Interview: Eric Shahan - Shinobu Books

Diving Deep into Japan's Hidden Treasures: Martial Arts, Ninjutsu, Esoterica, the Enigmatic World of Japanese Tattoos and more with Translator Eric Shannon

Eric Shahan, an American translator based in Japan for the last 20 years, has been independently publishing translations of Japanese texts, many of which are esoteric or obscure with a current focus on martial arts manuals, the esoteric, irezumi or tattoo culture, 18th century manga and other works.

In this conversation we discuss his approach to translation, his wide range of interests and his encouragement and tips for others try independent translation research and publishing. Shahan's translations are available on Amazon.

Twitter: @ShinobuBooks

Instagram: @Shinobu Books

Leafbox:

Eric, I wanted to thank you first for responding so quickly on Twitter. I got kind of mesmerized by your books. I was at the Okinawa Festival here in Honolulu, and I came across a group of, I think two or three tattoo artists, females who themselves were Okinawa descent and they had copies of your book. And I met the maybe N three level Japanese, and I've just never heard of this topic. I mean, I have some tattoos personally. I have stick and poke tattoos and I'm somewhat familiar with tattoo culture in Japan, but this was just mind blowing and something that was just never exposed to me. Both Okinawa is kind of a isolated place in Japan I've never been, and I just wanted to thank you for exposing these women were really excited about your work.

They gave me, I looked at both editions of your book and they were restarting and trying to renew this kind of lost art. And then I spent some time looking on the internet and I was like, who is this guy? Where did you find this topic? What interested you? I assumed you were an anthropologist or some type of researcher, and then I found that you're a translator. And I was like, well, I got an interview. You had a lot of other topics interested in martial arts translation, Japanese language study, some of the cult. I looked at your Twitter feed and you have a lot of great topics on there as well. So I don't even know where you are in Japan. Eric, why don't we just start there and then maybe we can just learn about what brought you to Japan and how you've been approaching, I guess, everything you're working on.

Eric Shahan:

Well, that's a really nice anecdote you just told me about those ladies in Hawaii that have copies of my books. I'm really quite flattered by that, especially considering they are from Okinawa and are also interested in tattooing, so that that's really quite flattering to know that the work I translated is helping people out. And basically I got into, I'm in Japan. I've been living in Japan for 20 years and I live in a place called Chiba Prefecture, which is just east of Tokyo and kind of out on the east coast of Japan. And I've been here for about 20 years and I didn't know any Japanese when I came to Japan other than the standard Japanese that every American knows, like Samurai Ninja, Kamikaze, Harikiri, and stuff like that. As soon as I got to Japan, I really got into learning Japanese and basically through self-study, gradually developed, got through Hiragana Katana into kanji, into regular Japanese newspaper level Japanese, and then I started poking around at the pre-war Japanese stuff, which is, if you're familiar with it, it becomes one level more difficult.

And so after working on that for a little bit, I started being able to edge back even further in time into the Meiji era and then even the Edo era to a degree. So right now my focus is just translating stuff that I enjoy. I don't have, I have almost no contracts with anybody. I do occasionally take freelance work, but most of it is just stuff that I've discover and I'm interested in it. I'm like, I'm going to translate this book and I translate it and publish it, and I independently publish all my stuff through Amazon and I just keep chugging away at stuff I find interesting.

Leafbox:

And then where are you from, Eric originally?

Eric Shahan:

I'm from the United States, east coast. I was lived in Texas and then later on Virginia.

Leafbox:

And then what brought you to Japan? Originally?

Eric Shahan:

Just I was looking for a change of looking to mix up what I was doing. So I applied to an English conversation school through a newspaper ad in the Onion when I was visiting Chicago one time. And I responded to an ad and got recruited. And at the time, if you got accepted for the interview, they set you up with everything you needed to get started in Japan. You got a job, a work visa, and they sub rented an apartment for you. So when you have that three point set all ready to go, it's easy to start your life in Japan.

Leafbox:

And then did you study anything related to language learning or language translation or anything like that? Formally? No.

Eric Shahan:

No, nothing like that at all. I mean, I studied German when I was in college and I was always interested in Japanese anime and Japanese manga. Originally, there were very few movies available in English stuff like Akira and Fist of the North Star and RoboTech and our CROs and machine, what's it called, trans or Z and stuff like that, these old anime. I really liked those. And then finally, eventually Dark Horse Comics started publishing Lone Wolf and Cub in English. I was really, really fascinated with those. But when I came to Japan, I didn't have any, it was not my intent to become a translator or anything like that, but I enjoyed translating Japanese and I also started doing martial arts for the first time while I was in Japan. And while I was doing martial arts, the organization I was in was called the GenCon, and it has several branches in other countries, and those members from other countries would come to Japan to train directly with the sensei.

And after a while, it got to the point where I was able to translate questions and answers that these people that were much more skilled than I was had. So I was translating back and forth these questions and stuff like that, and eventually they started asking me if I could translate some items from Japanese into English related to martial arts and related to ninjitsu and stuff like that. So it was like, yeah, I'll give it a try. And so slowly I kind of got into translating just first of all, just by helping people out with questions and answers and short articles and stuff from a hundred years ago and stuff about martial arts or Ninjitsu or something like that.

Leafbox:

And then what was your language? I mean, why don't, just before we go to your language development, I'm just curious what brought you to Okinawa tattoo culture and where you even discovered that? And we can go back to the original place.

Eric Shahan:

Let's see here. So you kind of have to back up a little bit before that because I was very fortunate that around the time I started being able to read and write Japanese as well as speak it, I realized that the National Diet Library in Tokyo had digitized a bunch of their collection and made it searchable. So you could type in stuff like jujitsu and all the books with jujitsu in the title and to a degree in the contents would appear because that stuff is in the public domain. It was free for use originally, my first book on tattooing was called Tattoos as Punishment, which looked at the punishment tattoos in the Edo era while I was tattooing the, while I was researching the punishment tattoos in the Eddo era, I also at the same time came across, I knew tattooing and tattooing in UQ or the Okinawa Islands. So from my original book, I just had a little bit of an intro on the, or a short section on, I knew tattooing and a short section on Okinawa and tattooing. But after I finished that book, I really wanted to expand on both the I knew and the Okinawan tattooing. So these books I just released about tattooing in Okinawa, the two volumes are basically expanding on that first section, I translated, I guess it was five or six years ago.

Leafbox:

Just to summarize, what's the tattoo culture and during the Eddo period, what is the punishment regarding, so during Daimyo Era or what was the tattoos about? Is that for criminals like markings? What did they serve? Correct.

Eric Shahan:

During the Eddo period, which was basically started in 1600, there were criminals that were convicted of stealing, or actually one common crime was dining and dashing, which sounds kind of really modern, but they would go to a hotel or a brothel order, a bunch of food and drinks and some entertainment and then try to run out on the bill. And so such people would, when they were caught, in addition to being thrown in jail for a month and then giving a severe beating with a bamboo cane, it would also be tattooed on one or both arms with a black band about two inches thick going all the way around the arm. And that would be an indelible mark that you couldn't conceal, really. So everyone would know that this person's a criminal and could not be trusted. And in the Eddo period, each region of Japan, each domain of Japan had its own tattoo to design. So some places had a bar, kind of like a band going all the way around the arm. Some places had one kata letter, for example, Sado Island that's kind of in the sea of Japan would just have a kata tattooed on the arm. And other places had, well, just various designs. And then there were some that even tattooed directly on the forehead, the famous one being the tattoo of a dog or the tattoo of the kanji dog, which was actually done in stages in four stages

Leafbox:

Based every time. Got it. Every time you did a crime, they would add a character stroke.

Eric Shahan:

Correct. And they also had the symbol of the Buddha tattooed on the forehead or even the kanji bad watery. So I thought that was really interesting. So the tattoos is Punishment book that I did. It basically focused on those tattoos and what the tattoos were in each area and what they meant. And then as well as some case studies of what kind of people, why was a person given a tattoo. And like I said, if they stole a bundle of some swords and kimonos, they would get a tattoo or something like that. If they stole more than 10 pieces of gold worth, then they would usually just get their head cut off so they wouldn't get tattooed.

Leafbox:

And then how did you even find this one topic of interest? Do you have tattoos or interested in tattoo culture, or what was the attraction?

Eric Shahan:

I had heard that everyone knows the Yakuza, they're tattooed and they cut their fingers off and stuff like that. And I had heard that the punishment tattoos, the, what is it? So the criminals in the Eddo era got tattooed on their arm, and I had heard that the Yakuza just sort of expanded on that kind of like, yeah, I'm tattooed. And they just sort of took the punishment tattoos and just expanded them into dragons and stuff like that. So kind of owning the fact that they were tattooed, in other words, is what I had heard for a long time. But when I looked into it, it sort of actually had no real connection. As it turns out, tattoos became very fashionable beginning very early in the Edo period around the 1650s. Young lovers would tattoo each other as a sign of love. We both have a tattoo of the initials of the other person. And then those tattoos began growing more complex through time.

Leafbox:

And what was the tattoo artist culture? I mean that they just specialized or the people doing the punishment tattoos, were they just like the police informers, the Samurai class?

Eric Shahan:

No, they were the Hanin in the prison. They were the Hanin. They were non-human cast because they had been completely, there were outcasts from society in prison. So Samurai wouldn't be, samurai directed it, but he didn't actually do the tattooing.

Leafbox:

Got it.

Eric Shahan:

It was a bundle.

Leafbox:

Is that below the men type cast, or even,

Eric Shahan:

That's a good question because it's kind of difficult to say how exactly they're arranged. But there was the Burakumin and then there's the Henin, and then there's the Etta. So they're all kind of unclean, outcast kind of people, but the

Leafbox:

Based on their occupation, basically. Right. And being criminal, for example,

Eric Shahan:

When the Henan in prison, they had been convicted of a crime, so their status had been removed completely. Got it. So that's them. And then the Eta were like people that did unclean jobs, like you said, but it also included people that were just sort of in criminally insane or drunkards or something like that.

Leafbox:

I mean, jumping to the modern day, when did the taboo start? Did they then branch off of the kind of Romeo and Juliet tattoo culture, or where did they pick that up?

Eric Shahan:

There was some element of tattooing as a means to intimidate people. So like I said, early on, there were tattoos between lovers and especially Courtesans in the red light district. And their best customers, they would tattoo themselves to show their devotion. They also did stuff like cut their pinky fingers off the courtesans. So that was another way to show their devotion later. And then those tattoos at that time were all self applied just with a straight razor and a little bit of a calligraphy ink rubbed in. So the professional tattooist did not emerge for some time. So originally it was just all done by hand or done by self applied or by another person doing it to you who was not a tattoo artist, just someone who's giving it a go. So that sort of progressed for a while. And then in the late 16 hundreds, you started getting people tattooing designs meant to intimidate like a skull or a severed head nama, like a head that's been cut off. And these would be used to, you just show someone this tattoo and they would get scared and give you all their money kind of thing.

Leafbox:

Wild and then contemporary, where do you think the contemporary feeling of tattoos? I mean, I have some tattoos. They're so small, and I mean, ofuros always make it, you can't go and you have to go to the sento. I mean, in sento culture, they don't really care at all, but that's a subclass. I'm just curious, what are the current associations and when did that come post-war or where did those current feelings of tattoo, are they still linked to this tattoo as punishment or fear of the tattoo?

Eric Shahan:

Well there was also, eventually, like I said, these were running concurrently. So you had people that were showing tattooing themselves as a sign of devotion at the same time that they were tattooing people as punishment. So you have to remember those were both happening at the same time. So it's a little bit muddled what exactly was going on. And then when you get to the 17 hundreds, tattooing had gradually been increasing. And so by the, I guess it was towards the mid 17 hundreds, a lot of the outside people that worked outside naked, so to speak, wearing, like the steeple jacks and the bearers, they all started getting these full body tattoo suits. And it was to the point where you couldn't find a driver without a full body suit of tattoos. And even like the steeple jacks, the guys that did the roof raising in buildings, if you wanted to join that guild, you basically had to have a tattoo, otherwise you weren't going to get in.

So it was a really, really big culture. And the Eda era tried several times to outlaw tattooing, and they passed laws. You're not allowed to get a tattoo, you're not allowed to tattoo people, all that kind of stuff. But they just got ignored. So it just kept building and building and building. And so it was always illegal to tattoo. And even in the Meiji era, it was still illegal to tattoo people or have a tattoo. And at one point, they even had to issue special permits for people that said, oh, I got a tattoo because tattooing was illegal, but you have a tattoo, how you prove you got the tattoo before the law and not after the law. So they started issuing these permits saying, I'm permitted to have a tattoo because I got it before the law was enacted. So the government was trying all kinds of things to get rid of this culture, but it just wasn't really happening. Sorry, what was that question again?

Leafbox:

No, I was just curious. The contemporary Ofuro bath.

Eric Shahan:

Oh, in the baths, yeah. Yeah.

Leafbox:

I'm curious, what's the linkage there? Obviously to the criminal, they associated with criminal elements still, or fear? It's all the same reasons, I guess.

Eric Shahan:

Well, in the sixties, in the fifties and sixties, there were a lot of Yakuza movies out that showed the Yakuza, these bad guys with tattoos. And so that really embedded the image of the tattoo as something associated with not a nice person. So

Leafbox:

Then jumping back Okinawa into the Ryukyu Islands, I mean, well, why don't you walk me through where you found them and how they differ are similar to the other mainland Honshu Japanese culture.

Eric Shahan:

In one of the papers, in the first tattooing in Okinawa book, which was published in 1893, this guy named Miyajima just decided to go to both the VQ Islands and up to Hokkaido and look at the tattooing that was done. And he was trying to see is, is there any connection? Why? Because in both places, they have tattooing in both places, it's primarily the women that get tattooed. And so his question was, is there any connection at all, which is a great question for 1893. And he found that the designs were completely different, the reasons were completely different, and there didn't really seem to be any connection. And if it was lost centuries ago,

Leafbox:

And was he an anthropologist or he's just an interested person?

Eric Shahan:

I couldn't really find out much information. I think he was a lecturer, maybe a university lecturer.

Leafbox:

And so how did the two cultures differentiate themselves through Ryukyu and Ainu tattooing?

Eric Shahan:

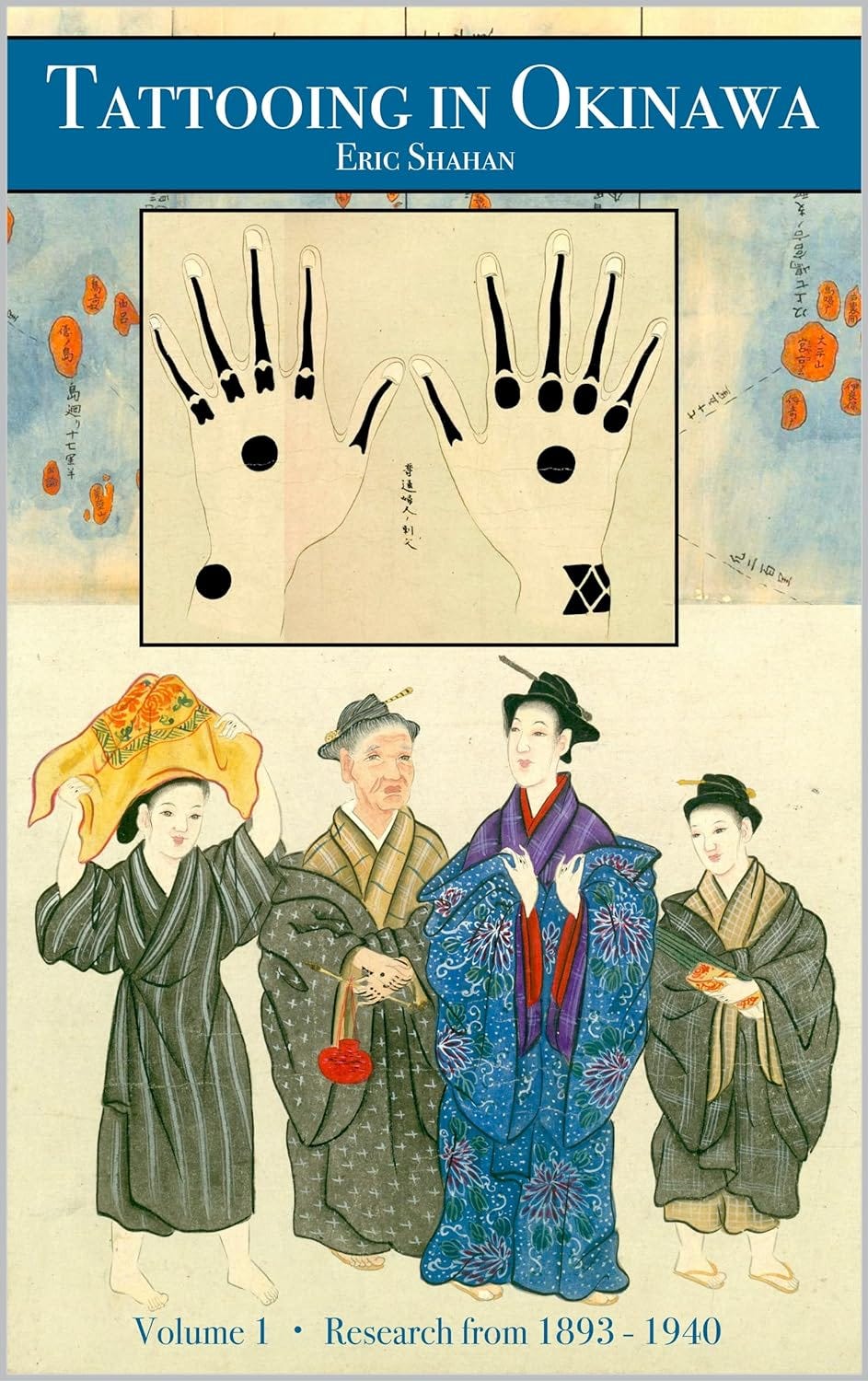

Well, the Ainu tattooing is kind a big question mark because they didn't have any written records. So the only information we have comes from what was collected by explorers or researchers in the Edo era, and especially in the Meiji era. So it's not really clear where those tattoos originated as far as the Aino. The Ryukyu Islands first came in contact with the, Ainu first started getting mentions in a Chinese explorers books. And in the 1300s, the Ryukyu Islands made a contract with the Chinese mainland to become a tributary. So they started, basically, it was a trade agreement between the two countries. And as that trade agreement progressed, people from China would travel to the islands of Okinawa and for trade, and they would report on what they saw. So starting in, I think it's like maybe 14, 1390s or something like that, these trade missions, the guy that was sent out would record what he saw in Okinawa, and he recorded women that having tattoos on their hands.

And so that was the first mention of tattooing in the Okinawa islands. And interestingly, there's several of these books, well, there's many of these books detailing what happened on these trade missions. And they have little snippets here and there of what happened regarding tattooing. And so the first guy mentions that the tattoos were of insects and tigers, and then the next guy who's 80 or a hundred years later is the previous guy mentioned, the tattoos look like insects and tigers, but they actually don't look like that at all. They look like water, flowers or other kinds of plants. And then the guy after him in the 1500 says, yes, no, there were no tattoos of insects. Yes, all the women have tattoos and they walk around barefoot and they all have to. Yeah, and it's an unusual site. So the first descriptions of tattooing in the Okinawan Islands are from these Chinese kind of travel log reports of the ambassadors from China visiting the Ryukyu islands. The first Japanese description of tattooing in Ryukuu Islands comes in the early 16 hundreds. Monk, a priest, a monk of the 10 sect of Buddhism, traveled to the Ryukuu islands as a missionary. And he recorded that the women all had tattoos. And he speculated, he was wondering, was this the same, what do you call it, as he noted that they don't blacken their teeth like they did in Japan, you know what I mean? Back in the Ian era, the courtly women would dye their teeth black.

Leafbox:

I didn't know about that. I think I've heard of that originally. And what was the reasoning for that? They thought it was beautiful or,

Eric Shahan:

Yeah, yeah, thought it was beautiful. So the women in the, what do you call it, the imperial court would blacken their teeth, and that was just, it was called Ohaguro, and they would blacken their teeth with some kind of kind of paint or something. And this priest who goes to the Ryukuu islands, he's like, well, they don't blacken their teeth, but they do tattoo their hands. So I don't know if there's some connection with the use of black. And that's really all he says in this up the 16 hundreds.

Leafbox:

And then what was the, I think one of the tattoo artists was saying that they used it as markers for where their island, which island in Ryukyu kingdom they were from, and then markers of life events, puberty or pregnancy or marriage. Right.

Eric Shahan:

This is another aspect. It's not clear. There's hints of it. And all the sources I've translated so far give slightly different reasons or slightly different information regarding the tattoos. So the tattoos were certainly different on each different islands, but there were some, what do you call it, some similarities. For example, for the most part it was limited up. The tattoos only went up to the wrist bone, and they were all done on girls, they were all done. They starting fairly young and generally extended up until the woman was married, though there were some tattoos also given when a woman reached 60 years of age, which is 60 years is a significant, it's called krei. You've gone through the, you've gone the, what do you call it, the zodiac signs. You've gone through all the zodiac signs five times until you come back to your original birth sign. So you would get tattooed again then

Leafbox:

Wild. So there's a Chinese influence there with the lunar calendar as well, and all kinds of markers. Is it true, one of the tattoo artists was saying that they used it as an anti piracy slash kidnapping because women would be, supposedly, they were beautiful dirt from the Ryukyu islands and the Chinese would kidnap Okinawa and women and the tattoos served as some type of home beacon?

Eric Shahan:

Well, there was definitely, you could definitely, you mentioned before, I didn't address that, but you could tell where a woman was from based on her tattoos. So was that a kind of mark of pride, or was it a way to keep track the people on an island? So there's a little bit of a question mark about that. Also, there were some differences in class with the tattoos. For example, on the main island of Okinawa, the tattoos were fairly standard throughout the island. There was sort of the bamboo leaf design across the back of all four fingers, all five fingers, and then a small ovals on the knuckles. However, if you were kind of a woman from the upper class, the lines would very thin. And as your class was, I don't know, lower, so basically a farmer, an upperclass woman, would have a very thin kind of pencil thin line, whereas if you were a farming girl, you would have a really thick line that was almost like you took a big black magic marker and covered the entire back of the finger. So it was all black.

Leafbox:

What were some of the challenges finding, I mean, the Okinawa language is different. So what was your research process like and did

Eric Shahan:

Some of the sources, they write the Ryukyu language in Katana, right? So it's like a song about tattooing, and it's all written in uq, so I can't really make heads or tails of that. But they give a Japanese translation of what the Ryukyu language says, so I can translate that into English, but it's getting a little bit far from the source material at that point. Unfortunately, the way they spell words, it doesn't really match the words that are in common Ryukyu dictionaries. So I try to search some of these words and just nothing comes up. So just the way that Japanese person transcribed the Okinawa language into Katana or it's the dialect, but it was hard to really confirm any of what some of these people wrote. So I just left it as is, this is what this guy wrote, this is what he says it is. Nothing really.

Leafbox:

Did you have any contact with researchers in Okinawa or any linguistics or just other researchers interested in this topic, or are you, I mean, it seems like you're the only one in English really doing this kind of work.

Eric Shahan:

I think there's, there's not a lot in English. There's definitely people doing research into old traditional styles of Japanese or Okinawan tattooing. And there are some, basically, I'm friends with people on Instagram that are doing these type of tattooing on currently Okinawan style, tattooing up the back of the fingers, tattooing on the wrist bone and stuff like that in traditional Oko and style. So I'm friends with them, but a lot of times, even if they're Japanese, they're working from basically the same sources I'm working from just they're using the Japanese version.

Leafbox:

Got it. No, it is just a very interesting, strange game of telephone because a lot of the people, you're a foreigner reintroducing mean some of the women found your work, and they almost were, they were tattooed in Western style, but their Japanese descent, and it almost became kind of like a cultural homecoming for them to discover that Okinawa had some of this tattoo culture. So that was really interesting for me.

Eric Shahan:

I'm quite flattered to hear that. I appreciate letting me know about that. But this is exactly what I try to do is just make available, there's wonderful sources in Japanese about all kinds of topics. So I'm trying to just translate the stuff that's put out, stuff that can be interesting and useful for people. And

Leafbox:

Did you travel to the Okinawa islands at all for anything or to find texts in their research libraries or anything like that?

Eric Shahan:

For now, I've actually just basically exhausted all the research papers that were online in the first book. I had some from 18 93, 1900 and the 1920s and thirties, I feel like there's more out there, but one issue is, I don't know what they're called. They sometimes don't necessarily say tattooing. It's just like the culture of the culture of Miyako Island or something like that. So it's a big book that'll have all about Miyako Island and maybe a little bit about tattooing, but you kind of have to go through the whole book to find the section you need. So I definitely think there's more resources out there, and I'd like to go to the Okinawa Islands and do some more research. I have not been there yet, though. I have been to several islands that are associated with Tokyo. They're straight down out of Tokyo, like Oshima big islands and Niijima New Islands. But I haven't been to Okinawa yet.

Leafbox:

Wild. And then what other topics are you, I mean, maybe we can jump from tattooing onto, I mean some of the martial arts or what are you finding the most interesting right now in translation or how are you approaching, you said there's so much interesting topics. I'm just curious what your focus is in right now.

Eric Shahan:

Well, my focus is I'm trying to focus, so I've been doing a lot of jiujitsu stuff, and especially how jujitsu was presented in the early Meiji era, because up until in the Edo era, martial artists were basically sponsored by the government to train, because originally each domain had its own army. Each managed Japan has own army, and then its own army instructor, military martial arts instructor. And so after the major restoration, those people all lost their jobs. And so some of them tried to open up private dojos and start publishing material about how to train in martial arts. So I started translating those early jujitsu and Ken Jitsu were sword fighting manuals that were published in the 1880s and 1890s up until the 1920s. And at the same time, there was also a big boom in judo and jujitsu in America and Europe, and this is because Japan defeated the Russian fleet, sunk the Russian fleet in sign of Japanese war.

So that was a big shock to the western world because that was the first time an Asian country had defeated a Western power. Up until then, you had the unilateral trade agreements, or what do you call it, unbalanced trade agreements with China and stuff where the Western powers had basically extra territoriality where they had the ability to, they were not subject to local laws in any way, shape or form. And so basically they just ran roughshod over the country that they were ostensibly trading partners with. But after this, it was kind of a wake up call. So a lot of Western people were like, excuse me. They were like, how is it that Japan was able to destroy a western fleet? And they looked at Japanese culture and they saw that everyone did judo and jujitsu. So were like, oh, well that must be the reason.

So let's look into this. So there was a big boom in judo and jujitsu in the United States. And recently I've published a guy named Maeda Mitsuyo, a judo practitioner who is a direct student of Kano Jigaro, traveled to Europe to try to help expand judo in Europe and also in America. And he wrote a biography, an autobiography of his travels, and all the duals he fought in the 19 hundreds through, I'm up to 1908 now. Is he the one who went to Brazil to then? Yes, that's him. That's him. So I'm working through his, it's, he wrote an autobiography, but his editor or whoever wrote sort of made it novelize it, I guess, because he discusses it's told from the third person, like, Maeda did this and Maeda did that. So he kept a journal of all his bouts, sent it back, and then the guy kind of made a biography of his travel.

Leafbox:

It's funny, both of these topics, the Jiujitsu and tattooing, I'm just curious how you can tie in the Meiji era and the modernization and how they, I mean, the Okinawa culture got subdued during that period, and then the Jujitsu culture got subdued as well.

Eric Shahan:

Well, jujitsu still had a life as Army and police training, and a lot of schools were vying to get those contracts, get a contract with the police or the military to teach, because that was basically a way to regain their, what do you call it, find a means to continue their training, life, teaching and training, and continue their school. So the schools would all we're looking to do that. So there was fierce competition amongst the schools to get those contracts. And you also had judo at the same time, made by Jiro, and he eventually was able to get Judo installed as the official martial arts, not only in school, but also in the police force.

Leafbox:

But wasn't the Judo kind of the American occupation force kind of banning the jiujitsu, or is that a misunderstanding?

Eric Shahan:

Judo was, I believe Judo was allowed to continue uninterrupted. I'm not entirely sure about that, but Ken Jitsu, the sword fighting was Kendo was the one

Leafbox:

That was, oh, Kendo was softened, right?

Eric Shahan:

So that one, they were like, it's connected directly to militarism and the previous government, so we're going to ban that. But with a lot of hard work and working hard to convince the American general headquarters, they finally were able to prove that kendo is kind of a, it's not a killing art. It's a way to develop the athletic spirit, not just teaching how to kill kind of thing. It briefly was called, was it Shinai Kyogi, Like shinai, are the bamboo swords wrapped in leather that they used to use in trading martial arts, so that you were allowed to use it was briefly called that before it actually became Kendo again.

Leafbox:

And then Eric, I'm curious, just stepping up a little bit, what's your approach to translation then? How are you dealing with these texts? What's your process? Maybe you can talk about your language learning development, and that's

Eric Shahan:

Well, as far as learning didn't go, I taught myself, I taught myself Japanese by living in Japan, and as far as reading, I started off with a book called a Graded Japanese Reader. That was a really, really old fashioned book, but it really helped me out a lot. And from that, I graduated to the Asahi Kids newspaper, which was, it's called Kodomo Shinbun, and it's got short articles, but it's real news that's timely, and I subscribed to it. So it came to my house every day, and I would read these short articles that had all hiragana on it for about six months, and then I switched to the regular Aashi newspaper and was able to begin to read for real. That was how I learned to read and basically write, because I would just copy down the articles As far as getting into translation goes, basically it happened at the same time, because as I was studying those articles, I would write down the keywords I didn't know, and then basically be after reading an article eight or 10 times, you basically know it by heart and sort of became the defective way I translated things.

Leafbox:

Do you have any advice to, I don't know, language learners or just curious if you have any tips for people learning? I mean, Japanese is probably one of the hardest languages,

Eric Shahan:

Other than it absolutely is tough, and you can definitely learn to read on your own using that text. I mentioned in that system I mentioned just to go from find a graded reader, and I'll send you a link to the book I was mentioning, so you can definitely learn to read through there. And then there's also very easy manga to read Doraemon and stuff like that. That's a good way to start actually being able to read stories and stuff like that. I would advise against trying to read children's books. Books are not as easy as you think, and it was really surprising because they used old fashioned expressions and stuff like that.

Leafbox:

No, there's a lot of slang. My daughter takes Japanese, and some of her books are just so difficult to read because they use all kinds of obscure sounds sometimes

Eric Shahan:

And right, and those are funny for kids of if you're a native speaker, but if you're trying to look it up, it's like, what is this word? And it's just like, I remember it was like the Oji "so sa na" , and I'm like, what the heck is So sa na? And it's not a word. It's just like something an old person would say. So I bought this hard bound Momotaro book, peach Boy.

I was trying to go through it, and it was just like agony. What does this mean? What does this mean? I couldn't figure anything out because it was a really old timey story. So there's all these old timey words and old timey expressions, which is fun for kids to hear their parents read to them, but it's like agony, trying to figure it out. If you're from the perspective of a foreigner, plus, it's all in hiragana, so you can't even figure out where one word ends and the other word begins. It's making you, it was really tough.

Leafbox:

And then when did you just start deciding to start publishing these books you thought should be promoted in the West or abroad?

Eric Shahan:

That's a good question. I didn't really decide. Like I said, I had some people ask me, there was a book called Ninjitsu, the Essence of Ninjitsu that was published in 1917 that a lot of people really wanted to read because very famous it, it's kind of the source of a lot of fundamental knowledge of ninjitsu because it mentions all kinds of things like Ninja wearing a mask over their face and dressed all in black and using their sword to climb over walls and stuff like that. So everyone was asking me about to translate this book, and I was like, all right, I'll try it out. So this book was really tough to translate. It was written in the show, why Era, but I kept at it and chipping away, chipping away, and eventually I was able to finish it and publish it after about two and a half years. Fortunately, this book is extremely old. It's a hundred years old Japanese, and I wouldn't have been able to translate it if it wasn't for the online. It had been digitized and published online. So that's really, and then also at the same time, there was also self-publishing became available because up until now, if you wanted to self-publish a book, you had to go to a publisher, get 500 copies printed, and then

Leafbox:

Sell them.

Eric Shahan:

Yeah, go run to bookstores in the cities around your town. I got to drive up to Richmond and then down to Norfolk and then up to DC and stuff like that. Whereas Print on Demands meant there was no upfront money. And also I didn't have to go to the post office and mail write, post office labels and stuff like that, which is agony.

Leafbox:

How has the business been of self-publishing these books? What's been popular? What's been a failure? What do you getting more demands for? I'm just curious on that side.

Eric Shahan:

Let's see. What's not popular is I started translating this series of Edo Manga, so it's manga published in the 1700s. And these stories are hilarious, man. There's one about tattooing, there's one story about a bunch of guys that get tattoos, and the tattoos are so realistic that they come to life and start going off and having adventures on their own. So there's like two severed heads that go running around trying to find part-time jobs. And there's another one where a monster goes rampaging around trying to find his adversary. So it's a really funny stories, and they're not selling well, but that whole series of stories from the 1700s is fascinating. So I'm continuing to publish them, even though they're not particularly popular as far as popular stuff. One, a book called ok.., what's it called? Okinawan Kempo by a guy named Motobi Choki who's a famous karate practitioner.

And when I decided to translate that book, I had previously translated an interesting book on also called Kempo. Kempo is basically like jujitsu, but I translated a book on Kempo, and I was like, oh, this book was interesting. I wonder if there's any more books on this Kempo jujitsu that was currently being used by the police in Japan. The first book on Kempo was from the 1880s, and I found this book by Buchoki, which I think was published in the twenties, or maybe it was in the thirties, and I published it and it sold really well, and I didn't understand why. And the reason was is because there's an entire organization that still exists of bu choki karate schools all over the world. And I was like, oh, this guy's famous. I didn't know that guy was famous, because all the other books I'd published up to that point had been, no one said had ever heard of any of these people. So I sort of accidentally translated a book that was by a person that was quite well known, and the book became very popular. So it's kind of a funny story. I was like, oh, sorry, I didn't realize that there was a whole organization devoted to this guy's teachings.

Leafbox:

Did they end up contacting you or,

Eric Shahan:

Well, I didn't understand why. I was like, why is this book really popular? I didn't really, I actually don't do any promotion or anything really. I just publish the books and then I would write on my Facebook page or on Instagram, oh, finish another book. That's it. That's, that's the extent of my public relations. I mean, in the last couple of years I've done a couple of interviews, but for the most part it's just been word of mouth as far as I know.

Leafbox:

So

Eric Shahan:

That's why I was surprised when you told me about the Okinawa Festival in Hawaii. There was people with my book. I was like, wow, that's quite flattering.

Leafbox:

Yeah, I'm just curious. Yeah, I mean, a lot of your topics seem esoterica, I guess, niche, so I guess you're going for the long tail. Have any publishers contacted you, like Viz Media or anything? I mean Oh, no,

Eric Shahan:

No, no. I tried to get in contact with some publishers, but didn't really get any answers, so I just continued to publish what I like, and there's a little bit of a chain reaction kind of flow with my work. For example, those Jiujitsu books mentioned some of the esoteric aspects of martial arts, like Ji the Nine Seals where you fold your hand in different shapes in order to, as a way to bring peace of mind and offer a kind of mental self-protection. Those were mentioned in the Jiujitsu books as just an aside. So I took that aside and then did more research into it, and that's how I got into the esoteric books, or there'd be a word or something, or a phrase mentioned in a book about traveling in Japan. And I found a book, and I use that to translate a travel book about Edo Era Japan where a guy gives basically travel advice in the year 1800, how to prepare your stuff, how to put your sandals on, how to keep yourself safe in a hotel room while you're traveling. So there's a little bit of a chain reaction as to what I'm translating. So I guess that would be my advice to anyone who wants to get into translating. You can take a look at, if you're doing Japanese or even any language, really take a look at your national archive, find a book that you think would be interesting for you, and then translate it and self-publish it, because I think you'll find an audience at some point.

Leafbox:

What are some of the most interesting rabbit holes? You've gone down, I've never heard of this kg issue, or I'm just curious, any interesting discoveries? You're like, wow, this is really weird or interesting, or what did you find?

Eric Shahan:

Well, whole, I titled that one book Tattoos as Punishment, and I didn't, because I thought there was a connection between punishment, tattoos and the Yakuza and the popularity of tattooing, and that connected to the modern day tattooing. And while that was completely wrong, I did find all these interesting avenues. I found all sorts of wonderful books about the i u color illustrations, talking about their lifestyle and stuff like that. And I've started working on those books. I've also started working on more books about the mythology of the Ryukyu Islands and also how their society worked. There's lots of stuff about the lives of women in the Ryukyu islands and stuff like that. And also punishment, crime and punishment.

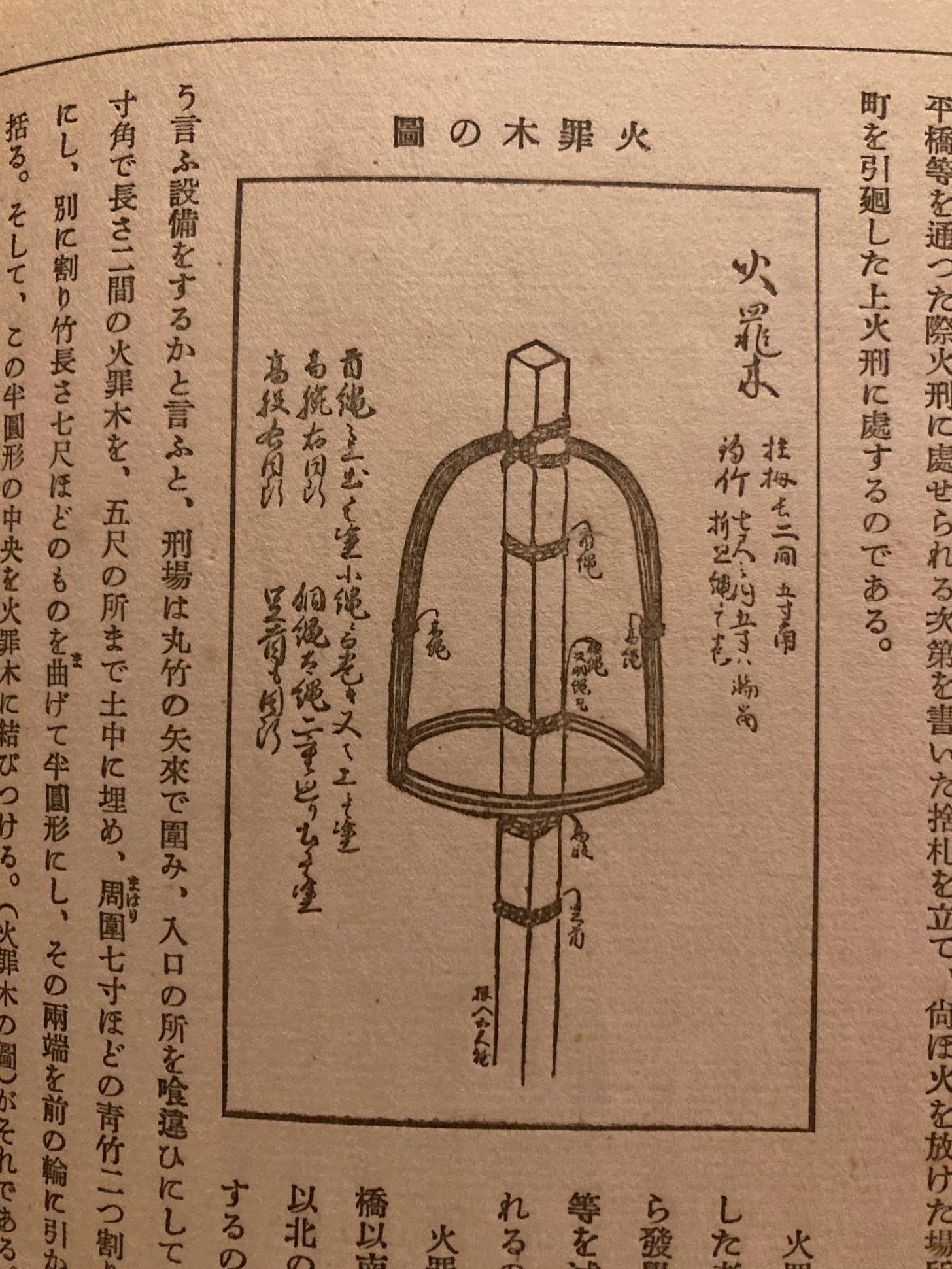

I just did a post recently where about crime and punishment regarding punishment for arson. So Edo was a city made of paper and wood, and so fire was a big problem. So if you committed arson, the punishment was they would burn you to death. And this mAinual, I found gives it step-by-step instructions on how to set up a fire to burn a person to death, how to tie 'em up, how to set up, how to bury the stake in the ground, how deep to bury it, and how to prepare it, how many people you need. And then at the very end, it includes a cost breakdown.

Leafbox:

No, I saw that on your Twitter feed, you had execution manual cost structures or something. And I thought that it's fascinating.

“死刑経済学 The economics of execution Executing a person convicted of arson (by burning them alive) required wood, bamboo, rope kindling and other materials costing a total of approximately 197 monme 匁 (738 grams/ 1.6 lbs of silver.) A monme of silver is 1,200¥ so 6000$”

Eric Shahan:

It's like, man, this is, it's not just some, yeah, just get some brush together and tie 'em up and light 'em on fire. It's like how many people you need to tie 'em up and where you should tie 'em up and make sure you cover the rope with mud and then tie some loose string around that and do this and that. And then at the end, it's just a total cost structure. Each of those punishments has the economics of execution aspect to it, how much it would cost to execute someone, or it actually has how much it costs to tattoo someone too. That's another project. I'd like to make it into a full book, the Economics of Execution and Punishment, but

Leafbox:

I'm sure you have Japanese friends. And what do they think about your interests? Are they kind like this is just Otaku interests or they don't even read Showa era stuff. They're like,

Eric Shahan:

No one reads this stuff. No one reads this stuff. When I tell 'em about it, they're just like, what? It's like, what? It's like, what is this? What is this? I'm like, yeah, nevermind. Don't worry about it. I don't even jujitsu. They don't really know. My average Japanese person doesn't really know what jujitsu is. So I do jujitsu in my martial arts, and we also do Ken Jitsu sword fighting, but if someone were to ask me, I'd just tell 'em, it's judo. Otherwise they just don't know what you're talking about. It's not something many people, it'd be kind of like if you did, I don't know, medieval fighting reenactment in America or Europe, he'll be like, you do what?

Leafbox:

Yeah, I guess they would just think you're weird. Yeah.

Eric Shahan:

So you just go like, oh, I do boxing. You're like, oh, okay, cool.

Leafbox:

Well, the thing that's interesting to me is that if Meshima or someone was alive today, I think you'd be talking to him. These are all kind of not right wing, but dissendt cultures, like sub underground Japanese things that the government interacts with both through law, and I mean, execution is powerful kind of governmental law. So it's just interesting to see that culture and how that even affects contemporary Japan. All those lineages are still affecting Japan.

Eric Shahan:

There's lots of information there that I think needs to be put together to help understand contemporary Japan, especially the crime and punishment aspect, because a lot of people discussed like, oh, Japan's very safe, and it was even very safe in the Eddo era, but you have to look at how they maintain that level of safety. So there were some pretty strict punishments for people that started a fire. I mean, admittedly, if you started a fire in Eddo, it could kill an awful lot of people. And some of the fires that erupted in Neto killed like tens of thousands of people. So they had some strict laws and the way they ran the society could be very strict at times. Definitely. And it's definitely worth having that information available to further your research.

Leafbox:

I saw you were following, I think the Tono Museum.

Eric Shahan:

Oh god, that museum man, I want to go there so bad. It looks so awesome.

Leafbox:

Yeah. Maybe for people who don't know that, I guess I would call it folk esoterica spells.

Eric Shahan:

Yeah, it's a whole exhibit on folk magic, and they have all these wonderful little bits of paper and dolls and just looking at you, what is this? It's some clay doll wrapped in twine with all kinds of symbols on it. You're like, holy heck, what is this?

Leafbox:

What's your, yeah, because they're introducing Sanskrit. And how are you working with texts that are just beyond modern comprehension? I'm just curious. How do you approach those?

Eric Shahan:

Well, some of those esoteric texts, they're just, they're at the, you can read them. They're actually not that hard to read, but it's like, what is this talking about? It's hard to, what is this? You can read all the words in a sentence, but you don't know what they mean kind of. If you're a person, an English learner, trying to read a book by Shakespeare, you're like, what is this all about? Is this a joke? So you have to, I try to find this for the esoteric books. I try to find the simplest possible book on it and then work back towards the more complex books. I found the complex books, they look amazing, but I just don't know what's going on. So for the JI book, I'm actually working with a guy from Hawaii who is very knowledgeable about Sanskrit characters. So he's helped me, directed me to what the meaning of these Sanskrit characters were. And so then I have to attach that meaning to how the Japanese are interpreting that character at that time, because these things can change according to the time and also the sect of Buddhism and stuff like that. So there's a lot of moving pieces.

Leafbox:

Eric, how is your translation work then? I mean, people think it's an individualistic, you're in your office by yourself, but how is this a team sport? I'm curious about that.

Eric Shahan:

Well, I try to keep the text as is. I don't add, I don't add anything. My opinion to the text though, and I try to clearly delineate what's opinion, if this is person's opinion or something in a footnote. At the same time, I don't want to overdo the footnote thing, so I do sometimes put the definition of terms inside the translation just to reduce the number of footnotes and increase the readability. For example, if they just make an off-handed mention of Oda Nobunaga , I type in Oda who was a warlord, was killed in the JI incident, and 1582, you kind. So I don't, but other than that, I try to respect what the person was trying to say at the time, especially since some of the books are basically research papers. So I really want to be sure that I as close as possible to what the guy's trying to talk about as humanly possible

Leafbox:

As a translator have you looked at any other, I mean the opposite direction English texts going into Japanese, and I'm curious how you think about that process, or if you're not even,

Eric Shahan:

I'm definitely, I think I'm really good at translating English or Japanese to English. I don't know if I'd be able to translate a book from English into Japanese very well. I think it would sound really strange, but yeah, I'm not interested in doing that.

Leafbox:

I know, but have you read any texts? I'm just curious how you as a reader, how you approach translations reading an

Eric Shahan:

English text and wonder. There's definitely books in English that I think would be interesting for Japanese people to read, but I don't think I have the capacity to translate from English into Japanese.

Leafbox:

Got it. Eric, I'm just curious, what's next on, I mean, you're working on the Kiji book still, and what other topics are you really kind of excited for? Right now?

Eric Shahan:

I'm really interested in this Maedo story because the guy he talks about, he's traveling all over the world, meeting all kinds of interesting people and having funny interactions. And this story right now is in 1908, and there's all these funny, interesting people, and he's having trouble working up the rules of the matches and stuff like that. The western wrestlers want to have these kind of rules, and he wants to have these kinds of rules. So there's all kinds of interesting interactions like that, funny people, funny situations, and it's stunning to think that all this happened before World War I, not World War ii, world War I, this is like, it's 1908, so I'm really interested to see how far this story goes and what happens once he starts heading over to South Central and South America. Also, my goal is to continue publishing those esoteric texts, and I'm sort of working back in time now from the ones that were the easiest to the ones that are more difficult and more esoteric, and what else is there? Yeah, I definitely like to continue with the Edo Manga series where it's the funny little stories published in the 17 hundreds that were read by Samurai and Townsfolk in Edra. So I really liked those a lot.

Leafbox:

And then how are you, the final question I have on your translations, do you work with native Japanese speakers on questions or how do you approach really?

Eric Shahan:

I don't really know. No, I basically work on my own. I don't have any people that are regularly ask questions about better Japanese. I actually have quite a few people that are quite well versed at Japanese and are also very knowledgeable about a topic. For example, I have a friend named Lance Gatling who's very knowledgeable about judo. He's involved with the kohan, and he is a fountain of knowledge about how Jiro got judo started and how he

Leafbox:

Spread it through the world.

Eric Shahan:

Correct. And he also had his fingers in a lot of pies. He was very involved in the government, so he was involved in all kinds of aspects of Japanese policy. So he's a source I use for judo. And then, like I said, I have a buddy in Hawaii named Gabrielle Rosa, who's very interested in Buddhism and Ji and Jisu. So I consult with him on items related to the Sanskrit characters.

Leafbox:

And is he a researcher or is a academic, or who is Gabrielle?

Eric Shahan:

He is a carpenter.

Leafbox:

Oh, okay. Wonderful.

Eric Shahan:

He's a carpenter researcher and he does some great research. He made, this guy is amazing. He made, there's a diagram of a collapsible boat that was in an old Nin Juzi mAinual, and he just made it. It's like unbelievable.

Leafbox:

Wild. And then one of my last questions, Eric, since you've been in Japan 20 years, how has your relationship to Japan changed? I mean, I feel like maybe it's an open-ended question. I'm just curious how you, now that you're going down this kind of deep world, what's your relationship to Japan changed? Contemporary or old or the west? I'm just interested in that.

Eric Shahan:

Well, everyone thinks they haven't really changed that much, but I hear from other people that I act a little bit differently from how I used to. I got asked the difficult question one time and I gave an evasive answer, and the guy just was like, man, you sound just like a Japanese person. So he was giving me grief. I was giving kind of a roundabout answer, and he wanted a direct answer. So I definitely still enjoy living in Japan, and I feel like there's a lot of things I still want to expand my knowledge on. So I'm very content, despite living a long time here. I'm very content with how things are going. And

Leafbox:

Then how does your relationship to the us, how has that changed? Do you visit often or do you not, or?

Eric Shahan:

Oh, yeah, once or twice a year. I go, actually. So yeah, I quite like it. It's definitely, you get a little bit of culture shock there, but I quite enjoy going to breweries and stuff like that. That's such a fun culture. And going to Mexican restaurants and stuff like that, they don't really have this here in Japan.

Leafbox:

Great. And then Eric, what's the best way for people to find your work and follow your output?

Eric Shahan:

Thanks for asking. Yeah, just go to amazon.com and type in Eric Shahan books and you'll see all kinds of stuff will come up. I think I'm up to 80 books now, but there's a lot of material there. And keep in mind that, so literally I do everything with those books from writing the description, making the covers, translating, formatting the book. So it's a one man operation. And all mistakes are my own. So if you see something and you get one of my books and you notice something that seems awry, just let me know and I'll fix it. And thank you personally for that.

Leafbox:

And then last question I have, Eric, your Twitter feed, what are you trying to do with that? Or is it just promotion or you have kind of an interesting feed? Just curious what

Eric Shahan:

Actually, I was just thinking about that the other day because my current research as well as some current events in Japan that I'm also interested in. So yeah, I guess what do you think that is?

Leafbox:

No, I think it's great. It's like a notebook of what you're thinking about and what you're working on, but it's very interesting and for people who are into esoterica and obscure things, it's really fun. So I appreciate it.

Eric Shahan:

It's literally notes in the sense that a lot of times the topic seems to jump around a lot, and that's because the book, I'm working on several books at the same time, so as I'm jumping around, I'm doing footnotes or looking up terms. So as I'm looking at those terms, those posts are just like a footnote I'm writing or some sort of term I had to look up or something like that, so.

Leafbox:

Nice. And then is there anything else you wanted to share, Eric, or,

Eric Shahan:

No, I appreciate you taking the time to interview me, and I definitely encourage people all over the world to try independent translating or independent publishing a try, especially with translating. A lot of countries are, what do you call it, digitizing their collections. Even the Vatican has their collection up and they have resources from all over the world. So if you find something interesting in one of those digital collections, translate it. Especially if you translate it into English and make it available, I think you'll find an audience.

Leafbox:

Yeah. What's so interesting about translation to me also is that it's the only time that you really, really read, right?

Eric Shahan:

Yes, yes.

Leafbox:

So yeah, I mean, that's really when you have to take the time sentence by sentence, word by word to try to, so it is an interesting reading experience. So I think translators are under-appreciated often, right?

Eric Shahan:

It's a good way to get, if you want to improve your language ability, you really have to drill in, read the same passage several times to get the meaning, and then once you get that sentence, you have to look at the one before and the one after. And how's all fit in to the writer's worldview and stuff like that. Probably my advice though on translating is don't set a goal of six pages a day or three pages a day or something like that. Just set aside a section of time every day. I'm going to work for an hour today or 25 minutes today. That's fine. Don't try to do, I'm going to do 10 pages a day. That's going to be really tough. That's going to be really tough.

Leafbox:

Got it. So how many hours do you usually work on this process? All day?

Eric Shahan:

It just depends on if it's a weekday after work, I might not really get that much done, or I might just read the passage or look up a couple of terms. A lot of times the book, oh, I'm working on a manga now, and he keeps referring to these old Chinese aphorisms, and I'm like, what? I had no idea what the heck he's talking about. He's patiently waiting to take revenge. This is a story from the 1800s. He's patiently waiting to take revenge, and he's like, I have to sleep on sticks and lick a gallbladder. What the heck does that mean, man? And this is a story of a Chinese king who was defeated in battle, and in order to remain humble, he slept on a bed of sticks and had a gallbladder that he would lick or eat every morning with the bitter taste of, which would remind him of defeat. So I have to now tie that into being patient about seeking revenge.

Leafbox:

Awesome. Well, I appreciate you sharing all this obscure topics with the world, and Eric, I really appreciate your time as well.

Eric Shahan:

No, thank you. It was fun.

Okay, have a nice day. Thanks so much. Bye.

Twitter: @ShinobuBooks

Instagram: @Shinobu Books