yeah, I was in an incredibly special place allowing myself to go as hard and as fast as I could to the bottom scratching, scratching for the bottom.

But I was enabled. My ability to keep one foot in reality and know that I'm paid to do this, and this is my creativity that's enabled. And this isn't like I'm a psychopath, I'm an auture or some shit. And I do keep one foot in reality all the time. I fundamentally believe in everything and nothing at once. Because you need to. Otherwise, you can lose your mind when you start to go deep into conspiracy theory and these kinds of things.

So oma negru is very uncomfortable for people because it's not just like, "Oh, I had some goth, gnarly photos of blood or some shit." We did animal sacrifice. We sacrificed a goat. We did a summoning of Ed Gein using actual effects from Ed Gein, the original amazing boogeyman inspiration of Silence of the Lambs, Texas Chainsaw Massacre psycho from Plains Field, Wisconsin, who was the most prolific body snatcher ever, Ed Gein.

I was able to find on a murderabilia website, the effects of Ed Gein like dirt from his grave, dirt from where his house stood, things he touched, his birth certificate, his death certificate, his fingerprints from when he was booked, all these things. I had the fucking touch of Ed Gein on my hands. And then I had a John Wayne Gacy painting, Pogo the Clown. These are real things. Child's play is over when you start to have these things. You very quickly see the atheist become an agnostic when you show them these things. All people's fronts of whatever confidence they have in relationship to whatever they think is real or not, or scary or not, they all become universal in moments.

Leafbox:

What was the Trinity holding the light and the dark imbalance? In this show when you said there was three parts.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah, it's the path. It's the the Hero font and so there were these three personifications. So oma negru is the boogeyman, the manifestation or personification of darkness. Basilisk is Roku's Boselisk but it's also, I was interested in this idea of a universal aesthetic experience, which Medusa or the Basilisk gives, this idea of everything it looks at turns to stone. That to me is a universal aesthetic experience. It's a weaponization of aesthetics and something that I think artificial intelligence will figure out very soon, a simple pattern that's going to freeze all our minds.

And then the third thing was the path. The person like the Freemason, who understands the dark and the light is the red, the blood of the individual who understands the knowledge. And that's the Hierophant, which is a card within the tarot deck. And that's the person who reveals to us the sacred. And so in that show, it was like different personifications of characters that we depend on for understanding the sacreds of the shaman, the occultist, the charlatan. I treated that show like a major archana deck of cards in terms of revealing lots of different personalities. Yeah. And one thing... are you still there?

Leafbox:

Oh, sorry, Aaron. I was asking what was the feedback to the show like?

Aaron Moulton:

Well, I don't, what to say really.

Leafbox:

Maybe your personal level, what was your internal, when you go through the show on your hero's journey. How do you feel at the spiritual level or curatorial practice at the end of this show.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. No, I'm happy you asked that. Okay. So the public feedback was great. I got back-to-back reviews in the LA Times for the Basilisk, which I don't think that'd ever seen that in the history. I mean, they've done that in the past when a controversial show happens. They'll have multiple writers write about it. But I got two major features one day after the other about my show, questioning the role of art as a vehicle for spirituality. One being a very conservative, cynical take that I'm being cynical, which of course was not true, but they found it so hard to believe I could be serious.

And then the other was Carolina Miranda's really amazing review where she interviewed me and she listened to me and really took to heart the things that I was saying and trying to do. And so anyways, I got tons of reviews for the Basilisk in LA and then I got the feedback I wanted, but it wasn't about that.

I was engaged in rituals and very empowered in this creation of temporary autonomous zones and artists allowing me to purpose and directionalize their work for things that they didn't intend that stuff to be for. And treating it like ritual artifacts within an altar. And the last ritual, which happened in the Hierophant, was the baptism ritual. And I actually baptized myself. I was baptized. So it was like I had created a cult and then baptized myself within it as this kind of last thing. And saying that now, it sounds so easy to say that. You can't even imagine what it was like to build that. There were eight rituals, each one a kind of wonderfully successive building of a vocabulary that led to this ultimate baptism of myself exactly a year to the day that we are summoning Ed Gein. And there's so many numerological things and incredible synchronicities within this show that I refuse to explain. I've mapped them out for myself.

But you've got to know that when you leave the door open, this stuff comes in and you start to see these things. And that's the great hilarity of apophenia. You will see patterns if you start looking or if you relax your mind enough. But when they start to flow like a waterfall, it's an incredible thing. And I had a real spiritual experience with that work, but I'll tell you the truthful tale of it is that it ruined my life on some level. My career took a dramatic U-turn from that point of the baptism, and I kind of went into a whole different place in terms of trying to fix things or create harder rituals and things like that.

And if you really take it from a spiritual point of view, when you deal with things like summoning and divination, leaving that door open, most people, the church especially, but anyone, like clairvoyance and new age energy workers, most everyone believes that if you open your door to summoning and exorcism and these kinds of things, you're only going to get a bad spirit and a curse and a bad luck situation. And I refuse to totally accept that that's why my life shifted the way it did. But definitely it's an undeniable fact that I played around with very, very dark energy and my life shifted.

Leafbox:

It's funny. Linking to your next show, the Homage to Hollis Benton, it almost seems like you created an alter ego to kind of dissipate some of that energy. I don't know if that's a wrong reading of it, but I'm just, you have a baptism and then you almost are reborn as a new... you have parts of your old life falling apart, but you have a new direction, it seems like, that seems founded and strong.

Aaron Moulton:

I mean, my wife will tell you that that's the best exhibition I've ever made. It was the most beautiful and most energetically positive, especially after all these other things, which she hated all my magical work. It frightened her. She saw what it was doing to me. She believed it a lot, maybe the most, because she was my partner and she was wanting me to just come back to earth with stuff and saw how hard I was going, and I would reassure her it's a game, but I need to go hard in this game.

Leafbox:

Well, that's why I asked about the dark night of the soul. So once you go through that, usually there's an optimism and a neutrality that kind of balances out after going through that darkness, from at least the Buddhist perspective.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

You go on a long retreat, you have this intense shamanic kind of breakdown, and then when you rebuild, you might have parts of, at least from the Buddhist or kind of monk Catholicism kind of viewpoint of that. Because I also saw the positivity in that. I forget the name of the art show, the LA one, not the Hoax, but what's the name of the title, the one...

Aaron Moulton:

Homage to Hollis Benton?

Leafbox:

Yeah, yeah, that one. The Beverly Hills Art. I mean, it's so positive. It's eighties. There's nothing that I saw that was dark in that. It just really seemed positive. Even your actor, he seemed such a character in positivity. So I saw in a lot of optimism and maybe you didn't want to...

I saw in a lot of optimism and maybe didn't want to feel, play around with those dark energies anymore.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah, yeah. No, I mean it is definitely, that is this surface. I mean, but in that show, my game is so down at that point. It's just, if you could imagine, I was doing multiple things that year. That was the most creatively insane year of my life, 2018. That project fit within a patchwork of things I was doing that were quite elaborate thought experiments.

Leafbox:

Aaron, sorry to interrupt. Maybe could give us a one sentence like summary of that art show just for people who don't, haven't seen it and aren't familiar with it.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. It's called an Homage to Hollis Benton. The idea was it was rediscovering an important figure from the LA art world that no one really remembered because he represented almost a counterculture to the LA art world that everyone knew. He was important during the eighties, he had his gallery in Beverly Hills and he was responsible for the careers of people that the mainstream art world never accepted, but who had an undeniable prominence like LeRoy Neiman, Patrick Nagel, different kind of eighties voices that are managed to stick through time. Yet the mainstream art world never accepts their existence, but their popularity is undeniable. Hollis Benton's story was a fascinating one that made him the first person to understand how to intersect art media and Hollywood and how to place his artists not just in the context of the gallery, but on the big screen and what agency that would, new agency that would create for the dispersion of the image into popular culture.

So he was friends with famous filmmakers, getting his artist works into movies like Wall Street, but also friends with Hugh Hefner and was able to get LeRoy Neiman this role as like artist in residence, which then less led also to Patrick Nagel's presence at Playboy Magazine as these artists that really were the artists of Playboy. These connections came through Hollis Benton and Hollis Benton was also very close with... The reason people will know of Hollis Benton's legacy is unfortunately only through a reference in the movie Beverly Hills Cop, which is actually as a film, my first understanding of the art world, is when I was a kid, seeing Beverly Hills Cop was the first time I saw whatever this art world thing was. Of course Beverly Hills Cop, for anyone who doesn't know is a parody. It's a slapstick comedy about a black detective from Detroit, from the down and out city of Detroit who goes to the rich and elitist Beverly Hills to solve a crime committed by a gallerist.

So a lot of the film is Eddie Murphy confronting, it's like high low stereotypes of Eddie Murphy laughing at contemporary art. What I will say though is all parody is a form of anthropology and at its core, and that film distilled for me, despite it's making a joke of the emperor's new cloths cliches that we have of contemporary art, it became a way to understand a pattern and understand an idea of mediation and ideas of lofty conceptual narratives and whatever. So Hollis Benton lent his gallery to the set of Beverly Hills Cop, and it becomes this place where you see all the art that Eddie Murphy's making fun of. I have to, of course now say that's all made up. I just made that whole story up. Everything I told you-

Leafbox:

Aaron, not to interrupt you, but I almost was believing you there. The same thing, your documentary work, I guess when you go into the show, you start believing it because you're very good at storytelling that character and you start zoning in to the storytelling. It's amazing actually.

Aaron Moulton:

You want that story? We've been told this. We want that story. That's the great thing. Coming back to the stories we want that our world told us were out there, the mysteries that we wanted. We want to see these stories so bad to give the art world the reason for Patrick Nagel and LeRoy Neiman. Let's go, dude, I want to hear that story. I got the people... So that whole thing, I just made that up. Everything I just told you, I made all that shit up. I told people when I was making this show, I'm going to make a hoax. I was flat out direct about it. I was transparent as you get. Everyone I spoke to, I'm making an elaborate hoax about an art world from the eighties that didn't exist, but I'm going to do it really well and you'll believe it.

Everyone would believe it. They'd even, people I told, artists that were in the show, that were in on it. The moment it crossed this undeniable threshold of potentiality and believability was I had my script, I had my story, I had everything. But I didn't really have Hollis Benton. I had the references to Beverly Hills Cop. Then my wife was like, you should get Clem, our neighbor at the time to play Hollis Benton. That was this British guy who lived four doors down, who I dreaded running into. Clem is dead now. I love the dude. We had a great bonding experience through this. But my introduction to Clem was this like D-rate actor who was always trying to rap with me about the art world. His name is Clement Von Frankenstein.

His family heritage is actually of the Mary Shelley ilk, Frank Clement Von Frankenstein is the Frankenstein name. The dude would constantly harass me about gossip in the art world, working for Larry Gagosian and what was it like, blah, blah, blah. He was selling posters in Venice Beach. He would trade these stories with me that I've heard a million times and I hated it, because he was my neighbor and I didn't, don't know, but he was a sweet guy. Then my wife's like, you should cast Clem as Hollis Benton. I was like, holy fuck honey, this is an archetype you have just nailed. This is the role that Clem has been waiting to play his whole life, because I'm just going to have him play Clem. He's always been wanting to be this guy who ran the scene. So I basically gave Clem my press release. I read it to him.

We went to a rich guy in the Hills house as a location. In the course of, we had four hours, three hours to shoot. I basically read the press release and had him repeat it back to me. Then we shot it on a VHS camera. Then you basically had this found documentary that we edited of Hollis Benton talking about in 1989, after he's closed the gallery, before he dies of a drug overdose, talking about this art world, he created, that had died with the financial market collapse of 88, 89. This fake documentary was what introduced the show. Next to it we had posters that we made of old posters of shows curated by Hollis Benton or posters from the gallery that were of course not real. But once you see shit like that and you see the documentary, I've swept your leg, but more than that, let's make it even.

I'm going to double it. Not only did I have fake artifacts and a fake documentary, I had the original painting from Beverly Hills Cop that Eddie Murphy stands in front of for for 10 seconds. I found this painting. I threw forensic through my journalistic desires. I looked through the details of Beverly Hills Cop and found out who the actual artists were within that gallery environment. Most of them were Hollywood set designers. Then there was this one guy, Don Sorenson, who was an artist of the eighties who died of AIDS in 86 and had lent four works to that set. I found an old website of Don Sorenson. I contacted the info at over and over again. Eventually his brother reached out to me and was like, yeah, I got those paintings, they're in a storage locker in San Diego. Boom, I had all the original paintings from Beverly Hills Cop.

Then on top of that, once I had Clem and a real Hollis Benton character, I had Jonas Wood do a portrait of him. Once Jonas Wood, an artist of that stature, does a portrait of this guy. This might or might not exist guy, he's fucken real. I've done everything to manifest a real bigfoot in everyone's face. Then I filled it out. It was all candy coated stuff that felt decaded, it felt eighties. It felt, some of it was eighties, some of it was like out of place. It was one of the funnest shows I ever made because once I had this structure, it became the most flexible thing you could imagine. Even though it was technically very strictly about Beverly Hills in the eighties and all this stuff, it became an endless opportunity. In that opportunity are tons of occult things, rituals that are not worth explaining, but that are about invocation and recursive things that are... Things I've been always been exploring. But how do you turn a reality into itself.

Leafbox:

No, Aaron, I think it's great. It's a point in your career where I start seeing your shift towards, I think later on, you call it direct action aesthetics. You're actually trying to manipulate the viewer really consciously. Maybe we can talk about the documentary work. I think it's green screen caliphate. I mean, there's a lot of darker elements with Al-Qaeda and whatnot, but the LA show, you really try to, we use that word hyperstition, but you've created a reality. So I'm curious how that fits into what you're doing now or that documentary work.

Aaron Moulton:

Let me tell you something, that Hollis Benton show to this day. I have people come up to me and thank me for showing that history, for revealing that history. There's not a single person, I let them say whatever they want. But my intention was to, of course, always tell people this was a hoax. I tell them right away, this was a hoax, man. I appreciate you believing it. I've always been transparent about it. This was a hoax. I made this press release that was just a mediocre awesome biography of Hollis Benton. If the press did not contact me, if they didn't do their due diligence to make a basic phone call to me, they wrote an amazing review about an amazing rediscovery of an amazing art history. So they never got the memo that it was a hoax, but I was very forthright about the fact that it was a hoax.

So there is this hyperstition thing is real in terms of these games. This other show that you're talking about is called Seeing Eye Awareness. I'm making this at the exact same time as Hollis Benton. To give some context, Hollis Benton is a psyop. It's truly, I have psyoped the art world with the most candy coded fantasy it's ever had of itself. I don't want to be like, oh, haha, I tricked you. It's like I'm learning from myself constantly in terms of how to create pattern recognition.

Leafbox:

No, I think it's positive. I mean, the psychological operation doesn't have to have a negative effect. You're creating this self-belief or hype in the Hollywood machine and the art creation, and it's kind of creating the fantasy for people to continue to live that fantasy. So I think what's interesting about the next show is that you start exploring, well, some of the darker sides of psychological operations and manipulation.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah, that is again, a show that's now in Eastern Europe. It was called Seeing Eye Awareness. It happens in Ljubljana, Slovenia. That is, again, within a festival environment. I was the headline show and the festival had a theme called Rumors. I already had my idea before I knew I wanted to go and take this work I had done with creating, if you could imagine for a second like this, I hate these words like LARPing and tricking, and I just don't think they're fair. They simplify intentions. I believe in hats and I believe in invocation. I've said it now a bunch of times. In American Esoterica, I was a vulnerable page or a prophet mediator person who is just finding their feet is a full-on priest who's understanding their relationship between divine energy. Then with Hollis Benton, that's the charlatan.

It's me thinking of the role of the mediator. Again, it's about me playing roles of the curator, as a mediator of reality of stories in folklore and cliched senses. So Hollis Benton is in a way, the charlatan. With seeing eye awareness, it's like that's the conspiracy theorist coming out. Now, in a full sense, I don't think I was, I think I was having a game I wasn't certain of in American Esoterica.

Now I really understand how you can weaponize aesthetics. It's something I've thought about that leads us to talking about the Soros story. But the Soros story comes back for me in Ljubljana because it's... In Ljubljana I've been given this opportunity to make this headlining show where I'm effectively going to put together case studies of examples of artists whose practice has been weaponized as aesthetics to create disruption. I'm actually showing real, again, kind of like with Omul Negro, dangerous things, not just artworks, but things that are weaponized aesthetics. So for example, I'm the first and only person to show the... What the fuck is that movie called, The Innocence of Muslims, which is the film they declare, Hillary Clinton declared caused the burning of the Benghazi riots and the burning of the American Embassy. Was this movie that shows Mohammed in vile kind of situations.

So I showed that as an art film because I always saw that film as an art film. So I had different artifacts and things that represented magical thinking, the materialization of conspiracy theory as real conspiracies or in one... So there was one gallery that was very evidence and case study based, and then another gallery that was about the intersection of these things and accumulative power, maybe opening a door. I was trying to create a new language for the occult, not just, the languages of the occult are always retrospective, looking backwards at preexisting old, hidden things. Where's the new words that we can make that are occult and the new patterns that don't necessarily relate to the old patterns?

So I tried to create a gallery that was a ritual vortex kind of time traveler chamber or something. Yeah, the video that you've seen is what we could call the educational, the pedagogical video that a curator would do, except I've split my personality in two. I'm the daytime curator and nighttime curator and daytime curator is in a suit. He's very serious. He doesn't look at the camera. He's deadpan and nighttime curator is looking at the camera and he's fully a convicted, full of conviction and is the conspiracy theorist. It's this balance between these voices that are me trying to tell you about different ways in which this thing we're calling art is actually something else.

It's where I'm first forming this language where I'm really trying to consciously methodologically lose the word art, because calling it art is creating a placebo effect or a distraction to, for Trojan horsing. I believe that that's been the case for a long time, that art functions in that way. Of course it's a vehicle for ideology. But I think there's a lot of other ways when we can think of tactical media that we call a lot of tactical media art, and it makes it seem like safe, cute, conceptual interventions and social space. But no man, these are fuckin experiments, social experiments that are highly disruptive to perception and reality. Sometimes they're not done by artists, they're just packaged that way.

So this was a way to explore all these things and really address my problems that I had also with ideas of institutional critique, which in 2018, George Floyd's not dead yet. Institutional critique I never believed was anything more than a neoliberal form of lobbying. Now that is just totally obvious that institutional critique is just well-branded lobbying for very specific political purposes, propaganda for very specific political interests. It sounds so obvious to say these things now, but nobody was saying this shit back then. There's a lot of people that do hardcore institutional critique, but they would balk at the idea that they're a sock puppet, but they are, they often are. So anyways-

Leafbox:

Maybe that can connect us to the Soros Influencing Machine project that you're...

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah, dude sorry, I feel like I'm just giving you these monologues. I hate to-

Leafbox:

No, I think they're fantastic. I mean, I see the arc of your show, and it's interesting to see, because you're an insider. I'm looking at as a viewer, and I think it's pretty, especially the last three years, I think everyone's become aware of some of the psychological operations that governments and institutions partake in through media, right? What was so interesting about the Soros project is just so obvious. I think the whole conspiracy about Soros, I mean, there's layers to him, obviously, and I think you explore some of those in your PDF, but even most people think the deep conspiracy is that he's just an MI6 cover. You can't critique Soros for a variety of reasons. But behind that is just another government, either the British or the American. Like you said, they're trying to weaponize this media to influence culture and politics or the neoliberal aspect of it.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah. I want to address something that if we're looking at this arc, what have I done? I've constantly undermined myself and your ability, it's like a boy who cried wolf kind of thing. If you really are following the work, you always think, I'm playing a game. I'm constantly in the press called a trickster or a prankster. These names are so stupid because I'm a true believer and I actually have great intentions and I will... Everything I talk about and I'm interested in with spirituality is genuinely there. I'm trying to find cool ways to trick the mind to finding new alternatives. It's with absolute earnest that I do these things. But what I have, when you do these Hollis Benton, oh, how could you possibly... If I've done Hollis Benton, how could you possibly believe that the Soros thing is real and not just a conspiracy theory or me playing a game?

I think that's the great beautiful thing about it, is you are forced, of course, to ask that each time in a different way or with Trito Ursitori. It's hard to explain how much I've compromised my own character through social media and my voice and trying to make believe. So when it comes to the Soros thing, and this time that we're in, when everything is so conspiracy theory oriented, it's so easy to say that I'm just playing a game and stealing another conspiracy theory or something, when in fact, of course, that's not the case. This is legitimately real and legitimately a thing that we're protecting ourselves from seeing by calling it things like conspiracy theory or is even worse, antisemitic to look at and critique whatever the work of George Soros is. So if we look at this arc, it's this perfect case study into darkness, into real ideas of social engineering and weaponized aesthetics and things that I was touching on and playing with that all the while I've followed the story, I've learned so much from this story.

Like I told you in the beginning, I had a gallery. I represented artists that came from the nineties, from the Soros network. It's not a new story to me. I've been following it since I was a kid, basically. I've always turned it in my head like a prism. I've always renewed my thoughts about it. It was in Ljubljana when I'm doing my conspiracy theory show that I just was like, this is it, man. This is the real deal, this story, because it's got everything. Nobody talks about it. It's literally erased. No one's allowed to talk about it. It gets spooky as soon as you do.

It had so much taboo and occult en shrouding it that it was obvious that I had to fucken put a huge light on it and use it within my own work. But also, it's me going back to my roots as a journalist and my true interests, which have always been passionately engaged within the politics and cultures of Eastern Europe. I discovered this thing for myself when I was a journalist in 2006, and what, I've continued to do interviews with people for fuckin’ 17 years and always chased the story, but it was only in 2018 I was like, this is the real deal. This is the conspiracy that I've... This is the goonies narrative that I was just dying for and it's been chasing me this whole time. It was always there.

Leafbox:

So for people who aren't familiar with this project, could you give us a summary of the influencing machine and what the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, what they are, what this goonies world that you discovered? No, you were riffing in an amazing way. So it's great to ... I don't know if you've done this before, but you can clearly summarize kind of where you're going with your work. It's interesting.

Aaron Moulton:

Well, and I don't normally get to ... I appreciate this. I'm going to be honest, you're the seventh podcast I've done in the last six months, and I've really tried very hard to not be redundant, and I appreciate the ability to put this in a context of my whole practice. I'm really grateful that you're willing to look at this arc, and so it's great to be able to do this.

Leafbox:

Well, I think it's more interesting because everyone was just ... I listened to another one and they were just really focused on the Soros kind of Influencing Machine Project, but I was like, where is this coming from? I wanted to know where your arc actually is from. You just don't land at that kind of major project from nowhere.

Aaron Moulton:

Yeah, yeah, yeah. And so I'll just start with your question to introduce it. The Soros Influencing Machine exhibition that I did in 2022 in Warsaw at the Ujazdowski Castle is a full-scale anthropological study of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art Network, which is an unprecedented NGO, non-governmental organization, network of contemporary art institutions that pop up overnight in the recently collapsed Soviet Union all across Eastern Europe, every major city, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Tolin, Vilnius, Riga, Warsaw, Prague, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Almaty, Bucharest, Sophia, Kitchenel, Kiev, they all overnight with a span of three years suddenly have this asymmetrically, powerful new sheriff in town who is going to help shepherd creative practice into the new paradigm.

And when I was a journalist, when I ran Flash Art International, I had what I believed to be a very good awareness of the evolution of the global art world. This came from just my autistic curiosities of wanting to understand art in the art world and contemporary art and the flow of it. And having worked at Gagosian in different places, trying to ... Mapping and patterns is a big part of how I've approached all these flows of energy. And then suddenly I'm running a magazine after having done my curating degree at the Royal College of Art, which is at the time there were only 10 curating programs in the world, and the Royal College of Art one was one of the most prestigious, and its education is rooted in post-colonial theory and histories of curatorial practice.

So, you know, when you think about your education and mine, I felt I had a really in depth knowledge of the way in which the global art world appeared. And I at that time had been to many biennials and was going to as many as I could. And the biennial was such an amazing trait of the global art world. It's like this thing that everyone wanted a biennial and it was a way to embrace the global and create the global narrative within your regional environment. And so the biennial movement, which is kind of from ... Biennials exist prior to the nineties, but there's an uptick from 95 to 2005 that's extraordinary. And then around 2002, Frieze Art Fair starts. 2003 is the first Frieze Art Fair. And that represents what becomes the takeover of that global shift in how the speed and production and focus works, so it goes from everyone's going to biennials to now everyone's going to art fairs and the art fairs kind of take over as sites of production and visibility and practice. Biennials are still there, though, and biennials serve a different purpose. They're the nonprofit righteous art world, versus the commercial behemoth of whatever the art fairs were doing.

But in 2006, I'm running flash art and we're doing these regional surveys, focus issues. Every issue we do like a focus issue. And I'm seeing this reference to this network of ... I see this name, Soros Center for Contemporary Art. And I'm like, "Shit, man, I've never heard of that before." And I can't remember the first one I saw, but I googled it and then I saw there's another one and there's another one, there's another one. What the hell? You just kept finding them. And there was not enough for me to understand it, you know? There wasn't enough information out there to understand what it truly was. And I was just so curious. And at that same time, I had my burgeoning interest developing in Eastern Europe, which was a truly genuine, passionate, innocent, but highly enthusiastic interest of understanding art in a new way, in a new paradigm, in a place where there's no market, in a place where context is bricolage, and we can imagine it's a more kind of savage way to make things make sense outside of the confines of the properly institutionalized art worlds of the West.

And yet I'm seeing things in each of these eastern European art worlds that are just like new languages for me, but they look like the languages that I know. We do this stupid thing in the West of like, oh, you're the whatever. You're the Romanian David Hammons or something like that as a way to make sense of an artist's practice by making it make sense through a Western practice. You know? You would find things like that. There's an artist who's got a practice that's uncannily likes some kind of conceptual practice that you're super into, but it's operating on different terms, serving a different function, wholly different set of references and totally different effect. And I just thought, "Wow, this is wild." You know? Just getting into the art of these regions was so illuminating for me because I just saw the role of the artist differently, their relationship to society, what their work does.

And avant garde is a military term in its truest sense, and the truest form of avant garde is survival. And that is what most avant gardes of Eastern Europe are consisting of is artists making practices that are about surviving in these conditions and against systems, previously quite oppressive systems. And I was in, you know? The more I looked, the more I was in. And this Soros thing was like this great detail that was like a through-line that I didn't understand, but I wanted to. And so I created a research trip for myself and in August 2006, I traveled to 10 cities that had Soros centers. And to tell you that story, they said the Soros Centers, they popped up from starting in ... The first one is in Budapest and it's in '89 that it ... The Soros Fine Art and Documentation Archive begins '88, '89, and then it changes its name in 1991 to the Soros Center for Contemporary Art Budapest. And then in '92, Prague, Bratislava, Warsaw and one other open up. '93, it's Kiev and ba, ba, ba, ba, ba. Each year there's like four or five. And then in '96 it's Saint Petersburg, Odessa, Kitchenel. And then in '98, Almaty in Kazakhstan is the last one that opens.

By the time Almaty opens, these things are already ... The majority of them, there's 20 of them total, they're already in what's called the sunset years, where George Soros has taken this project where he's manifested this enormous and unprecedented network of art centers. And he's already starting to cut the funding on them. They're already disappearing. They're shadows of how they began. And they began in this incredibly bombastic and very asymmetrically powerful and influential way, and then they're already out the door by the year 2000. You know, half of them are gone and half of them are transitioning into becoming ICAs, or ICA or the Latvian Center for Contemporary Art Riga. They're dropping the Soros name to become independent art institutions.

Leafbox:

Can I ask a question about context. He just decides to open all these 20 gallery centers overnight basically. Are they commercial galleries? Are they just nonprofits? I mean, you have some quotes about he broke down the USSR. I'm just curious, what do you think his intention is? Did you ask or what was your journalistic practice in investigating the start of this project?

Aaron Moulton:

I can tell you historically he has never said what these things were and why he was doing them. He's never said what his interests were in art. That is kind of left up to ... There's this pioneering leader of these things named Suzy Meszoly who was the architect of the network. And he just had full faith in Suzy to do Suzy's vision. And what were they? They are a subsidiary of the Open Society Institute, which is the largest and most powerful NGO network on planet Earth. Open Society Institute, which is referred to as the Open Society Foundation. The Open Society Institute is George Soros' think tank NGO, but it's more than an NGO. I think calling it an NGO really simplifies the breadth and intentions of this thing. This is literally the machine that is going to manufacture all the details of transition and in terms of shepherding each of these vulnerable places into the new world, into the new world order of becoming a part of the European Union, becoming Western, pro-Western.

So the Open Society is involved in any number of radical changes that Naomi Klein refers to as shock therapy in the grand scheme of how all these economies and cultural structures were being reconfigured and socially engineered to become pro-Western. And the Open Society Institute is involved in everything from healthcare, political science, education, et cetera, et cetera. And it's vast. And the Soros Center for Contemporary Art Network is like a short-lived experiment within it. And they are art centers that are non collecting, like modeled after the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston or London. And they are not just galleries, though; they're archives that are going to collect the lost histories of the sixties and seventies and eighties under communism to help create a new history, a new art history of radical art practices that were happening underneath the Iron Curtain, behind the Iron Curtain, in a way establishing a narrative that there's this burgeoning individualism, this autonomous creative voice that's trying to break through the oppressive structures of socialist realism and so forth.